As a BBC documentary considers whether the Christian anti-porn crusader Mary Whitehouse was ahead of her time, Rev Peter Crumpler recalls his own conversation with the often mocked campaigner

Almost 50 years ago, a teenage would-be journalist was sent to interview one of the most controversial Christian figures of the 1970s.

That aspiring reporter was me. I was dispatched by Buzz magazine (predecessor to Premier Christianity) to interview anti-porn campaigner Mary Whitehouse.

Although Christians under 40 may not know her name (I recently mentioned her name in a sermon only to receive blank looks) Whitehouse was a high-profile figure from the mid-sixties until she retired in 1994. She was often parodied and mocked in the media for her campaigns against obscenity.

I recalled the interview, and dug out the cutting from my loft this weekend because the BBC was broadcasting a new radio programme, ‘Disgusted, Mary Whitehouse’ based on 30 years of newly-available diaries and letters. It has led some to a reassessment of her impact.

The programme’s presenter Samira Ahmed raises a key question: “Mary Whitehouse’s name became shorthand for anti-liberal prudery and censorship, but more than 20 years after her death, do her diaries reveal a woman who was ahead of her time in warning about the corrosive impact of internet pornography on society?”

The documentary reviews Mary Whitehouse’s years of protests and records how she persistently lobbied MPs and ministers to draft legislation.

Ahmed notes: “Her successes include the 1978 Protection of Children Act, which criminalised for the first time the making of indecent images of children, the 1981 Indecent Displays (Control) Act which controlled sex shops and the displays of pornographic material in newsagents, and the 1984 Video Recordings Act, to regulate the explosion in the sale of extreme content (so-called ‘video nasties’) in the new Wild West of home video cassette recorders.” She warned about technology getting out of control, long before the internet was born.

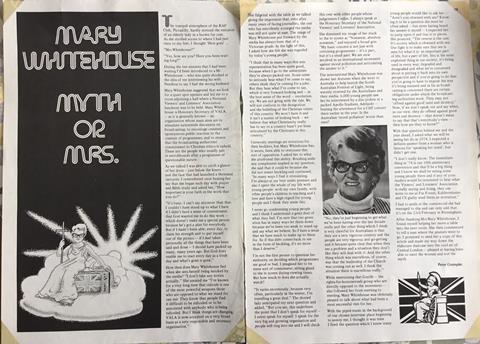

When I met Mary Whitehouse in the plush surroundings of the RAC Club in London’s Piccadilly, she was about to attend a meeting of the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, the lobbying group that she chaired and had around 150,000 members at its peak.

In the minutes before Mary Whitehouse arrived, I had been introduced to a Mr Whitehouse, who was shocked at the idea of my interviewing his wife. Needless, to say I had the wrong husband.

But there was no mistaking the actual Mary Whitehouse when she arrived, wearing a brown fur coat, and with a hand outstretched in welcome. I was seeing, I wrote, “the face that had launched a thousand cartoons.” Although I was painfully nervous to be meeting such a high-profile person with a fierce reputation, I found her warm and charming, and patient as I set up my cassette recorder.

Looking back, my questions were predictable. As a young, evangelical Christian, I wanted to know about her faith and how this motivated her. I asked about how she felt young people regarded her, and I asked whether she was obsessed with sex.

I don’t take any notice of mockery

About her faith, she told me: “It’s basic. I can’t say any more than that. I couldn’t have stood up to what I have if I didn’t have a sense of commitment that God wanted me to do this work. I don’t take any notice of mockery. I’ve known for a very long time that ridicule is one of the most powerful weapons those who are opposed to what we stand for can use.”

On young people, “When I go to universities they’re always packed out. Some come to seriously hear what I’ve come to say, others think they’re coming for a joke. But they hear what I’ve come to say, which is very forward-looking and – in the best sense of the word – revolutionary. We are not going with the tide.”

On an obsession with sex, “The reverse is the case. It’s society which is obsessed with sex. Sex is the most exploited thing in our society. It’s being used in every way, degraded and denigrated and what we’re concerned about is putting it back into its own perspective, and if you’re going to do that you’re going to have to expose the way it’s being misused.”

Many people saw Mary Whitehouse as a campaigner seeking to return Britain to ‘Victorian values.’ In fact, in many ways, she was warning about the increased sexualisation of society that the internet – then many years in the future – would bring. Today, she would be campaigning for increased protection for children on social media, and controls on how the internet makes obscene material easy to access.

As journalist Samira Ahmed concludes: “Although some of Mary Whitehouse’s religious beliefs were very out of step with modern Britain, she would see the impact of internet pornography on the young as exactly what she’d been warning against and support the current efforts to finally get it under control.”

Disgusted, Mary Whitehouse is available now on the BBC Radio 4 website