Perhaps the former Archbishop of Canterbury intended to convey remorse and accountability in his conversation with Laura Kuenssberg. But that’s not how it’s been received, observes George Pitcher

Back in June 2011, I negotiated a guest editorship of the New Statesman for Dr Rowan Williams, then Archbishop of Canterbury. We commissioned coalition ministers such as Iain Duncan Smith and William Hague and a piece from Gordon Brown on youth unemployment.

Then Dr Williams wrote his leader. It was a reasoned and reasonable piece on the shifting tectonic plates of British politics, which in passing noted that “Government badly needs to hear just how much plain fear there is” around issues such as child poverty, access to education and sustainable infrastructure in poorer communities.

It was the line I lifted for the headline: “The government needs to know how afraid people are”. And I showed the page proof to a colleague who looked after the archbishop’s parliamentary affairs, a man whose judgment I much admire. I asked simply what would happen when we published.

He said the proverbial would hit the fan, Lambeth Palace would lose the government front bench and there would be real anger on the Conservative backbenches that the Archbishop had said something unsayable. Good, I replied, that’s what we’ll do then.

My friend was right. Angry and abusive letters were written, by many Conservative parliamentarians who clearly had not read the piece beyond a glance at the headline. Williams was ostracised by the Conservative Party.

Dr Williams wrote to me afterwards to say that it had been a more than worthwhile exercise and had achieved what we’d intended. We’d spoken truth to power, had given voice to “ordinary” people and spoken with a prophetic voice.

The point I want to make is that we knew what we were doing and why we were doing it. We knew what we wanted from it. We were ready for the quite predictable lines of attack and had answers to them. We had sparked a debate that we wanted.

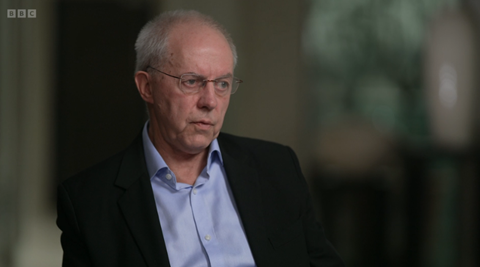

Compare and contrast that with Dr Williams’ successor last Sunday, which has been widely denounced as yet another exercise in self-exculpation, despite Welby’s repeated assertions that he is “deeply ashamed” and “sorry” that he “got it wrong” in failing to respond actively enough to church volunteer John Smyth’s serial child abuse, failings that led to Welby’s almost unprecedented resignation.

If Welby still has advisers, what were they and he thinking? The very first question anyone should have asked him as he considered going on the BBC is: What do you want to get out of this? We can only speculate in what his answer that might have been. He looked defeated.

A journalist friend who knows him a bit said he looked “deflated”, like he’d been punctured, slightly slouched in his sit, slack-paunched, only making eye contact with Kuenssberg when he had to. However much he repeated that it was all his fault, the impression given, intentionally or not, was “poor me”. Once again, he comes over as the victim, rather than focussing exclusively on those countless victims of Smyth.

Note that he is not, in the interview, wearing clericals and a pectoral cross of office, but an open-necked blue shirt and business suit. I don’t for a moment think he has any kind of messianic complex, but the impression nevertheless is extended of ecce uomo.

But, again, why? No one has demanded his public presence again. He could have slipped quietly into the obscurity of retirement. By his own admission, he had already made a truly dreadful valedictory speech in the House of Lords, in which he joked about the situation in which so many people had suffered through his professional neglect.

He could have used the interview to say what was wrong with the management structures of the Church and what needs to be done to put them right. But he didn’t. He just said that he “was overwhelmed”. Presumably that circumstance won’t be improved when a successor is appointed to his place.

There are times to invite censure and opprobrium from your critics, as the New Statesman venture of 14 years ago demonstrated. This wasn’t one of those times.

Whoever is doing the job I once did should have said softly but firmly: “You’ll get nothing out of this. Don’t do it.”

3 Readers' comments