What springs to mind when you hear the word ‘evangelist’? The gesticulating street preacher, or the person handing out tracts on the high street? The charismatic big stage speaker, or the friend who invites someone to every Alpha course?

There’s also another type of evangelist that is less talked about, but possibly more effective ? the everyday Christian willing to tackle the difficult questions and discuss the plausibility of the Christian faith, however challenging the environment.

Of course, some of those who take on this task are academics with multiple PhDs. William Lane Craig has doctorates in both philosophy and theology, and regularly debates with prominent atheists. Oxford professor of mathematics John Lennox is at the Oxford Centre of Christian Apologetics (OCCA), and has shared a stage with Richard Dawkins and many other militant atheists.

These well-educated brains are influencing a new generation of evangelists. Chris Sinkinson, a lecturer in Old Testament and apologetics at Moorlands College, tells of how his conversion was sparked by an evangelist who spoke at his college Christian Union. ‘He was such a breath of fresh air; he spoke of Christianity as being true and open to debate, and asked if there were any questions,’ he recalls.

‘I’d not even thought about Christianity in those terms ? that it was true rather than just a religion. I hadn’t known Christianity was quite so robust in presenting a true worldview.’

QUESTIONING DAWKINS

When David Robertson, pastor of St Peter’s Free Church in Dundee, read The God Delusion (Bantam Press), he was so annoyed with the poverty of its arguments that he went onto Dawkins’ website to tell him what he thought about it. The followers of the uber-atheist were not happy about his readiness to share his views. ‘I was so shocked, they were really vicious,’ he recalls. ‘I got banned from Dawkins’ website six times.’ But Robertson didn’t give up, and wrote a series of responses to the book and posted them on Dawkins’ website, and later published them in the book The Dawkins Letters: Challenging Atheist Myths (Christian Focus Publications).

Robertson’s heartfelt and persistent response proved worthwhile. It caught the eye of one atheist who was embarrassed by the behaviour of some of his fellow nonbelievers. He wrote to Robertson, saying, ‘I’m a lonely and sad atheist.’ Robertson wrote back, asking, ‘Why don’t you believe in God; and what would cause you to believe in God?’ It prompted him to read about Christianity and these words jumped out at him: ‘We loved him because he first loved us…’ He became a Christian and is now writing worship songs for a church in France.

These experiences show that even the most ardent atheist can be open to the gospel when we are prepared to put on our armour and engage with them. It is not only friendship, community, healings, preaching or Bible tracts that can reach people; reasoned debate, however hard we may find it, can make all the difference. ‘People say no one is ever converted through arguing. That is rubbish,’ says Robertson. ‘Of course people are only converted through the Holy Spirit, but he uses different means.’

IF THAT’S WHAT THE GOSPEL IS…

Sinkinson regularly encourages Christians to go and debate with their local atheist society. ‘That’s not everyone’s cup of tea,’ he admits. ‘But those formal debates get Christians face to face with atheists. They have to answer directly the difficult questions. Even if sometimes Christians go away feeling battered, it is faith-strengthening.

‘However militant and aggressive people can come across in debate, one to one they can be a whole lot more open-minded,’ he adds. ‘They can seem quite aggressively anti-Christian, but one to one they are far more receptive and open, and more self-conscious to their own weaknesses and doubts.’

We don't want to win arguments, we want to win people

He points out that debating with atheists has advantages over talking to other, less engaged, people. ‘The positive note to start on is that we share a concern with truth,’ he says. ‘Atheists can be asking a lot of the right questions. How could a god create the universe? How can we know Jesus is the Son of God?’ Robertson has spoken at atheist societies several times, and these relationships have even led to some atheist leaders visiting his church.

Michael Ramsden, European director of Ravi Zacharias International Ministries, spoke at a debate entitled, ‘Is Christianity inherently arrogant?’ at which the question and answer session afterwards went on for five hours, with the audience marvelling at the concept of grace and salvation through faith. ‘Even the Atheist Society said, “If that’s what’s the gospel is, you should be preaching it very loudly”,’ he recalls.

‘My experience has been, if you can take people’s questions seriously and deal with them meaningfully, by the time you come to the person of Christ and the crucifixion and resurrection and repentance, [it is] not automatically thrown out. Very often they are interested. They’ve never heard it before.’

A PLACE FOR APOLOGETICS

There is a lot of work to be done to equip churches to answer the difficult questions. ‘In general, churches are far too defensive, which is why I don’t like the word “apologetics”,’ says Robertson. ‘In a postmodern marketplace we have by far the greatest product. Putting the product out there, it is by far the most attractive. You see people going, “if [only] that were true”.’

Sinkinson points out that people need to be able to discuss their questions in a neutral environment. ‘We need to create space where people can engage with these ideas and debate them,’ he says.

Tom Price, an academic tutor at OCCA, suggests we should have an apologist in every church and provide youth workers with more training in apologetics. ‘Teenagers are very open,’ he says. ‘They really ask questions. If youth workers are not equipped to deal with those questions, it’s very tricky.

‘All Christian youth need to be going through basic courses in critical thinking and reasoning, so that when Richard Dawkins appears on TV, and says “My strongest argument is you can’t say who made God” ? they can see that’s an example of a logical fallacy.’

DUMBING DOWN

‘We can’t generally go to people and say, “you’ve got to believe in Jesus”,’ says Robertson. ‘They don’t know what “believe” is, or who Jesus is. They don’t see the need. People are more open to the gospel than they have been in 25 years, but the Church is less prepared to communicate it.

‘William Lane Craig is brilliant, but for 90% of people he needs to be translated into their language. We need to translate him for people who won’t go to a meeting in Westminster Hall, and haven’t got a philosophy degree. I still think the questions are fundamentally the same, though expressed differently.’

HOSTILE

Robertson regularly organises public debates in coffee shops and other neutral spaces, where members of the public are encouraged to come and ask questions. But the question of God can provoke powerful feelings. ‘People are very, very hostile,’ he says. He remembers a man in Brighton who was very aggressive. But when Robertson asked him why he was criticising the Bible when he’d never read it, it got him thinking. He started reading Genesis, and wrote to Robertson, saying, ‘It is scaring me because it’s beginning to make sense.’

‘The best apologetic book by miles is the Bible,’ says Robertson. ‘A lot of Christians are using arguments; in fact, what we find is that as we communicate the Bible, it answers people’s needs.’

People are more open to the gospel but the Church is less prepared to communicate it.

But that doesn’t mean there won’t be attacks. Robertson receives hate mail. ‘People are not apathetic; the Bible says people hate God,’ he says. ‘I’ve had death threats, legal threats… to say nothing of the spiritual oppression that sometimes occurs. When I was first doing The Dawkins Letters I was getting abuse and swearing ? it was just constant. I was lying in bed and got an overwhelming sense of evil and dread.

DEBATING WITH LOVE

In this atmosphere, it’s hard not to get defensive. Alister McGrath in his recent book, Mere Apologetics (Baker Books) warns that those interested in rationally defending the Christian faith mustn’t forget that their calling is to love. ‘The word I would have is winsome,’ he tells Christianity. ‘You’ve got to say this does make a lot of sense, but not forcing it on them…trying to be gracious rather than battering them into submission. We don’t want to win arguments, we want to win people.’

McGrath warns that if we’re not prepared to answer questions, and state the reason for the faith we have, some may reject faith as a result. ‘As an apologist, I occasionally meet some people who are aggressively anti-Christian,’ he says. ‘What made them like this was somebody taking a very anti-intellectual viewpoint; that faith is all about not using your head, refusing to think and just trusting. People who say this kind of thing do create a lot of damage.

Equipping ourselves to enter into debate, however hostile, can fortify our own faith. We should remind ourselves that the questions posed by popular atheists can be answered. Meanwhile, we may find that while the courses and the evangelistic talks remain important, this kind of evangelism is increasingly necessary in a secular Britain.

Further reading

Amy Orr-Ewing // But is it Real? Answering 10 Common Objections to the Christian Faith // IVP

William Lane Craig // On Guard: Defending Your Faith with Reason and Precision // David C Cook Publishing

Lee Strobel // The Case for Christ: A Journalist’s Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus // Zondervan

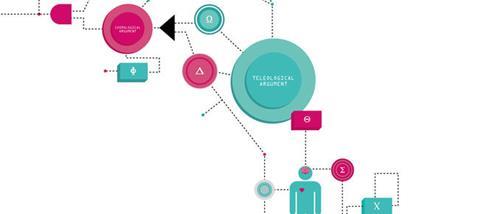

12 rational reasons to be a Christian

1. Maths and physics: The universe contains numerous physical and mathematical constants and qualities that are precisely right for the existence of a material universe and living beings ? so precise that it’s difficult to argue how they were not designed this way.

2. Big Bang: Most scientists think the universe began at a ‘big bang’ millions of years ago ? if so, what created something out of nothing? What, or who, caused the Big Bang? When this theory first appeared, atheists were concerned that it showed evidence for a creator.

3. Meaning: A materialist view that we are just the accumulated product of random collections of molecules is very bleak. The Christian story gives more significance and meaning to our lives.

4. The Bible: We can be confident in the accuracy of scripture ? there are more copies of the New Testament than any other ancient manuscript, and scholars are certain of the authenticity of nearly all the content.

5. The resurrection: There is good evidence that the resurrection took place. Why would the disciples have been so motivated to evangelise and suffer for their faith, if they knew it was a lie?

6. Morality: Why do we know there is wrong in the world? The sense of an objective right and wrong is a strong argument for the existance of God.

7. Prophecy: The fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy. Jesus’ story strongly resonates with words written hundreds of years before.

8. Philosophy: Thanks to philosophers such as Alvin Plantinga and Richard Swinburne, theism is increasingly accepted in academic philosophy. Between a quarter and a third of philosophers are theists.

9. Your story: The changed lives of people who have found Jesus show the reality of God among us and the truth of redemption. From drug addictions to depression, many seemingly insoluble problems have been overcome by faith in Jesus.

10. Inspirational faith: Christian faith has inspired some of the most important social changes in history. From ending the slave trade to protecting prostitutes in law, Christian love has inspired many thousands of people to act for the betterment of humankind.

11. Believing scientists: Around 40% of scientists believe in God. If belief is irrational or unscientific, why do so many believe.

12. Afterlife: The existence of near-death experiences, where people have an intense spiritual experience even though their physical body is dead, is evidence for some form of afterlife.