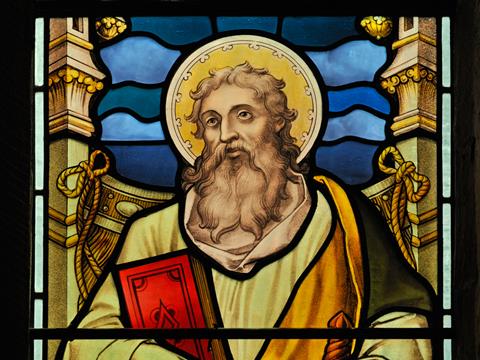

The feast of the conversion of St Paul marks one of the most powerful redemption stories in Christian history. But what can it teach us today? Samuel Tarr looks at what it really means to be converted to Christ

The feast day of the conversion of St Paul is being marked tomorrow. We all know the story of the Pharisee who persecuted the Church before being blinded by a great light as he travelled to Damascus. “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4) said a voice; “Who are you, Lord?” Saul asked in reply. “I am Jesus,” the voice said. Three days later, God sent Ananias to retore Saul’s sight; he baptised him and Saul immediately began preaching Christ.

Relating the incident in Galatians 1, Saul, now renamed Paul, writes that God “called me through his grace…that I might preach him among the Gentiles” (v15-16). It is in large part because Paul accepted this calling that people across the world have heard the saving message of Jesus Christ. It is through Paul’s voice that we hear God say: “Those who were not my people, I will call my people” (see Hosea 2:23, Romans 9:25).

What is conversion?

It is often claimed that Paul was not ‘converted’ from one religion to another, but rather ‘called’ to preach the Jewish God among the Gentiles. What changed was not Paul’s religion, but his vocation. As Swedish theologian, Rev Krister Stendhal, said: “the mission is the point.”

The whole of his life became a work of conversion, of turning towards Christ

In Philippians 3, Paul speaks of straining forward and forgetting what lies behind (v13); he did not focus on his past sins and failures. There is also no indication that he was conscious of something lacking in his religious life. Rather, we find a list of Jewish excellence: he claims he was a “Hebrew of Hebrews” (v5); “faultless” under the law.

And yet, Paul’s great zeal for his faith led him to persecute the Church. In meeting Christ, he discovered that where he thought he had been following God’s law perfectly he had, in fact, been opposing God’s purposes. Thus, Paul dramatically reconsidered both who he was, and who God was to him. One might argue that the question Paul asked: “Who are you, Lord?” is central to what we mean by conversion.

Changing grace

Paul’s identity and self-understanding changed dramatically. Undoubtedly, he remained committed to the one God of Israel, but his understanding expanded to a belief in “one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and through whom we live” (1 Corinthains 8:6).

Paul thought he had been following God’s law. He had, in fact, been opposing God’s purposes

From that point on, having met Christ, he considered all the successes of his former life “dung” in comparison (Philippians 3:8, KJV). In a crucial sense, the whole of his life became a work of conversion – of turning towards Christ, seeking to behold him more fully; continually and ever more deeply enquiring as to just who he is.

Knowledge and unity

For Paul, this was not an abstract theory, but a practical aim. The knowledge Paul speaks of comes through intimate contact and, ultimately, unity - through cultivating a life of prayer and contemplation. But beyond this, for Paul, “knowing” Christ comes from being united in his sufferings: “That I may know him, and the power of his resurrection, and the fellowship of his suffering, being conformed to his death” (v10).

“God chose to make known how great among the Gentiles are the riches of the glory of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory”, we read in Colossians 1:27.

Conversion, as we see on the road to Damascus, begins as an act of enquiry. But if our whole lives are to be an act of conversion - of being turned towards the Lord - then the Christian life must be one of continual enquiry.

One suspects that, in the end, we will see that all our life has been a question - or a series of questions - a continual probing of the things and people which constitute the objects of our attention and adoration. The life that continually asks: “Who are you, Lord?” is, perhaps, the only life that could possibly find a worthwhile answer.

No comments yet