The Second World War is often simplified down to a battle between Britain and Germany. In reality this was the most widespread and deadly war in all of human history and the majority of the 85 million casualties were not in Europe, but in the Soviet Union and China.

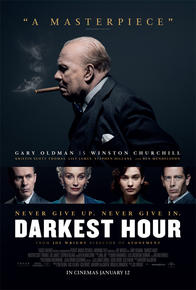

Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour does little to correct this common misconception, instead focusing solely on Churchill’s decision to fight Hitler’s Germany. But as other recent war films have demonstrated - the big screen is best suited to depicting smaller stories, even if the wider context is that of the entire world at war. Fury (2014) focused on a handful of US tanks in Germany while the critically acclaimed Dunkirk (2017) zeroed in on what Churchill called “the miracle of deliverance” - the evacuation of 300,000 British soldiers from a French beach.

The opening scenes of Darkest Hour are the perfect prequel to Dunkirk. The film begins with the resignation of Neville Chamberlain, providing context to Churchill’s unlikely rise to power. Before he can set out his strategy or deploy troops, the Prime Minister must fight for the hearts and minds of his colleagues in Parliament, the war cabinet, the king and ultimately the British public. Should Britain negotiate with Germany, or wage war? And can a man with such a mixed reputation really be trusted to command the country in its darkest hour?

The film reminds us that behind Churchill's bluster and arrogance was a man battling his own insecurities. We resonate with this leader’s need for affirmation and his inner turmoils and uncertainties about his own decisions.

Gary Oldman has already been tipped for an Oscar thanks to his stunning performance. The actor's portrayal of Churchill's moments of compassion and humanity are as engaging as the big speeches. While spending 200 hours in make-up and smoking 400 cigars during the course of filming might have helped Oldman get into character, it still takes a special talent to make Churchill come to life in a way which is both historically believable and somehow original. Lily James’ role as supporting actress is similarly impressive. Her character Elizabeth Layton is employed to work as Churchill’s typist, subjected to long hours and forced to hold back her emotions as the news from the frontline worsens and she fears for the safety of loved ones.

Good will overcome evil, even if our present circumstances suggest otherwise

Churchill’s oratory gift is depicted with great effect throughout. Not only in the classic “we will fight them on the beaches” speech but also in moments of humour. Shouting from inside the toilet in response to a telephone call he jokes: “tell the Lord Privvy Seal I’m sealed in the privvy and can only deal with one s*** at a time”. Of course, pedants will be ready to criticise the film for any perceived historical inaccuracies (including the above quote) but in the main, filmmakers have stayed true to real life events.

Battlefield scenes are largely missing from Darkest Hour. The drama is derived from government over guns. The seriousness of Britain's position in 1940 is made crystal clear. Our nation was in dire straits and Churchill's message was that the easy road of negotiations and compromise was not an option. Instead the country must fight the Nazis, and Churchill has little to offer the nation but literal blood, sweat and tears. 70 years on from these events, Churchill's great grandson Jonathan Sandys believes our political leaders should learn from Winston's candour:

There’s high tension and a clear message throughout Darkest Hour. In Churchill's words: "You cannot reason with a tiger when your head is in its mouth". Triumph through conflict and war is a very different theme to Mel Gibson’s equally strong WWII film Hacksaw Ridge where non-violence was lauded. Darkest Hour is a persuasive counter argument to strict pacifism.

Fans of Netflix’s The Crown will adore this movie - its historical drama at its finest. With 2018 promising more Brexit negotiations and pundits already predicting political turmoil, Darkest Hour is an opportunity for patriotic nostalgia. It’s not only a masterpiece of film making. It's a timely reminder that the light shines brightest in the darkness and ultimately, good will overcome evil, even if our present circumstances suggest otherwise.

Whether or not these 125 minutes make cinema-goers proud to be British, they should at the very least make us all grateful to God for a man who despite his faults was greatly used to save our nation from disaster. A world without Churchill doesn’t bear thinking about.

Darkest Hour is in UK cinemas from 12 January. For free community resources based on the film, visit baptist.org.uk/darkesthour

Click here to request a free copy of Premier Christianity magazine