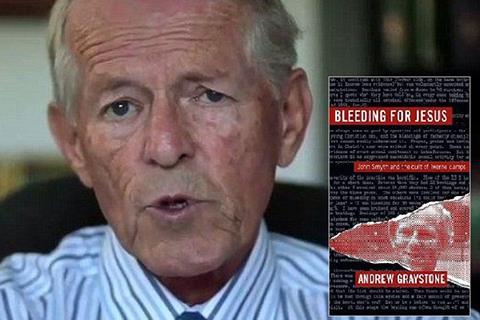

Andrew Graystone’s new book has been praised by Channel 4’s Cathy Newman for giving a "disturbing, devastating and damning account of abuser John Smyth.” But others are concerned that Bleeding for Jesus has unnecessarily outed some of Smyth’s victims. Theologian Rev Dr Ian Paul gives his view

Many people have told me that Bleeding for Jesus: John Smyth and the cult of the Iwerne Camps is essential reading, and I take this recommendation seriously for three reasons. First, I have known the author, Andrew Graystone, for some years, and engaged him to teach media and communications skills at the theological college where I taught. Secondly, as an evangelical of many years, I need to listen carefully to any well-founded critique of evangelical theology and practice. Thirdly, abuse and safeguarding is a critical issue for the church, and this book is an important exploration of one particular and poignant case.

Graystone’s book is a detailed account of the abuses perpetrated by John Smyth, who started life as a high-flying lawyer, working in prominent cases in the 1970s alongside the likes of Mary Whitehouse, but who then became heavily involved in the work of Iwerne Camps. These conservative evangelical vacation camps in Dorset, were found by Eric ‘Bash’ Nash after the Second World War, and targeted boys from public schools with the aim of converting future leaders of the nation to Christian faith.

The ethos of the camps would be seen by many as disciplined to the point of being authoritarian, and Graystone puts forward the case that they were rooted in an unhealthy emotional, psychological, and spiritual outlook. Within this authoritarian context, and with the lack of concern for transparency and accountable that marked all organisations until very recently, the camps offered a context for Smyth to indulge his abuse of boys in his charge, which involved both emotional coercive control as well as physical beatings.

Graystone has put his investigative and communication skills to work, and has produced an exhaustive and harrowing account of the abuse perpetrated by Smyth, who died in 2018 before he could be held to account for his abuse in England and also in Zimbabwe, where one 16-year-old died in mysterious circumstances on one of Smyth’s camps. The accounts of Smyth’s abuse of various individuals is relentless and forensic in its detail, and a picture emerges of a man who was pathologically obsessed with control and discipline.

That is enough to make the book very uncomfortable reading - but I felt uncomfortable for other reasons too. The first is the context that Graystone sets out in the early chapters, where he offers what I can only describe as a parody of evangelical theology and culture in the 1970s and 80s and later, a culture which he claims was sexually repressed and emotionally constrained, eschewing proper critical thinking. It was not a description I recognised.

The second theme is Graystone’s repeated claim that the spirit and ethos of Iwerne have ‘infected’ the Church of England in general, and evangelical Anglicans in particular. He makes this claim by mentioning the names of those who have led influential churches, and those who became bishops, including Nicky Gumbel at HTB and Justin Welby as Archbishop of Canterbury. But a relatively short list of names is repeated again and again (and at this point the book is rather repetitive), and there is no real exploration of the connection of these individuals to Iwerne and its theology. Graystone does note that people like David Watson, the evangelist, and John Stott, of All Souls’ Langham Place, were critical of aspects of Iwerne’s culture and those who embraced the charismatic movement were regarded as ‘heretics’ - yet for Graystone their guilt by association remains.

In reading the detailed accounts of Smyth’s abuse I also had questions about Graystone’s sources. He has clearly spent time with many of the survivors, and makes use of their first hand accounts. But how does he give us authoritative accounts of meetings between bishops at which he was not present, and their views of one another? This is where the book takes a worrying turn, as Graystone feels free to offer some extremely negative and personal assessment of key figures in the Church, including Justin Welby. I was not clear why such damning personal criticism was warranted when the book could have focused on the real failures of process in a much more objective way.

One of the key figures, Alasdair Paine, currently rector of the Round Church in Cambridge, was a victim of Smyth’s abuse, and collaborated with Graystone - but he has since complained at the misrepresentation and inaccuracy in Graystone’s account. In turn, Graystone accuses Paine of not doing enough, and so being the wrong kind of victim, who is now guilty of allowing Smyth’s abuse of both him and others to go unreported. Andrew Watson, the bishop of Guildford, is also tarred with the same brush - though a victim, now apparently guilty of allowing abuse having initially introduced others to Smyth. I wondered by what right Graystone felt able to out and then label victims in this way.

The conclusion was something of a theological mess. Graystone offers a critical assessment of the theology of Eric Nash and the camps - and such critical appraisal is surely necessary. But the issues are dealt with clumsily, so that Graystone ends up dismissing some theological themes - the universality of sin, the need for redemption and, of course, historical biblical teaching about the nature of marriage - which are pretty close to the core of orthodox Christian belief.

The legacy of abuse and safeguarding remains a messy quagmire in the Church of England, and as Jon Kurht has persuasively argued, what is needed is a disinterested commitment to truthfulness, for the sake of all, not least the victims. Although Graystone’s book rightly brings some unpleasant truths into the light of day, because of his other concerns, this is, alas, not what this book offers us.