He’s the classic bad guy. A member of an inner circle of comrades, and utterly trusted, he becomes a traitor. An innocent man’s blood is shed because of his betrayal. He sides with the enemy, and sets his friend up with furtive whispers. He is smarmy, affirming love for his friend even as he sets him up. And there’s no happy ending for this particular villain. Shame overwhelms him, but he feels that it’s too late, he’s gone too far. He ends his days tragically.

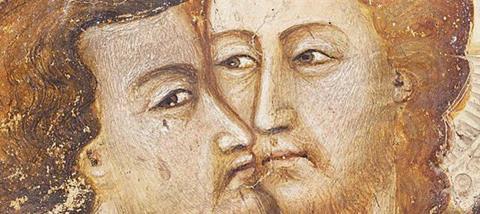

The villain in question is Judas Iscariot. Preachers don’t like to talk about him too much, because there’s not much hope in his story. We wrinkle our noses in disdain when we hear his name. Surely the most well-known traitor in history, Judas Iscariot is never mentioned in the gospels without the added tagline, “the one who betrayed Jesus” (Matthew 10:4; Mark 3:19; Luke 6:16).

Despite spending three years as a member of Jesus’ team, Judas is remembered simply as a traitor; it’s the headline over his life. How could he, trusted treasurer to the Jesus team, do what he did? We are tempted to simple label him as one of history’s most notorious losers. But we can learn from epic, awful failure - and Judas in a vivid example of that. There are insights to be gained from stories of weakness as well as strength. And here’s an awkward, painful thought - perhaps you and I are a little more like Judas than we’d like to admit.

Of course, no traitors kiss will come from our lips. But when we step back back from what Judas did, and consider why he did what he did, we might learn some vital lessons from his awful journey.

We know that he had in his hand in the till, or more specifically, the bag of funds that he had been given responsibility for. Perhaps things began to go wrong when he viewed what he managed as being his - and he helped himself.

Rather upset by Mary anointing Jesus’ feet, he huffed and puffed and blethered on about how money from the sale of that expensive perfume could have been used to care for the poor, but John makes it clear: "He did not say this because he cared about the poor but because he was a thief; as keeper of the money bag, he used to help himself to what was put into it." (John 12:6)

We don’t have to steal from the church to fall into the same sin; there are more subtle tripwires that can cause us to stumble. When we start to view the church that we attend as ours, designed primarily to serve us, our needs, our preferences, we begin a journey that involves taking for ourselves what is intended for all. In our consumer age, when we are used to getting things our way, it’s an easy snare.

But perhaps another possibility is that we try to manage God. Did Judas betray Jesus, not only because he was disappointed with him, but because he wanted to steer him in a direction of confrontation with the authorities?

Remember that the Jews wanted a military Messiah, one who would deliver them from the oppression of the Romans. Living under the heel of another nation, where the occupiers were exacting heavy tax burdens and harsh controls, the people of Israel longed for a human rescuer. When Salome, the mother of James and John, heard that Jesus was heading for Jerusalem, she went to Jesus and asked for thrones for her boys - she thought this was the moment for the long-awaited takeover. And the idea lingered even after the resurrection, because the early believers were still asking, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). While not certain, it is possible that Judas so wanted Jesus to take that political route, and betrayed him because he was headed to a cross instead.

Matthew tells us exactly when Judas decided to finally go through with his betrayal scheme, it was after the moment when Jesus was anointed for burial. At this stage, Judas knew for sure that triumph over the Romans in Jerusalem was not going to happen, Jesus was determined to head toward death. And instead of rebuking the occupiers, Jesus was concentrating on rebuking some of his own people, the Jews - such as the Pharisees and the money changers in the temple courts. And so, some think that, with the smell of burial spices in his nostrils, Judas set up the betrayal in the hope that this would force a showdown, and edge Jesus into the role of a military Messiah. When we consider that Peter drew his sword and chopped of a hapless chap’s ear, as the beginning to a fight, we can see that Judas might not have been the only disciple with a confrontational plan.

Jesus had to contend with the challenge of people who repeatedly tried to manage him. The disciples wanted to send parents and children away; Peter didn’t want Jesus to go to the cross; Martha and Mary were upset when he didn’t immediately go to help Lazarus. And the Pharisees and their pals were always trying to control him.

And Judas shows us that we can not only try to manage God, but then get upset when we can’t force him to do what we want. Resentment drives trust out of our hearts. Let’s be careful when our repeated prayers seem to go unanswered, or when God seems set on pursuing a direction that we don’t like. He is God, and although the invitation to prayer means he is open to suggestions, ultimately he decides. Let’s allow the challenge to come to us: “Where am I trying to manage God?” Let God be God. It’s a call that we all need to heed.

George Bernard Shaw said, “God made man in his own image. Unfortunately man has returned the favour’. Let’s not fall into that trap.

This article is adapted from Jeff's latest book Notorious: An Integrated Study of the Rogues Scoundrels and Scallywags of Scripture (David C Cook)