84 per cent of Britons say that you need to be a 'good person’ in order to reach heaven. But how good do we need to be? Kristi Mair shares her perspective

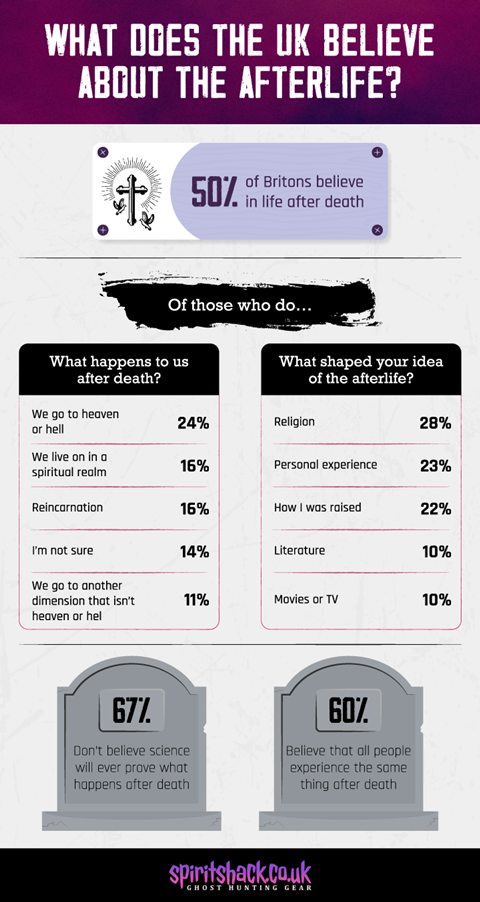

A recent survey by SpiritShack has revealed that half of Britons believe in an afterlife.

While reading the results I was immediately reminded of a conversation between Charlotte Brontë’s young Jane Eyre and the loathsome supervisor of Lowood school, Mr Brocklehurst:

“No sight so sad as that of a naughty child,” he began, “especially a naughty little girl. Do you know where the wicked go after death?”

“They go to hell,” was my ready and orthodox answer.

“And what is hell? Can you tell me that?”

“A pit full of fire.”

“And should you like to fall into that pit, and to be burning there for ever?”

“No, sir.”

“What must you do to avoid it?”

I deliberated a moment: my answer, when it did come was objectionable: “I must keep in good health and not die.”

Along with Mr Brocklehurst, 84 per cent of Britons who believe in heaven say that in order to get there one needs to 'live a good life and be a good person'. No naughty little girls allowed.

The irony of Mr Brocklehurst’s diagnosis, however, is not lost. Here, a detestable, hypocritical man has the audacity to accuse innocent Jane of grave misconduct warranting the very fires of hell itself. We need not look far for similar examples on the world’s stage today. It is in the face of such unjust behaviour that one rightly recognises that good behaviour should be rewarded and evil behaviour should be punished.

Is anybody good enough?

Is anybody good enough to enter heaven? Where do we draw the line between ‘good enough’ behaviour and ‘not good enough’ behaviour? And, more to point, if God does exist, where might he draw the line?

For a morally good God to exist, the standard could not be less than moral perfection. The bar is so high that it sits beyond all of us. God does not set the moral standard so high out of capriciousness, but because anything less would diminish his own goodness, and goodness itself.

The Russian novelist and political dissident, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, spent eight years in the Gulag followed by internal exile. In his book, The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn comes to this staggering conclusion: "If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

The survey respondents are right, one is required to be a good person and to live a good life in order to go to heaven; but, the reality is that none us is able. When placed next to such moral perfection, the Bible says that even our best deeds are nothing but filthy rags (Isaiah 64:6). So, who can live such a life?

God takes on the problem himself. "God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life" (John 3:16). The eternal Son, Jesus, sent by his Father in the power of the Spirit takes on flesh and lives the good and perfect life that we cannot. He takes us on our broken hearts at the cross, destroying them, without destroying us, so that we can be with him for all eternity. Jesus takes on our lack of goodness and the consequence of hell and breaks the power of death through his own good life and his own good death on the cross.

Dane Ortlund in his beautiful book, Gentle and Lowly, puts it like this: "The cumulative testimony of the four gospels is that when Jesus Christ sees the fallenness of the world all about him, his deeper impulse, his most natural instinct, is to move toward that sin and suffering, not away from it."

It is the very brokenness of our hearts which elicit Jesus’ compassion and move him towards us by moving him towards the cross – and out the other side.

Hope of heaven

I was moseying about the National Art Gallery in London the other week and stopped before a painting of the unbound Lazarus, fresh from the tomb, having just been raised back to life by Jesus. Before the painting stood a tour guide sharing with the member of his private tour in hushed yet excitable tones that when Jesus himself was physically raised to life after his crucifixion many of the dead in the city also appeared.

Jesus’s physical resurrection is assurance of the ‘good health’ we get to receive from him. Though our bodies will decay and die, those who trust in Jesus, will never die. We, too, will be raised. Not to a disembodied, merely spiritual state, but to a renewed earth, an earth not marred by the wails and wounds of war and death.

Above the gates of hell, the poet, Dante Alighieri, penned these words in his Divine Comedy: "Abandon hope all ye who enter here". Hell is final. Upon death, there is no time left in which to receive Jesus’ good life. Rather than have to abandon hope in hell, there is an opportunity to receive the hope of heaven through Jesus.

In such surveys as that of the one commissioned by SpiritShack, respondents sound much more like Christians who, along with C.S. Lewis, believe that there is a ‘straight line’ (which makes it possible for us to recognise crooked ones) and along with Martin Luther King believe that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice. They sound much more like Christians who believe in the good God who rescues than thoughtful atheists who say that they are cosmic accidents and none of our actions matter in the end anyway.

This Easter, let's take the words of the abolitionist John Newton to heart: "May we sit at the foot of the cross; and there learn what sin has done, what justice has done, what love has done."