Giorgia Meloni is set to become Italy’s first female prime minister, but don’t be fooled by her talk of God, says Christopher Lamb. She’s one of a growing number of populist politicians using the language of faith to further their political aims

Arriving just in time to deliver a speech at the 2019 World Congress of Families – a coalition founded by the Christian Right in America – Giorgia Meloni explained why she had been held up. “I was doing the ironing,” she joked, a little out of breath after walking swiftly up to the lectern. “Then I found ten minutes to come and talk about politics with you.”

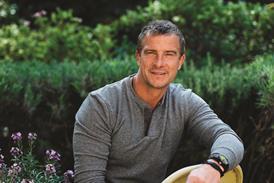

Her self-deprecating remarks disguised the steely political will of a woman who is set to become Italy’s first female prime minister. They also point to how she has deftly become the face of Italy’s far-right through appropriating language and narratives that appeal to Christians.

Who is Meloni?

Meloni, a 45-year-old mother of one, has defied the odds to triumph in Italy’s traditionally male-dominated political culture seeing off more prominent right-wing leaders such as Matteo Salvini, the head of the Northern League, and former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. Her election victory means Italy will have its first far-right-led government since World War II.

Born and raised in Rome, Meloni has been in politics for decades. As a teenager, she joined the youth wing of the Italian Social Movement, the party founded in 1946 by supporters of the former fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. After a period in local politics, Meloni was elected to the Italian parliament as a member of the National Alliance Party, a successor to the Social Movement but with a more moderate stance.

Berlusconi appointed her Minister for Youth at the age of 31, and four years later, she set up the Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) Party, which won 26 per cent of the vote in this year’s elections. The party’s name is taken from a line in the Italian national anthem.

The rise of the far right

The Brothers of Italy won just 4.5 per cent of the vote in 2018, but a mere four years later their popularity is soaring, as Italians have increasingly rejected mainstream parties.

Italy’s politics is famously volatile, with 69 different governments since 1945, and high youth unemployment and inequality between the north and south. The country has been on the front line of the refugee crisis, providing an easy target for politicians looking for scapegoats to blame for the country’s problems.

The far-right has been on the rise for years after the Berlusconi administration normalised a number of its parties. Meanwhile the left has been divided and the populist, anti-establishment Five Star movement failed to deliver.

Although Meloni has adopted a moderate stance, seeking to disavow the neo-fascist roots of her party, she has taken a hard line approach to immigration, calling for a naval blockade to stop refugees arriving in Italy from Libya. She has also accused the Hungarian-born financier, George Soros, of financing mass immigration and wanting “ethnic substitution”. Soros, who is Jewish, is a bogeyman for the hard right.

The language of faith

Meloni uses religious language when appealing to an electorate for whom Catholicism is part of its DNA (although the practise of the faith has waned). “We will defend God, country and family,” she declared to an audience in Verona.

On another occasion, speaking in front of the Basilica of St John Lateran, the Pope’s cathedral church, Meloni shouted: “I am Giorgia, I am a woman, I am a mother, I am a Christian.”

Italy’s new political leader is part of a trend of nationalist populist politicians who use Christian iconography and symbols to further their political aims. The most prominent example being former president Donald Trump who held up a Bible in front of St John’s Episcopal Church in Washington DC after protestors were forcibly cleared away from the area.

In Italy, Matteo Salvini, the country’s former interior minister, began to kiss the crucifix during political meetings and once brandished his rosary beads at an election rally while claiming the Virgin Mary was willing him to victory.

Salvini is a critic of Pope Francis and was seen wearing a t-shirt which said: “Benedict is my Pope”, referring to the Pope Emeritus, Benedict XVI. Salvini is expected to have a prominent position in a Meloni-led coalition government, and his harsh security laws against migrants and refugees are likely to be revived.

Catholicism without Christianity

In truth, these politicians are presenting an ideological form of Catholicism without Christianity, where the symbols and language of the faith are emptied of their meaning. The Italian journalist and author Iacopo Scaramuzzi has argued that the use of Christian iconography is an attempt by populist nationalists to give a “soul” to their politics and that most do not hold genuine religious convictions. Some argue that the strategy is straight out of the playbook of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The politics of Meloni run counter to a Pope who has been unafraid to face down nationalist populism throughout his pontificate. His welcoming stance towards migrants, dialogue with other faiths and concern for the environment are all rooted in a pontificate that seeks to implement gospel-based reform of the Church.

When it comes to migrants, Francis’ strategy can be summed up in Matthew 25:35: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” And although he has not changed any Church teaching on marriage, the family or abortion, Francis refuses to engage in the culture wars.

By contrast, Meloni has presented herself as a defender of traditional values by taking a strong stance against LGBT rights. She has already sought out those cardinals who oppose the direction of the Francis pontificate, and recently held a meeting with Cardinal Robert Sarah, the Holy See’s former liturgy prefect, who claims it is a “false exegesis” to use the scriptures to promote migration.

Don’t expect Francis to be cowed. He survived the far-right military dictatorship in Argentina in the late 1970s and 80s. As the Meloni-led government is formed in Italy, standby for Church and state clashes.

No comments yet