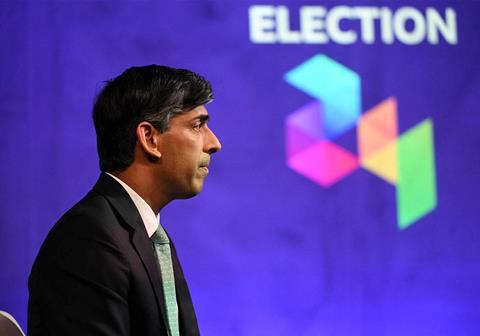

Rishi Sunak wants mercy for himself, but justice for others. He’s just like the rest of us, observes Natalie Williams

It is hard to find anyone who doesn’t think Prime Minister Rishi Sunak made a big mistake by leaving D-Day commemorations early last week. This week, he asked for forgiveness. The BBC reported that at an event in West Sussex on Monday morning, the PM said: “I just hope people can find it in their hearts to forgive me.”

The same morning, he posted on X:

If you're a criminal, the law should show you no mercy.

— Rishi Sunak (@RishiSunak) June 10, 2024

So it seems that Mr Sunak would like to receive mercy for himself, but he is not that keen on showing it to other people.

As much as hate to admit it, I am just the same. I tend to want justice for others, and mercy for myself. I suspect we are all a little bit like this, if we are honest.

To take a small example, I was recently caught speeding. The person delivering the speed awareness course I went to pointed out that all of us were technically criminals! In that moment, I didn’t want justice. I wanted mercy. I would have rather got away with it, or been let off any consequences.

But when someone hurts me, or someone I care about, I have a strong and pretty relentless desire for justice. I want the person to be punished, or at the very least to understand the harm they have caused and say sorry…And sometimes them saying sorry isn’t enough for me! I want them to prove it, somehow.

I am nowhere near as merciful as the father in Jesus’ parable about the prodigal son. If I had seen my wayward son walking home, I would have wanted a stern conversation with him. I would want to check that he understood what he had done wrong, and was genuinely contrite, and wouldn’t do it again. Then, and only then, I might welcome him home.

But the father in the story – who represents God – doesn’t even wait to hear the speech the son has been preparing. Before there’s even been an apology, he throws himself at his son, kissing him and embracing him with open arms.

My heart, and our society as a whole, are not like that. Our culture rushes to cancel those who have sinned. We seem to forget that we all make mistakes, often judging ourselves by our finest moments and others by their worst.

When I do something wrong, along with my apology I will offer you an explanation. I will usually defend myself by telling you that my intentions were good. But when someone else does something wrong – whether someone I know who hurts me personally, or a complete stranger who is in the public eye – I am prone to assuming they meant it. I meant well; they meant harm. My motives were good; theirs were not.

I don’t believe that the Prime Minister actually wants our society to be a place of “no mercy”. If he did, he wouldn’t have asked the public to forgive him. A culture without mercy would be one where there is no hope for those who do wrong, whether deliberately or accidentally. It would be a place where no mitigating circumstances were ever considered, and there was no hope of redemption.

I want to live in a society where there is always hope of mercy – where we know that we can be forgiven

Romans 1 features a long list of wicked deeds carried out by men and women, ending with “they have…no mercy” (Romans 1:31 NIV). Followers of Jesus need to hold out a better story than that. Justice at its best is full of mercy, because the desire of true justice is not condemnation with no let-up. It is repentance and rehabilitation.

Justice with no mercy doesn’t change anything. It might leave people languishing in guilt, but what good is that? I for one want to live in a society where there is always hope of mercy – where we know that we can be forgiven, we can be restored, we can be reconciled. And that’s the utter beauty of the good news: God sent his beloved son Jesus to die in our place so that, at the cross of Christ, we could find justice and mercy together in perfect harmony.

Mercy doesn’t mean sweeping sin under the carpet and pretending it didn’t happen. For mercy to really be mercy, it has to acknowledge that real harm has been done and that forgiveness is not deserved. That’s the very definition of mercy – it is undeserved love and kindness that we have no reason to expect, much less demand.

So though I can relate to the prime minister in wanting mercy for myself but not for others, where we differ is that I think our society needs more mercy, not less.

Natalie’s new book ’Tis Mercy All – The Power of Mercy in a Polarised World (SPCK) is published on 20 June

No comments yet