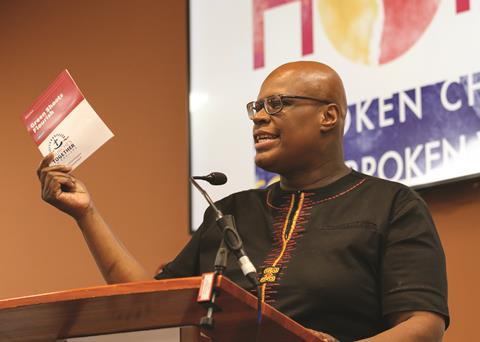

He prayed for King Charles at the coronation and has been called a “Christian man of influence”, but Bishop Mike Royal is far more interested in how the Church works together for the good of society than how others see him

Bishop Mike Royal has a CV that is just a little bit impressive. A result, perhaps, of his parents’ high aspirations – and definitely of their support and encouragement. Despite being “easily distracted” at school, Royal has a degree in urban planning and a Masters in Black theology. He’s been a youth worker, church leader, street pastor, mental health chaplain and the joint CEO of Cinnamon Network, a charity that helps churches to run community initiatives.

The deputy headmaster’s son is keenly aware of the advantage that his settled home life afforded him – and how many others are far less fortunate. It’s what drove him to work with kids at risk of school exclusion. That work became a national charity, Transforming Lives for Good (TLG), of which Royal was a founding trustee and, later, it’s national director. His own church still runs two alternative educational provision schools, of which his wife is the head teacher and he is a governor. When we speak, his passion for education, and improving the life chances of those most disaffected, is clear.

Earlier this year, Royal was listed in Keep the Faith magazine’s ‘Christian men of influence’ shortly after taking part in the coronation of King Charles III. It was, of course, “an honour”, he says. But, more importantly, it was a significant moment of Church history. In 1953, when Queen Elizabeth II was crowned, Catholics were not permitted to attend Protestant church services, so then-papal representative, Cardinal Bernard Griffin, sat outside Westminster Abbey. Seventy years later, Bishop Mike joined leaders from across the denominations – including Cardinal Vincent Nichols – in blessing King Charles.

Today, Royal is secretary general of Churches Together in England (it’s just like being the CEO, he tells me). Both he, and his organisation, take unity very seriously. Bringing together 52 denominations (“soon to be 54”), to enable “a deeper understanding of each other’s traditions, and encouraging them to work together for the common good” is a challenge both difficult and timely. With so many issues threatening to divide Christians today, the unity displayed at the coronation – even if only ceremonial – showed “how far we’ve come” in developing a truly ecumenical Church in the UK, says Royal. It’s vital, he says, if we want to reach our communities for Christ.

Did you grow up in a Christian home?

My parents were first-generation Windrush; they very powerfully met Jesus in 1960, around the time they got married. So, by the time I came along, they were quite mature in their faith.

We went to a classic Pentecostal church, but I was part of a Scout group, so I would go to an Anglican church once a month for parade. That was my first ecumenical experience! Perhaps my love of liturgy, and of the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Orthodox traditions, was sown during those years. My wife always says to me: “You’re a secret Anglican, really.”

I came to faith at 14 at a conference in Wales. I just knew my life was going in the wrong direction and I needed Jesus. I came forward and knelt down – 31 July 1982. I can put a very specific date on when I found faith for myself, and wasn’t just piggybacking on my parents’ faith.

Why are you so passionate about churches working together?

I take the words of Jesus in John 17:21 seriously: “that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you”. We should take that statement as seriously as we take the Ten Commandments and the Great Commission. It is a sign of the Church’s maturity. The challenge comes, of course, when you are seeking to keep unity even when there’s profound disagreement.

A very helpful tool is receptive ecumenism. You approach one another in dialogue, and come with a sense of lack, a desire to learn from one another and be enriched by one another – not necessarily to change your view but for a deeper understanding. It’s possible to do that and also hold a firm position in your own mind or tradition. Mature leaders are able to do that.

There’s a longing for another move of God in the UK. What do you think we need to do to see that happen?

The Church is never better than when it’s working together around social action and social justice. That gives it great credibility.

When the Church is a positive presence, people are attracted by it. If people find a loving community who accepts them, helps them with their mental health, offers friendship and support, people will be drawn to believe as well. At their own pace, in an appropriate manner, but it happens.

Lots of politicians would like to put the pandemic behind them, but the mental health fallout is huge

Most churches can unite around the foodbank, or rally around a Street Pastors’ team. Going back to John 17, Jesus says that unity is a sign that God loves the world [see v23]. If people see the Church loves the world, they will be drawn to it. And then renewal is much more likely.

Growing up, your parents’ expectations of you were much higher than your school’s. Why was that?

That first generation of Jamaican people who came to the UK had high expectations of themselves and their families. From a very young age, I remember my parents saying: “Mike, you’re gonna have to work twice as hard to get where you want to get to, because we’re living in a society where there is prejudice, racism and barriers.” [Their support] is a significant part of why I am where I am today.

Those were the seeds for the establishment of TLG as a charity – rolling out alternative education provision for children who didn’t have the opportunity or encouragement that I had in my home life.

Victor Hugo said: “He who opens a school door, closes a prison.” So many children who are excluded from school end up being known to the police, social services and, if there isn’t an intervention, end up in prison or deceased.

Tell us how you got involved in that work.

When I was national youth director with the Apostolic Church UK, I was the guest speaker at a conference in Denmark. One of the Kansas City Prophets pointed me out. I wasn’t sure whether it was because he heard from the Lord or because I was one of the few Black faces surrounded by all these blond-haired, blue-eyed Danish people! But once he spoke, I knew it was from the Lord. He said: “I see thousands upon thousands of young people.” At that time, TLG was just some youth work being run down the road. I never knew that, as the charity took shape, it would be the fulfilment of that prophecy.

What are the biggest challenges facing young people today?

A lot of children are facing poverty. Some things that people take for granted, others haven’t got. For instance, space to do your homework. Then there’s poverty of aspiration: many parents had a bad experience of school, so struggle to guide their children through education. To be honest, [many children] just need really good support, and those are issues in inner-city, rural and suburban areas.

We have to be very careful of media stereotypes that say knife crime is a Black issue. It’s not. It happens in the Asian community; it happens in the white community. Knife crime is as big a problem in small towns as urban areas. Until we deal with it as a public health issue, and not just a criminal issue, it will continue to blight our communities and destroy the lives of families and young people.

You’re currently a school governor. What challenges are schools facing right now?

Our church runs two alternative educational provision schools. It’s a beautiful thing, but also has its challenges. Post-pandemic, children are struggling with their mental health. The isolation had a huge impact; it happened at a critical moment in so many children’s lives. Lots of politicians and decision-makers would like to just put the pandemic behind them, or focus on the economic fallout, but the mental health fallout is huge, and we will be living with that for some time. I don’t think it has fully unfolded yet.

You could quite easily feel overwhelmed by that or, if you’re more optimistic, see it as a great opportunity for the Church. What would be your view?

I always reflect on the life and ministry of Teresa of Calcutta, who was surrounded by needs but never allowed herself to be overwhelmed. The key thing is asking: What are people experiencing? What is God doing? And how do we play our part? These are questions we need to keep asking, and avoid a messianic complex that says we’re here to save the world. Jesus is the saviour of the world. He chooses to use his Church as his hands and feet.

The Church is never better than when it’s working together

Is there anything in particular that you think God is doing at the moment?

God is shaking up what Church looks like. I think there’s a big question mark over some of the old models with lots of programmes. Churches need to be much more focused because volunteers have less time now. A lot of people retired during and immediately after the pandemic. Many churches still have not returned to their pre-Covid numbers.

I hear lots of leaders saying: “It’s not all about Sunday now.” Some churches meet every other week, and meet in homes in-between. There’s lots of soul-searching being done around how the Church stays relevant and sustainable. That can be a good thing.

It’s been wonderful to see the Church step up and work together again around things like the warm welcome campaign, foodbanks, etc. The one thing I would say, though, is that we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to share the reason why: because Jesus loves us, and he loves the world too. That shouldn’t be lost. It needs to be done in an appropriate way – we should not be doing social action with strings attached – but people ask: “What motivates a Street Pastor to be on the street at one o’clock in the morning?” People want to know: “Are you crazy? Why are you out here for free?” Those are moments where a conversation can open.

It’s good to hear you say that, because often there’s a divide between those who are committed to social action, and those who say: “We just need to preach the gospel.”

The Bible says go into all the world and preach the gospel, and I am with you always to the end of the earth [see Matthew 28:19-20]. And in James, it says don’t have someone sitting in your midst and tell them to be warm and fed, and not provide practically for their needs [see James 2:16]. It’s word and deed together; it will always be. Anyone who says anything else is not taking on board the whole counsel of God.

You’ve held many different positions of leadership. What are the biggest challenges you’ve faced?

The biggest challenges generally involve people or money. Anyone who’s been in charitable work will know there are moments when funds are short, and you have to make difficult decisions. In all the charities I’ve been in, there has been experience of that. And, of course, people – whether that be moral failure, or just disagreement.

There is too much cult of personality in the Church

Moral failure is such a massive problem right now, and Christian celebrity culture has been much critiqued. How do we create a healthy leadership culture?

There is too much cult of personality in the Church. We’d do well to walk together in healthy respect, and in an openness and vulnerability that allows us to call out particular behaviour when we see it. Too often, stuff gets put up with. It’s always tough to call out abuse of any kind, but it’s really important that we do it. Over time, that damage just gets deeper and deeper.

Leadership development needs to be built into our seminaries, so that leadership formation is really focused on. We need to create a much more reflective culture, with people reflecting on their own leadership, and where there’s an opportunity for others to feedback, whether positive or negative. Where that doesn’t happen, you end up on the slippery slope.

What do you think the Church will look like in 2033?

My prayer would be for the Church to be growing and making a genuine difference in local communities. When push comes to shove, it is about impact on people’s lives. Whether it be in Pakistan, Ghana or here in the UK, the best of the Church is seen when people open up the doors – metaphorically and literally – and embrace those who want to come in, or who have needs that we can meet. For me, the more of that, the better.

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on Saturday

23 September or download ‘The Profile’ podcast premierchristianity.com/theprofile

No comments yet