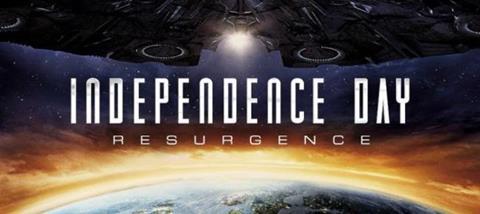

It is ironically coincidental that, just a few days before the release of Independence Day: Resurgence, Boris Johnson closed the EU Referendum debate on BBC TV with the words ‘I believe this Thursday can be our country’s Independence Day.’

It was probably coincidental, because I doubt that this film was on his mind at the time (though I hope he will watch it later). But it was certainly ironic, because the underlying concept of independence that was advocated by many in the discussions around the EU referendum contrasts with the underlying concept of ‘interdependence’ we see in the film Independence Day: Resurgence. As we all work through the implications of the outcome of the EU referendum I hope that many will see this piece of cinematic art and reflect upon what it means to be part of a global community.

When thinking about this film it is helpful to look back two decades to the original 1996 Independence Day, then a further two centuries to the work of the political theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and possibly even two or three millennia to other wisdom literature about the nature of humanity and community.

Galactic collaboration

The 1996 film Independence Day told the story of an enormous alien mothership arriving at the earth to destroy all life, and to strip the planet’s resources. That invasion was defeated by the collaboration of scientists and warriors. The scientists communicated with the aliens and encoded a computer virus that deactivated their force fields. This allowed the warriors to do their job and prevent the destruction of the earth.

Moving forward 20 years between the original and this sequel, and the corresponding time in the fictional events it describes, we find that co-operation and interdependence has extended across the planet. This has brought an unprecedented era of peace in which different nations work together for the common good. But now they face a second attack as another huge spaceship enters the earth’s orbit, with the renewed intention of destroying all life and stripping the planet’s resources. This time the same scientists, played by the same actors, collaborate with the new young generation of warriors drawn from across the world. And this intergenerational, international, co-operation is even set in the wider context of the need for galactic interplanetary collaboration.

Throughout history, art has often provided a critical counterpoint to existing cultural assumptions and this example of cinematic art continues in that tradition as it invites us to reflect upon the importance of co-operation and community. As we do so, perhaps it is helpful not just to look back two decades to the origin of the story, but also two centuries to the political concept of the ‘social contract’ as advanced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

A lesson from philosophy

Rousseau was born in Geneva (in 1712) and, although he moved a great deal around Europe, he generally signed his books ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva.’ That city was governed by a minority of the population who were accorded the rights of citizenship, excluding the large number of immigrants who lived there. Today he is best known for his book The Social Contract in which he developed the ideas he had previously published in his Discourse on Inequality. Rousseau was one of a number of political philosophers in his time who explored various forms of Social Contract theories which each considered how societies function through the members giving up some of their individual autonomy for the benefit of being part of a community.

The basic notion was that individuals freely consent, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their rights and freedoms to some form of governing body in return for the protection that this body provides to secure their remaining rights and freedoms. Rousseau, in particular, argued that societies should seek a consensus of the ‘general will’ whereby each citizen considers the good of all beyond their individual desires. Social contract theories were overshadowed in subsequent years by other political theories, but some of the concepts have been carried through into some aspects of the study of International Relations.

What does it mean to be independent?

In this increasingly globalised world we ask the question: what does it mean to be part of a global community? And this raises the deeper, fundamental question: what does it mean to be a part of humanity? That question has been asked for millennia, and explored in various wisdom literature.

The film Independence Day: Resurgence is a fictional story which implicitly advocates the concept of a global community working together for the common good. Could this be possible in the real world? Perhaps, as we all work through the implications of the outcome of the EU referendum, we might find some time to watch this piece of cinematic art and reflect on the questions it raises. We might look back two decades to the original film and consider how the theme of interdependence has been developed.

We might look back two centuries and consider what insights Social Contract theory provides for us as we seek to live together in an increasingly globalised community. And we might also look back two or three millennia, to other wisdom literature such as the Bible that might inspire us to consider the nature of humanity and whether all people may have been created to be part of a community designed to live together in a loving relationship with one another, and our creator who is the ultimate source of all authority.

This article was first published on the Ethos Film Blog (EthosFilmBlog.org)