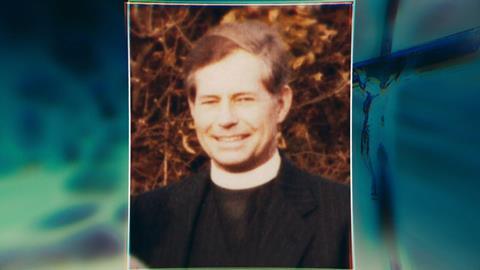

Rev David Fletcher, brother to Jonathan and named in the Makin report as being instrumental in the cover up of John Smythe’s abuse, has himself now been accused of abuse. Tim Wyatt explores what happened, and what needs to change in the conservative evangelical church world to ensure such horrors cannot occur again

Just yesterday, Cathy Newman from Channel 4 News announced she was about to break yet another safeguarding scandal in the CofE.

She tweeted: “Tonight we reveal that the Reverend David Fletcher - the man who instigated the cover-up of John Smyth’s barbaric abuses - HIMSELF allegedly abused multiple girls. Exclusive interviews with three courageous women tonight at 7.”

Who was David Fletcher?

David Fletcher, who died a few years ago, was a very significant figure. He led the Iwerne camp movement for decades, during the period John Smyth was chair of the trustees and brutally beating boys in his garden shed.

Fletcher was in loose charge of the group of leaders who found out about Smyth in 1982 and forced him out of the Iwerne movement but also decided not to tell the world what they knew. He was the author of what is perhaps the most notorious quote in the whole Makin report into Smyth, when he tried to explain why he had led the cover-up in the 1980s: “I thought it would do the work of God immense damage if this were public.”

In reality, as one of Fletcher’s alleged victims told Channel 4, he was perhaps more worried that his own abuse would also come to light.

There was a nexus of powerful, respected men who were hurting a lot of people behind closed doors

Later, Fletcher was rector of the conservative evangelical stalwart St Ebbe’s, Oxford, where he remained after retirement until his death. St Ebbe’s have said that they did not know of the allegations against him until the news broke. However, they did say that, in 2017 (by which point Fletcher was elderly, unwell and not in ministry) two women told St Ebbe’s he had been “inappropriately tactile” with them. These reports were passed on to the Oxford diocesan safeguarding team, but the statement does not say if anything further happened.

The Diocese of Oxford has confirmed that the latest allegations against Fletcher came in response to the publication of the Makin review and include claims of sexual abuse and coercive and controlling behaviour. The reports were passed on to the police and “recorded as a crime”.

What has he been accused of?

The Channel 4 report included interviews with three women, all of whom accused David Fletcher of sexual abuse. Jeni was just 13 when she was befriended by the Fletchers. She was adopted, and says their home was a refuge in her difficult childhood. However, as she grew older, David touched her inappropriately, tried to kiss her and, aged just 16, he forced her to skinny dip in their pool and sexually assaulted her.

Sisters Caroline and Ali also had difficult childhoods, and their mother was unwell for long stretches of time. They were just eight and nine when they recall David kissing them with tongues. He exposed himself to them, sat them on his lap and ran his hands under their clothes.

All three kept their abuse secret for more than 50 years, saying they were scared of David and did not feel they would be believed. But when the Makin report was published, Caroline and Ali tracked Jeni down and all three decided to go public.

Behind closed doors

Fletcher is also the brother of Jonathan Fletcher, who was vicar at another influential church, Emmanuel Wimbledon. Jonathan is currently awaiting trial on charges of indecent assault and grievous bodily harm. During a pre-trial hearing in August he entered a plea of ‘not guilty’.

At this point, we can safely say there was a nexus of powerful, respected conservative evangelical Anglican men in the 1980s who were hurting a lot of people behind closed doors. These men knew each other, shared ministry together and preached in each other’s churches, camps and missions. They were all seen as honoured leaders and sound Bible teachers. Their ministries inspired hundreds of others; their methods were widely copied. And they were abusers.

Aged just 16, Fletcher forced her to skinny dip in their pool and sexually assaulted her

We don’t know yet to what extent David Fletcher and Smyth were aware of each other’s actions at the time, although David Fletcher does appear in the Makin report and he was central in ensuring news about Smyth’s beatings did not become public. What is also clear is that Smyth and Fletcher (and let’s be honest, there were probably more we don’t yet know about) were only exposed after decades of abuse, in part because they carried such authority and power in the small but tight-knit conservative evangelical Anglican world.

Confronting the culture

Other traditions have also been rocked by their own abuse scandals - but there will no doubt be particular weaknesses endemic to conservative evangelicalism which make it harder for churches in that stream of Christianity to recognise and root out abuse

What is encouraging is that work to try and reset that culture is already underway. The Christian safeguarding consultancy ThirtyOne:Eight has published wider reflection on conservative evangelical culture beyond Emmanuel Wimbledon. They also did something similar for the Titus Trust, which had taken over running the Iwerne Camps.

Then, the Makin review included an appendix from a clinical psychologist who tried to investigate what was driving Smyth. She included a summary of her thoughts on how the wider culture of conservative evangelicalism may have contributed to the scandal: A hierarchical structure, authoritarian leadership, emphasis on obedience and loyalty, Muscular Christianity, godliness through self-sacrifice and hard work, boarding school culture, intense mentoring, patriarchy.

For those conservative evangelical churches prepared to ask difficult questions of themselves (including St Ebbe’s, which said it had already been reviewing governance and culture in response to the Fletcher and Smyth scandals), this has been food for thought.

It has also prompted work by the Church of England Evangelical Council (CEEC), who have created a project called In Lament, which has produced liturgies and resources to help evangelical churches think through their collective failures in the light of recent scandals. It includes a booklet to help churches interrogate their own culture and identify where it might be leaving people unsafe.

If you’d asked me to guess what the response would be from conservative evangelicalism to the cavalcade of scandals, I would have presumed a prickly defensiveness. Or at best a wariness of outsiders poking around in their business and presuming to tell them where they have gone astray. But instead there has been considerable openness, at least by some, to asking difficult questions and being challenged to change.

The proof of the pudding will be what meaningful shifts in culture occur, and whether any of this makes it harder for the next generation of Fletchers and Smyths to get embedded in the Church. But at least we are now having a conversation that is deeper than the “one bad apple” defence.

2 Readers' comments