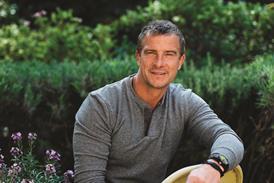

Dave Tomlinson, the author of How to be a Bad Christian, responds to Boris Johnson’s latest statement on faith

I have no problem with people getting divorced. I have married dozens of divorcees. I even counselled people to leave marriages for various reasons, and I abhor the judgmentalism which damns people to remain in miserable or even abusive relationships, or to live with guilt and shame for having left them. So, I have no issue with Boris Johnson’s marriage to Carrie Symonds – I wish them well in their life together.

But I find it nauseating that they could marry in the Catholic Church in circumstances where so many could not. And to my sometimes-reluctant Protestant mind, the loophole that Johnson’s earlier marriages were not valid, frankly, makes my blood boil. Yes, I understand all that ‘marriage is a sacrament’ stuff. But speaking as a committed sacramentalist myself, I really see it as convenient gobbledegook – which in the case of Marina Wheeler, Johnson’s second wife, discounts 25 years of marriage and four children on an ecclesiastical technicality. Rules, it seems, can be bent to absurdity for the rich and powerful.

But more than his marital status, what intrigues me is Boris Johnson’s religious standing. After a lifetime of showing not a scintilla of interest in religion, he appears to have undergone something of a personal revival: talking on Easter Sunday about the teachings of Jesus and his death and resurrection, advocating Christian ethics and ‘love thy neighbour’; and making it clear that ‘the foolish man hath said in his heart there is no God’ (presumably a message to atheist Kier Starmer!)

Johnson has just admitted last week to being a “very, very bad Christian”, who nevertheless believes that Christianity is a superb ethical system. “No disrespect to any other religions,” he says, “but Christianity makes a lot of sense to me.”

But what does “a very, very bad Christian” mean for Boris Johnson?

He advocates Christianity as a superb ethical system but demonstrates little or no commitment to following it

I co-opted the term in my book How to be a Bad Christian – and a Better Human Being, to reach out to the hoards of people who never go to church yet harbour genuine spiritual instincts and aspirations and try to mirror them in their daily lives. My definition of a ‘bad Christian’, therefore, is someone who probably cringes at organised religion, who has little time for creeds and doctrines and churchgoing, yet nevertheless attempts to live in the spirit of Christianity. And there are many people like this, who perhaps, without believing in Jesus, follow his way much better than many of us who claim to be his followers.

However, my sense is that it works the other way around for Boris Johnson: he advocates Christianity or the way of Jesus as a superb ethical system but demonstrates little or no commitment to following it, in either his personal life or in his politics.

My minimal expectation of a ‘bad Christian’ is a commitment to the ‘golden rule’ – “In everything do to others as you would have them do to you” – which isn’t just a central plank in Christian ethics but a fundamental component to being a decent person.

However, I don’t see much evidence of the golden rule in Boris Johnson. He is a serial philanderer who shows no evidence of acknowledging, let alone addressing the impact of this behaviour on others. He spoke of gay men as ‘tank-topped bumboys’, wrote that women in burkas choose to go around ‘looking like letter boxes’ or ‘a bank robber’, described black people as ‘piccaninnies’ with ‘watermelon smiles’, language for which he later apologised but claimed was taken out of context.

Public ethics is really the golden rule at work in wider society. And Boris Johnson’s government has made a habit of bending rules and ignoring advice, left, right and centre. But for me, its most reprehensible violation of the golden rule is the cutting of UK overseas aid that will undoubtedly lead to untold suffering, deprivation, and death to so many who rely on this money. I’d like to believe that the intervention of philanthropists like Bill Gates and others to help plug the UK gap in overseas aid with emergency funding will shame Johnson’s government into changing its mind. But I’m not holding my breath.

Boris Johnson once described his own faith as ”a bit like trying to get Virgin Radio when you’re driving through the Chilterns. It sort of comes and goes…Sometimes the signal is strong, and then sometimes it just vanishes. And then it comes back again.”

I completely understand the analogy. We may all have doubts and uncertainty, that’s normal. But you don’t need a PhD in faith to know that treating people how you’d like to be treated is the right way to go.