On 24th June 2017, a new Messiah figure addressed adoring fans at the Glastonbury Festival. The adulation was immense as rapturous applause, cheers and impromptu singing resonated around the Pyramid Stage. T-shirts bore the man’s name and face, along with flags and home-made banners held aloft by the chanting crowd.

This figure spoke passionately about “out of the box” politics. He said a generation which was “fed up with being denigrated, fed up with being told they don’t matter, fed up with being told they don’t participate” was now seeking something very different from the failed politics of the past. “Another world is possible!” the prophetic politician declared.

Although he shares the Messiah’s initials, Jeremy Corbyn obviously isn’t our saviour. But followers of the real JC must admit that, until recently, neither the Christian Church nor our nation’s major political parties have been able to attract large numbers of young adults. The Church still has a missing generation. The Labour Party, it seems, does not.

Ever since Corbyn’s Labour leadership triumph in 2015, the Corbyn Effect has gathered momentum (pardon the pun). On a wave of popular youth appeal, Corbyn as suffering servant and capitalist reformer has captured the imagination of those seeking a new political future.

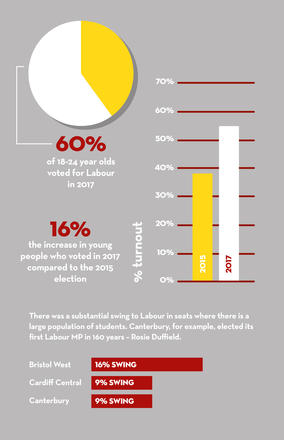

Many were surprised by the fact that a significantly larger proportion of young adults went to the polls in 2017, compared to the 2015 general election. Around 65 per cent of younger people voted for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party earlier this year and YouGov has observed that “age seems to be the new dividing line in British politics”, with older people tending to favour the Conservative Party and younger people generally voting Labour.

Without taking sides on the political issues, there’s still a significant question to be asked. How has Corbyn tapped into the hearts and minds of this millennial generation and what has Labour done to suddenly energise this group? The answers should inform Church analysts concerned about the lack of young people in many of our congregations, as much as it should inform political analysts.

Cultural shifts

In You Lost Me: Why Young Christians Are Leaving Church… And Rethinking Faith (Baker Books), David Kinnaman identifies three words which describe the social, technological and spiritual changes young adults have undergone. These three words are ‘access’, ‘alienation’ and ‘authority’. Kinnaman says that unless the Church recognises and embraces these cultural shifts then young adults are unlikely to engage with the Church because “they can’t understand what we are saying”.

1. Access

Young adults live in a world of screens. Through social and digital media they can access vast amounts of information extremely quickly. This sea of knowledge enables learning. It also enables connection with others, participation in shared causes and the ability to exert an influence. The power of social and digital media is incalculable.

Around 65 per cent of younger people voted for Jeremy Corbyn’s labour party

According to Who Targets Me – a project set up to monitor the use of social media adverts by the various political parties during the last election, the Labour Party’s advertising was more widespread and effective than the Tories’. What has become known as ‘alt-left’ political marketing comprises of a network of blogs and websites managed by social media savvy editors who know how video goes viral online.

The Tories produced video to watch but Labour produced content to share. It is this personal sharing of content which is at the heart of effective communication in the digital age. Labour won the battle of advertising, publicity and communication. They won in areas which the Church might traditionally call evangelism.

According to Kinnaman, this accessibility to social and digital media has brought in a new reality. Young adults expect to be connected to their communities at all times. They learn through participation and engagement just as much as listening to a talking head. They share knowledge and experience quickly and effectively. These are important lessons for the Church to learn when it comes to communicating with young adults.

2. Alienation

Young adults often feel a deep sense of alienation. This might be from family structures (which these days are increasingly unlikely to resemble the traditional nuclear family), community groups, church, political organisations and other institutions.

This alienation is most likely to happen when the group or institution in question appears to have no relevance or meaning to everyday life and appears distant, remote and disconnected. The less opportunity a young adult has to participate in, be of influence in and be a creative energy in these structures, the more likely it is that they will be disengaged.

Like the Lib Dems, SNP and Greens, Labour campaigned for the minimum voting age to be 16. In addition, Corbyn placed at the heart of Labour’s election manifesto the pledge that tuition fees for new students would be abolished from autumn 2017 and students part-way through a course would no longer have had to pay tuition fees from 2018. He also said that students already graduated from university would be protected from above inflation interest rises. Whatever one’s viewpoint on such policies is (and there’s been much debate about whether these were promises or merely aspirations on Corbyn’s part), one cannot deny they were a vote winner – they were relevant, meaningful and appealing. Promoting such policies for the Labour machine was Momentum, a grassroots campaigning network which arose from the 2015 general election. It encourages participatory democracy and activism targeting young adults (though not exclusively). It refers to the Labour Party as a ‘movement’ fighting for social justice and social equality. If nothing else it is seeking to combat the alienation that young adults have previously felt towards politics. As a grassroots network, it feels far less institutional.

Maybe we can learn from Corbyn here by asking how the Church can feel less institutional and hierarchical for young adults. Would it not be more attractive if the Church felt like a grassroots network, an activist movement with a cause? As Kinnaman puts it, “which model [does] the Church most resemble – the established monolith or grassroots network – and what might that mean for its relevance in the lives of a collaborative, can-do generation that feels alienated from hierarchical institutions?”

3. Authority

Jeremy Corbyn sharply divides opinion. Like Marmite, some hate him, while others love him. Yet many young adults see him in a very positive light. Approachable, trustworthy, normal, ordinary, in-touch, a listener, authentic and real. These are all words his supporters commonly associate with him. When the medium is the message, the personality and character of the party leader is so important.

Many young adults have an implicit distrust and suspicion of those in authority. Because of this, public figures liek Corbyn need to use their influence wisely. Before, during and after the 2017 election campaign, Corbyn has adopted an incarnational approach to politics (he is often refered to as a grassroots politician) and this has worked in his favour. For example, he met with individuals such as Grime artist JME. No doubt, such a meeting was strategic and intentional but it was far more casual and less choreographed than normal. Corbyn walked the streets in many cities (mostly marginal, of course!) and conducted openair rallies in ordinary places such as leisure centre car parks and town squares. His ‘preaching’ in the open air was a feature of the campaign. Subsequent to the election, his response to the Grenfell Tower fire when he met with locals who were affected by the disaster only reinforced his down-to-earth, people-centred image among many young adults.

Regurgitated, repetitious sound bites and platitudes don’t cut much ice anymore. Those who abuse their authority are not tolerated. Corbyn’s ordinariness, plain speaking anti-establishmentarianism has won him much support. Authority has to be earned as well as given.

Learning from Corbyn

Of course, the Church should never be naïve in paying homage to the cult of personality. Whoever performs or preaches at Glastonbury or Westminster is a mere mortal just like the rest of us. Yet learn we must. For if ever anyone has a mandate to be incarnational, reconciling the alienated, and energising the disenfranchised, it is us, the Church of Jesus Christ. And if ever anyone has been given a model of how to marry authority with integrity, it is us, through the person of Jesus Christ.

I’m not advocating for a particular party or style of politics, I’m simply pointing out the fact that Jeremy Corbyn has been the most successful leader in a long time to engage young people in his cause. Corbyn’s success in energising the millennial generation first identifies with their sense of alienation and second, offers visionary hope for a better future. This amounts to more than one or two particular relevant policies (although they help) but a call to participation and activism in a wider movement that feels less authoritarian and more dynamic.

Corbyn has adopted an incarnational approach to politics

Corbyn’s voice is now listened to by swathes of young adults because he has effectively contrasted his ordinary, in-touch approach with politicians of other parties who are perceived to be the very opposite. His voice is heard not only because he has earned respect and is endorsed by luminaries of youth culture, but also because his party knows how to effectively use the forms of media that young adults themselves use.

Perhaps the Church should be communicating something similar to a millennial generation that feels alienated from it? Using a variety of media, can the Church also present Christianity as a cause, a dynamic, grassroots Jesus movement; where participation is encouraged, where activism is valued and where hope is reborn? For surely Corbyn isn’t the first person to suggest that “another world is possible”?

Andrew Buttress is a church consultant and trainer. He is currently an ordinand at Cranmer Hall, Durham