Freedom of expression and freedom of speech are fundamental human rights long enjoyed in Western society. But contrary to popular belief, totally free speech is an impossibility even in the most progressive liberal democracies.

Holocaust denial is against the law in Germany. Many countries have laws against defamation and false advertising. And speech which incites violence or religious hatred is illegal in the UK.

With this in mind, the question becomes not ‘Do you believe in freedom of speech?’ but ‘Where do you draw the line?’

Events in recent months (see Culture, p22) suggest the line is being drawn in ever-more restrictive ways for people with unpopular views. A handful of street preachers have been arrested in UK towns and cities for announcing in public that the Bible says homosexual behaviour is sinful. Employees have been sanctioned for sharing their faith in the workplace (one NHS worker was suspended after giving a Christian book to a Muslim colleague) and Core Issues Trust were banned from running an advert on London buses which was to read: ‘Not gay! Ex-Gay, Post-Gay and Proud. Get over it!’

>

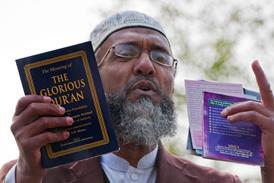

Freedom to preach

Campaigners have argued that last month’s case of Pastor James McConnell – who was taken to court for calling Islam ‘satanic’ – is further evidence that free speech is under threat in the UK.

The 78-year-old pastor had said during a sermon in his church in Belfast, ‘Islam is heathen, Islam is satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in hell.’ After the message was broadcast online, two charges were brought – improper use of a public electronic communications network and causing a grossly offensive message to be sent by means of a public electronic communications network.

Pastor McConnell could have accepted a warning from police, but he refused. His personal stand landed him in court.

The pastor argued in court that he’d never intended to provoke, hurt or offend anyone. He remained unrepentant for his words and said he was ready to go to prison for his beliefs. In the end, his right to freedom of speech and religion was upheld as district judge Liam McNally ruled the pastor was ‘not guilty’ of both charges.

Summing up, the judge said, ‘The courts need to be very careful not to criminalise speech which, however contemptible, is no more than offensive. It is not the task of the criminal law to censor offensive utterances.’ Prosecutors had argued that McConnell’s statements were ‘grossly offensive’ and therefore illegal. However, the judge ruled the pastor’s words were only ‘offensive’ and therefore legal. In the meantime we are left with little clarity as to where the line between ‘offensive’ and ‘grossly offensive’ actually lies.

‘A victory for the gospel’

Speaking to Premier immediately after the verdict, McConnell said he was ‘very happy’ with the outcome, calling it a ‘victory for the gospel’.

However, he predicted similar cases would follow: ‘I’m deeply disturbed about the way Christianity is being treated in Britain and particularly in Northern Ireland. I think they were using my case as a specimen case and had they won every evangelical preacher worth his salt would be tried in court.’

Given that, in the words of the Evangelical Alliance (EA) Northern Ireland, the McConnell verdict was a ‘victory for common sense’, questions have been raised over why the case was allowed to reach court in the first place.

The EA added that Christians should nevertheless be wary of causing unnecessary offence. ‘It is vital that the State does not stray into the censorship of church sermons or unwittingly create a right not to be offended. Meanwhile, the Church must steward its freedom of speech responsibly, so as to present Jesus in a gracious and appealing way to everyone.’

Christians, Muslims and Secularists unite

It was reported that a crowd of up to 50 Christian supporters in the public gallery erupted into applause when the ‘not guilty’ judgement was given in the McConnell case. But it wasn’t just Christians who were relieved at the outcome. Muslim academic Sheikh Dr Muhammad Al-Hussaini supported McConnell throughout the case.

Writing on the Premier Christianity blog he argued that while McConnell’s style of preaching may be controversial in the West, it was familiar to millions of ‘non-white, non-wealthy, non-Western Christians’, as well as many Muslims who are also used to a ‘bluntly scriptural style’.

The National Secular Society (NSS) also welcomed the verdict as a ‘victory for free speech’, and a ‘welcome reassertion of the fundamental right to freedom of expression’.

They added, ‘At a time when freedom of speech is being curtailed and put at risk in any number of ways, this is a much needed statement from the judge that free speech will be defended and that Islam is not off-limits.’

It is not the task of the criminal law to censor offensive utterances

A Muslim scholar and secularist campaign group may seem like strange bedfellows in Pastor McConnell’s battle for victory, but is indicative of the fact that many people believe a war on freedom of speech is taking place today. In another unlikely alliance, the NSS has also teamed up with The Christian Institute to oppose the UK government’s proposed anti- extremism measures as they believe these could lead to further suppression of free speech (see p26).

In the meantime, McConnell has vowed to continue to preach the gospel ‘without fear or favour’ and ignore the judge’s plea that he be more ‘careful’ with his words.

But given the ordeal McConnell has endured in being dragged before the courts, the possibility exists that other preachers will think much more carefully about what they say, how they say it, and whether they want their sermons made public on the web. McConnell may be a test case for what is still deemed acceptable today, but whether another case will shift the balance in future remains to be seen.