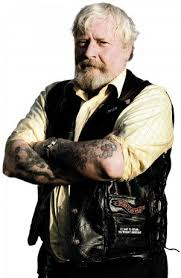

Catherine Butcher meets the ex-con who's helping prisoners escape

HM Prisons won’t give chaplaincy worker Brian Greenaway the key to prison cell doors – he’s an ex-con. But a higher authority is giving him access to men’s hearts – and they’re being set free.

Brian Greenaway became famous when his book Hell’s Angel became a top best-seller in the 1980s. It has since been translated into nine languages and was the first contemporary Christian book to be used by the church in Greece.

Being an ex-Hell’s Angel is the tag that set Brian off on the testimony trail 30 years ago. These days he’s more likely to describe himself just as an ‘ex-con’ and the evident pain of recounting his story suggests he’s looking forward to a time when he can throw off even that label.

Brian became a Christian in 1973 while serving a four-year prison sentence in Dartmoor – his fourth prison stretch. He was first caught breaking and entering as a 12-year-old and was given three years probation. The probation officer talked Brian’s mother into letting him move to a children’s home; his dad had left home when he was four and he had grown to hate his step-dad. While living in care, Boys Brigade and the local Baptist church were his first encounters with faith. But nothing overcame his sense of loneliness.

By the age of 16 he was living on his own. He was already experimenting with drugs, and his petty thieving meant he was on the wanted list. Once he was caught, he was back before Petersfield Magistrates, this time facing three months in Gosport detention centre.

Not long after his release, Brian saw his first Hell’s Angels during sea-front riots in Brighton: “They wore sleeveless denim or leather jackets and heavily studded belts. On the back of every jacket was embroidered a skull and around it the words Hell’s Angels… I was impressed by the way they were fighting. And later, when I saw their bikes, shining and strange, like no other bikes I’d ever seen, it really blew my mind.”

He did have a brief stint in conventional employment with the Electricity Board, but he had a violent temper. One fight too many left him jobless with only bikers, junkies and drug-pushers as companions. Copying the American Hell’s Angel lifestyle with a bike as his idol and altar gave him the close-knit family he’d never had. “Because I talked tough and was always in the front when there was any action, they listened to me. Under my influence these guys became rebellious and anti-authority, ready without reason to run down a scooter-guy or kick a copper’s head in. I used them to release my pent up anger and to get back at the world I hated,” says Brian.

Drugs made his temper worse. “They could make me freak out at the smallest thing which annoyed me.” Fights flared and finally led Brian back to prison. His first stretch in Winchester was followed by another 18-month sentence when he served time in Lewes, Wandsworth and then Chelmsford maximum security prison where he was introduced to LSD. “I tripped nearly every day during the 12 months between my release and my final four-year sentence in the Moor.” On one drug-induced trip a white figure appeared in front of him “not blinding white but clean and pure and good”. Brian was convinced he had seen God and had talked to Him despite his drugged state.

In the autumn of 1972 Brian was back on the streets, still president of his Hell’s Angel chapter when he was arrested for the last time. He’d stabbed two skinheads in a gang fight in Bognor, leaving them fighting for their lives. After three months on remand in Winchester prison, Brian was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. Because of his drug abuse, detention under the Mental Health Act was considered but two psychiatrists had agreed: “They both reckoned I was hellbent on self-destruction and too violent to be detained.”

The journey to Dartmoor began as an ego-trip: “I knew I was going to the real con’s prison”. But arrogance turned to fear. Could Dartmoor turn a man insane? “I sensed it was an evil place. ‘This is it,’ I thought. I was trapped. I started to shake.”

Alone in his cell he had time to think of the people he’d terrorised and maimed: “Over and over again I remembered that I had been rejected by my family. It was a scar that never healed.” He had no visitors until the Welfare Officer asked if Brian wanted a visit to be arranged.

“OK, but I want to talk about God” was Brian’s response. He had started attending Sunday services at the prison’s Methodist chapel “to meet my mates and have someone to talk to”. The chaplain had given him a Methodist Recorder and an advertisement for The Living Bible had caught his attention. So when his visitor arrived and asked if there was anything Brian needed, he asked for a copy.

On his 27th birthday his Bible arrived together with a copy of Run Baby Run about New York Gang leader Nicky Cruz whose life had hit rock bottom like Brian’s. Nicky Cruz had asked God to change him. Brian was in tears as he read how God had changed this fellow criminal. He began to read the Bible and realised Jesus was speaking to him, offering to change his life. Brian responded out loud, inviting Jesus to make that change and physically felt the poison drain from him and the love of God pour in. He woke the next morning knowing he was a new person.

More than 30 years later, Brian’s story has helped many men to make that same change. On his release Brian lived at a Christian hostel for drug addicts for five months. He was no longer a junkie, but there he was able to see Christian love in action. Soon he began to tell his story to help others on their journey to Christ.

Within a short time he was married to Claire, living in the New Forest in a caravan and attending Moorlands Bible College. His training included a twoweek practical stint in London, working with London City Mission. That became a four-month trial period with the mission, followed by a job running a mission hall on the Isle of Dogs.

Brian, Claire and their first child Emily had exchanged the New Forest countryside for East End dockland. It was a tough area spiritually “but the people were real diamonds,” Brian says. He had wanted a challenge and found that he loved preaching as well as teaching five year-olds in Sunday school. Prison work wasn’t something he wanted to do, but onceHell’s Angel a best selling book which told Brian’s story was published in 1982 requests kept coming from prisons asking him to tell his story. He has been doing just that ever since.

Reliving the hell of his former life is not easy, but prisoners can relate to him. Brian’s attitude to people in authority has had to change as God has worked in him. Now he feels “the public treat the police terribly; prison staff are badly treated too – it’s a tough job for officers.” Brian always treats officers with respect, calling them “Sir”. In one prison, an officer became a Christian when he heard Brian explain “Christianity is not for nice people – it’s for people who know they’ve done wrong”. Brian admits that he struggles with “nice Christianity”; the faith he talks about is challenging and tough, especially for men who respond to Christ in prison.

As the requests from prisons increased, Brian formed a trust to support his work and began working full time with prisoners and ex-convicts. He is also a founder trustee of the Stepping Stones Trust which now has three homes for ex-offenders.

Brian’s four years at Her Majesty’s Pleasure have become a life sentence as he spends Sunday after Sunday leading services in prisons around the country and visiting men in their cells. But it’s a life sentence Brian wouldn’t swap for anything – except perhaps a fishing trip in Cornwall. But even on his days off, he’s always looking for an opportunity to make a prison visit.

He sees inmates with all sorts of problems. Some are volatile and dangerous, but Brian finds he is often able to calm them down. Conversations that particularly thrill Brian run along the lines of: “Can I talk to you about God? I’m in for murder. Can God forgive me?” It’s a privilege to lead a man to Christ. Word gets round when a prisoner becomes a Christian. At one point Brian was seeing a man a day who wanted to become a Christian.

Brian is now part of the chaplaincy team at Wandsworth Prison and has his own set of keys to all areas, except the cells. Ex-offenders are not given unsupervised cell access. He sees men as they arrive to start their sentence. “If you’re serious about changing, I’ll support you all the way” is his opening gambit. That gives some men hope and every now and then, he meets someone who has read his book or who says, “I’ve been trying to find God for a long time.”

Sometimes it’s easy to see that God is at work. He met one new inmate – a 40- year-old psychologist with an Australian accent – and asked: “Is there any way I can help you?” The man’s response was, “I prayed for the first time last night.” God was already answering that first prayer. When that man turned to Christ his face shone with happiness; he gave his testimony two weeks later to a room full of mainly black inmates – real hard men; they gave him a standing ovation, his story was so powerful.

But it’s not always plain sailing. One ‘success story’ turned to tragedy recently. A close friend and fellow ex-con who had become a Christian, was helped to go straight through the Stepping Stones Trust. After working with a local church and training to be an Anglican minister this man was married and working in his own church when he became depressed and committe suicide. Brian has been particularly badly shaken by that loss.

Also, his own family life has not been easy. His marriage to Claire ended in divorce. The marriage breakdown lost him half his supporters. When he later married Jennie, who he had met through prison visiting, many more friends dropped him.

“A lot of my work is with people who have failed”, Brian says. And he feels qualified to help on that score. He makes no pretence of personal success. “I try to live with my humanity. That’s the reality of following Jesus.”

He now works with “The Twenty-five Trust” named after Matthew 25:35-36 “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

The trust employs Brian to evangelise and promote Christian teaching among prisoners, to counsel and assist exoffenders and their families, and to work in schools, speaking on drug abuse, crime and punishment. He meets regularly with a supporters group – much needed as he finds the work especially draining.

Most of us make mistakes. Many, like Brian, make those mistakes in their teens and twenties but can leave them behind. Brian’s life and work remind him every day of the ugliness of his past with its violence and loneliness. That’s painful. And working with broken people means not every story has a happy ending. But God has given Brian an overdose of grace: genuine love for guys like him who come face to face with their own terrifying emptiness when the prison door bangs shut.

One prisoner wrote: “Dear Brian… after spending 40 years locked up I cannot reconcile myself to accept Jesus. Please help me to come to terms with my past… my sins are so horrible, if only I could receive Jesus I know my life would be worthwhile.”

That man is now a Christian, reconciled to God because of Jesus. As Brian says, “Along with many others in our prisons, he is proving that the Gospel of Jesus is far more than just a story. Jesus is helping people in our prisons to find a real way of escape.”

No comments yet