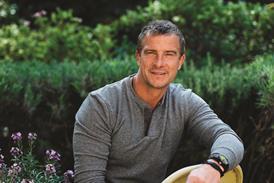

Joe Rigney has authored a much-discussed new book entitled The Sin of Empathy. He defends his thesis to Sam Hailes

If I were to list the fifty biggest problems facing the Church today, I don’t think ‘too much empathy’ would make the cut.

But Idaho-based pastor Joe Rigney disagrees. His provocative new book is entitled The Sin of Empathy (Canon Press) and claims empathy is “the greatest rhetorical tool of manipulation in the 21st century”.

Needless to say, the book has already generated plenty of online discussion. Can empathy really be sinful? I spoke to him to find out more.

Why do you believe empathy is a sin?

Because like all good things, the emotional response that we have to people in suffering ([whether you call it] empathy, compassion, pity, sympathy) - when it’s good, it’s good. And when it goes wrong, it goes really wrong.

Virtues typically go wrong in one of two directions, either deficiency or an excess. A deficiency of courage is cowardice, but an excess of courage is recklessness.

The defect of compassion would be apathy, callousness or heartlessness. But there is such a thing as an excess of compassion. You say, “How could you be too compassionate?” Well, if you’re overwhelmed by your feelings and you lose touch with what is true and what is good, if you lose touch with Christ, you have an excess of that emotion that sweeps you off your feet and can be very destructive.

Can you give me an example of where an excess of empathy would be destructive?

If someone throws a pity party, starts to sulk, and then we capitulate and give in then we’re coddling, enabling and indulging them. We’d be focused more on their short-term feelings rather than their long-term good.

Another, more political example is the way the trans movement has weaponised society’s compassion. “Here’s people who feel themselves to be in the wrong body. They are very distressed by this mismatch between their biology and their felt sense of [identity], and we need to do whatever we can to enable them to align those, including surgeries.” When we tell the parent who has a boy who thinks he’s a girl, “would you rather have a dead son or a live daughter?” that’s a twisting of compassion. When asked, “Do you want to avoid your child [taking their own life]?” then to give in at that moment feels compassionate. You’re trying to keep them from being harmed in some way, but in doing so, you’re actually causing harm, because they’re going to take the puberty blockers or be castrated. That would be a more extreme political example.

The Church has wrestled with needing to give people the truth (sometimes called being prophetic) while also dealing with the reality and messiness of life (sometimes called being pastoral). Both approaches are needed. Is your concern that the good, pastoral desire to be compassionate and empathetic is going wrong when it’s no longer underpinned with the truth?

That’s exactly right. I’ll give you two biblical examples.

Think about the story of Job. All of his property is gone, and his kids have been killed. His wife comes to him and says, “Curse God and die!” This is a mother who has just lost 10 children. It’s the most horrific scenario you can possibly imagine, and she’s angry at God because of it.

In her distress, in her grief, she wants to curse God. Should Job out of empathy join her in her blasphemy? I think all of us recognise that no, that would be a very bad idea. But he could have very easily indulged her.

I sometimes say that the most empathetic leader in the Bible is Aaron at the golden calf. Here you have a distressed people, and Moses has been God’s man on the ground - but he’s gone now. He’s up on the mountain somewhere. So the people are distressed. In today’s language we might say they’ve been traumatised. They come to Aaron, and say, “We don’t know what happened to Moses. Give us gods who will go before us. We feel scared and we want gods.” Aaron sees this distressed and agitated people and finds their agitation unbearable and therefore goes along with it [and the golden calf is made, which the Israelites worship]. He does the unthinkable. He actually loses touch with the moral law that God had just given to them. I think that’s another example of the way that intense emotions from people in distress can lead us to do things that are sinful, destructive and harmful.

Aren’t you reading into the text something that isn’t there. Exodus 32 doesn’t say it was too much empathy with the people that led to Aaron’s sin. Wasn’t it just his own pride and people pleasing that was to blame?

I think that in practice, all of these things get jumbled together. The bottom line of my project is feelings are good, but really powerful and very dangerous, and therefore need to be anchored to something sturdy. As CS Lewis put it, “Mercy, detached from justice, grows unmerciful.”

When do you think empathy has been a problem in local, pastoral settings?

When you have someone come into your office alleging, “I’ve been abused.” Obviously this is a serious thing, but what are you supposed to do in that moment? For a time, at least, the counsel from big ministries and large Christian groups was, “believe all women” Why? Because compassion demands that you believe.

But that wasn’t only about compassion. Isn’t the truth that statistically, while false accusations happen, they are so rare, that it’s much safer to start from a position of believing the person reporting abuse? And when women have been disbelieved, abusers have got away with crimes…

I think that that was the claim. False accusations may be relatively rare, but even at a pastoral, local church level, frequently, what happens is exaggerations. I’m not saying “don’t have compassion”. I’m saying “make sure that your compassion is anchored” - so if someone alleges something, I want to be able to say, “Hey, this is really serious. If the claim is potentially criminal, then we’re going to call the police and have them help sort it out.” But at a pastoral level, there needs to be a willingness to say, “I need to hear both sides. You’re claiming this. I need to hear what your husband said, or what this other person said.”

I recall one scenario I’ve been in where congregants were accusing an elder of being disqualified from eldership because he was abusive. They said, “he’s prone to fits of anger and rage.” I said, “that sounds very serious. Could you give us an example?” The example was a previous congregational meeting where the elder had spoken against something these people were in favour of. He calmly and clearly said, “No, you’re wrong” to some people, but that was then interpreted as “fits of anger and rage.” In that circumstance, what empathy demands is, “this is the person who’s claiming to be the victim. I therefore need to give total credence to what they say. I need to affirm and validate and endorse and give no sense of question, no challenge, no questions, no withholding of judgment. I have to go all in. I have to jump in with both feet in order to validate their concerns.” But if the elders had done that in that scenario, they would have joined in with false accusations against a godly man out of empathy and compassion for alleged victims.

Hebrews 4:15 says of Jesus “We do not have a high priest who is unable to empathise with our weaknesses”. If Jesus was empathetic, then surely Christians should be too?

I actually think this is a really good example of what I’m talking about, because yes Christ is described as a sympathetic high priest, but that verse immediately goes on to say he was tempted in every way, as we are, yet without sin.

The “yet without sin” is important. His compassion did not lead him to abandon the Lord, to fail to trust his father, even in circumstances where he might have done so. He’s a great example, I think, of anchored compassion.

When a lot of people look at the American evangelical church, and especially those like yourself who espouse Reformed or Calvinist theology, they see a lot of head knowledge and emphasis on doctrine, Bible study etc. But God created us with hearts and emotions too. They’d say we need to encourage empathy, compassion and emotion. You’re in part of the Church which often lacks those things.

I think that’s a misreading of the American church context. I think that Western civilization is a whole is just flooded with emotions.

I’m not talking about the entire American church. The perception is that the more Calvinist or Reformed parts of the US Church are very head-orientated and neglect the heart or the emotions. Aren’t you from a part of the church which needs to demonstrate more empathy, not less?

We absolutely want head and heart together. But especially in recent years, there’s been an appeal to heart in order to circumvent more moral, rational concerns.

So to check whether your heart or emotions are leading me to do this – is something that I think even the Reformed world has succumbed to. What we now call wokeness, was able to penetrate fairly far into even reformed evangelical churches precisely because it circumvented rational discussion.

By releasing a book called The Sin of Empathy, you’re opening yourself up to criticism that you must be a very uncaring, unsympathetic kind of person. Are you aware of that?

Absolutely. And the provocative title is intentional.

It is designed to provoke thought. Some people say, “I’ve never thought of empathy being a sin.” And I say, “Well, have you ever thought of anger being a sin?” They’re both passions. There are good and bad versions. All this provokes thought and people have to kind of wrestle it to the ground.

I don’t mind. I’m willing to be misunderstood. Think about how many times Jesus said things that resulted in him being misunderstood and false accusations against him. He was willing to take the risk, for example, spending time with sinners, knowing he would be called a drunkard.

Are you the sort of person that doesn’t mind criticism? It doesn’t bother you.

Yeah. I would say I don’t mind if people understand and they hate it. That’s fine. It’s when I feel like people are misunderstanding it and reacting that I get a little frustrated.

The Sin of Empathy by Joe Rigby (Canon Press) is out now

4 Readers' comments