When comedian Ross Noble appeared on the BBC2 show Room 101, where celebrities list items they would most like to eradicate from the world, his first choice (ahead of “people with clipboards”, “Craig David” and “people who look like cats”) was Christian rock bands.

The thought of them going on tour and “tidying hotel rooms” was just a passing objection. His major issue was that Christian music is bland and boring, and he’s not alone in holding that view. Today, many God-loving bands avoid the label ‘Christian rock’ at all costs; the term carries a negative connotation in the minds of many, but this wasn’t always the case.

The birth of Christian music

A denim-clad hippie with shoulder-length blond hair was the pioneer who gave young Christians their own music 50 years ago. Commentators generally agree that Larry Norman’s 1969 album Upon This Rock (Solid Rock) marked the beginning of Contemporary Christian Music. He had already seen chart success with his band People!, but was peeved when his label blocked his proposed album title ‘We Need a Whole Lot More of Jesus (and a Lot Less Rock & Roll)’, from the 1950s country song. So he quit. And with his signature ‘One way’ upwards-pointed finger gesture, denoting Jesus as the only way to salvation, he became the poster boy for new Christian music.

Norman’s landmark album Only Visiting This Planet (Solid Rock) sealed his place in history. And crucially, the album’s approach still works as a template of what Christian music, at its best, should be. The songs clearly spoke to the world around, critiquing contemporary society, making a stand for Christian values and pointing the way to Jesus.

That’s not to say Only Visiting This Planet was appreciated by everyone. Norman’s reference to gonorrhoea didn’t go down too well in the Christian market, and the singer was often described as being too religious for rock and roll stores, and too rock and roll for the Church. Cliff Richard remembered a similar tension in his music when he spoke to me some years ago: “There was a feeling that rock and roll and church didn’t go together...I remember reading of Christian fundamentalist preachers in America burning rock and roll records– and thinking: ‘Oh, my goodness, that’s me!’”

Light up the fire

Singer-songwriter Bryn Haworth also felt the church-rock tension. He was on the groundbreaking Island record label’s original roster, and gained a reputation as England’s leading slide guitarist. He came to faith after strangely experiencing someone onstage with him one night, whom no one else saw, and later finding himself in a revival tent, thinking it was a circus. He recalls: “After a year of churchgoing we thought: ‘We can’t do this; it’s too alien a culture’, and were about to give up. Garth Hewitt, a fellow Christian musician, who was keeping a pastoral eye on us, recognised we were struggling and invited us along to the Albert Hall to see Larry Norman. We went along reluctantly, but loved it, and were so encouraged. We thought: ‘Well, if he can follow Jesus and be himself, then so can we.’”

A rare example of a track hitting the charts and being printed in youth groups’ songbooks at more or less the same time was folk trio Parchment’s 1972 ‘Light up the fire’ which was the theme song to the Nationwide Festival of Light (a Christian movement aimed at reducing ‘moral pollution’). Premier Christianity’s predecessor Buzz magazine noted that Radio One DJ Tony Blackburn said he wouldn’t play it, even if it got to number one, showing that both sides of the culture gap had their issues.

Green and Dylan

The groundswell of Christian teenagers looking for integrity in their music in the 1970s led to a small but growing list of artists whose quality matched their enthusiasm. In the States, rock bands Petra and Resurrection Band were pioneers, while English prog band After the Fire were so good that they headlined both the first and last nights of the Greenbelt Festival in 1975.

Having started to play the ukulele at age three, and becoming the youngest person ever to sign with the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) at eleven, a young Keith Green was named in Time magazine as Decca Records’ “prepubescent dreamboat”. When he and his wife, Melody, came to faith, his work became so spiritually charged that some called him a prophet. After agreeing a release from his record label, he refused to charge for either albums or shows, asking people to pay what they could afford. He ended up giving away thousands of copies of his next album, the less fiery and more pastoral So You Wanna Go Back to Egypt. Guesting on harmonica on that album was the most dramatic of the many well-known conversions taking place during that time...

For counter-cultural icon Bob Dylan to espouse what many saw as the institution of Christianity was the biggest shock to his fans since he turned electric at Newport in 1965, and probably gave them an even greater sense of betrayal. Several members of Dylan’s mid-decade backing band for The Rolling Thunder Revue tour had come to faith and were associated with the new Vineyard Fellowship. In a hotel room in late 1978, Dylan had an experience of Christ and later claimed: “There was a presence in the room that couldn’t have been anybody but Jesus...Jesus put his hand on me. It was a physical thing. I felt it all over me.” Dylan released three Christian albums after that (Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot of Love). Within a year of the last being released, three of his colleagues were dead. One was Keith Green, who died in a plane accident.

1980s: The rise

With a host of professional musicians, such as Santana singer Leon Patillo and Earth Wind & Fire’s Philip Bailey coming to faith, CCM became far broader and deeper in the 1980s. Celebrated Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn and Alice Cooper also made commitments to Christ.

At this stage, CCM was not a monochrome genre, but a term to bind together music with Jesus at its heart. It was losing the initial safeness it had when rock cautiously infiltrated Church culture. As a result, it displayed a range of sonic colour, as creative artists did what they do best: Glen Kaiser brought blues; Phil Keaggy had begun his journey into world-class instrumental guitar; The Choir drew indie into the Nashville scene and Steve Taylor brought punk, infusing it with an unusually intelligent and acerbic wit. DC Talk encapsulated this by drawing together three genres within one band and went on to become one of the biggest-selling Christian acts of all time.

In 1985, U2’s Bono and his wife, Ali, spent a month quietly working at an orphanage in Ethiopia. U2 had played Live Aid only weeks before in 20 minutes that turned their appeal global. Now, Bono was finding out first-hand about the famine crisis, and later learned that the £250m raised by Live Aid was as much as Africa spends every couple of weeks to repay loans to the richest nations. The fight against this structural injustice would colour his life and music from then on. The band that was formed in violent Dublin and exposed to a smorgasbord of faith expressions, from Catholic to ultra-evangelical, now had a personal understanding of global politics, and Bono would go on to talk to world leaders about issues of justice. U2’s output now had an integrity of faith, creativity and activism that set a new standard for how to do music, Christian or otherwise.

1990s: The highpoint

The early 90s saw an explosion of Celtic-flavoured music, yet by the time that Riverdance was first performed during the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest interval, Iona – a group of Christian session musicians, who came together to produce their own rock-Celtic hybrid – were already on their third release. Their fourth record Journey into the Morn made

Q magazine’s top five folk albums of the year. Later, when Rob Beattie reviewed Delirious?’s Mezzamorphis for the same publication, he noted how it was: “Something of a rarity this, a Christian band who are neither Celtic nor crap” before going on to observe with prescience how they were nicely poised in their career, selling well with vision intact and everything looking rosy.

Christian music had been given a template to communicate to the secular world with lyrics that critiqued the culture from a distinctly Christian perspective, putting Christ centrally in that worldview. Some of the biggest musical names on the planet were now avowedly Christian. Secular record companies were setting up Christian divisions to capture the hunger for God-centred music and putting in resources, so that it was sounding more professional than ever before. Surely, with all this momentum, Christian music would make a dramatic impact on our culture?

The fall

Paradoxically, it was the success of Christian music that led to its failure. The industrialisation that managed people’s demands for Christian music ended up being the cause of its own demise.

In the 90s, sales of Christian music albums exceeded those of classical, jazz and new age music. Supply could not keep up with demand. Record companies had to keep signing bands, just to keep the machinery of business going, feeding the playlists of Christian radio stations in the USA with new material. In the rush to sign new acts, labels became less discerning about who to back. Bands with little character or talent found themselves being snapped up by the industry.

Not only did this increased supply inevitably mean lower quality, but the need for predictable sounds to fill the specific styles of those shows meant that Christian music gradually became part of a commercial monster that was unable to cope with creativity. And with secular labels dictating content, the desire to impact the surrounding culture for Christ faded away. Instead of being on the cutting edge and pushing creative boundaries in the way Larry Norman did, CCM turned in on itself and became safe.

Emmy Award-winning television producer Bob Briner saw the danger signs, writing the book Roaring Lambs (Zondervan) in 1993, which urged Christians to infiltrate and impact their workplace and world with their faith. The eponymous CD it inspired featured Christians who were doing just that in the mainstream music industry, avoiding the temptation to simply ‘play for the choir’. It included Steve Taylor, Over the Rhine, Sixpence None the Richer, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Jars of Clay, Delirious? And Charlie Peacock.

Sometimes good things can be overdone. By the end of the 90s,the modern worship movement was placing a great emphasis on intimacy in worship. Songwriters were making worship appropriately personal. Its popularity in the Church – and the ease with which such lyrics can be banged out – was another driver for record companies to chase the safe money and roll out the formula. Writing for the Cross Rhythms website in 2006, Larry Norman was searing in his criticism, claiming the labels’ approach had been one of “calculation, imitation and saturation”

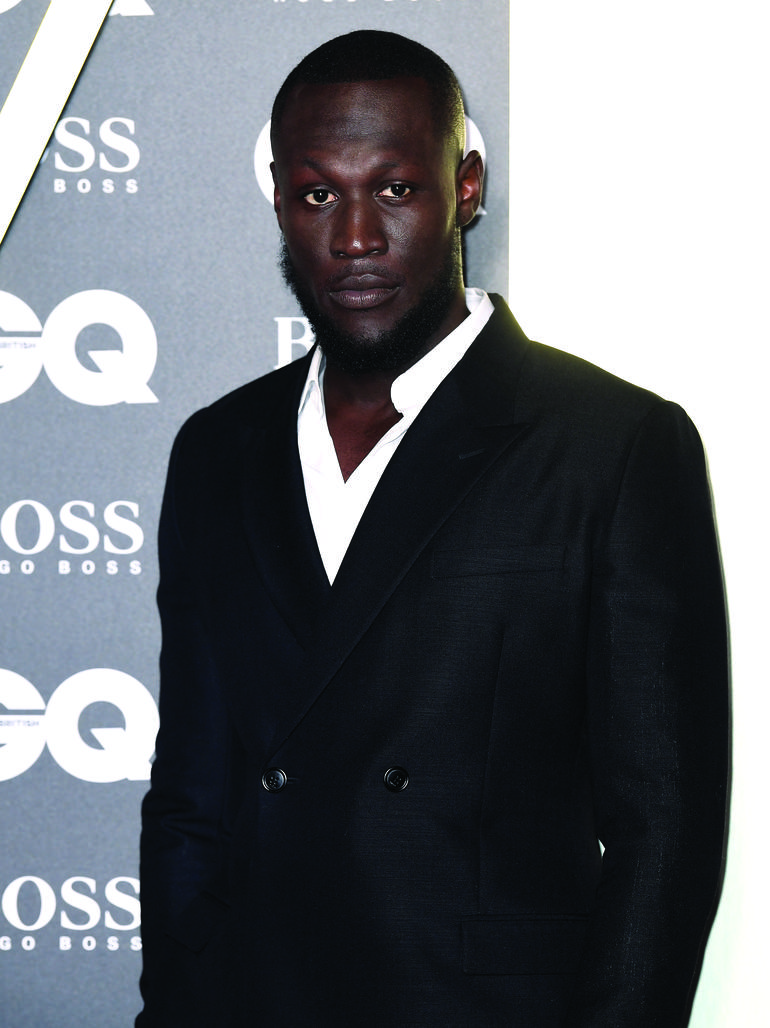

Kanye, Bieber and Stormzy

The glory days of CCM are over, but God is still at work. The alt-folk all-female trio Wildwood Kin who are signed to Sony and recently charted, see their music as a force for good and are determined to keep their faith central. They’ve played everywhere from the Big Church Day Out to Glastonbury, proving it’s still possible to be successful in both the Christian and mainstream arenas.

Perhaps most notably of all, Justin Bieber – a man with greater musical talent than he is often given credit for – was raised an evangelical Christian and struggled for a while due to the ever-dangerous mix of being young, famous and rich. But since deciding to return to the faith of his upbringing, he has celebrated it across many platforms: “I feel invincible like, nothing is bigger than God,” he told Complex. “If God’s for me, who can be against me? That’s helped me in a lot of situations where I feel judged. It gives you confidence and you can carry yourself in a cool way, but it’s not cocky. It’s a confidence that’s a godly confidence.” Bieber is arguably the biggest popstar on the planet, and he’s bold about his faith in Christ. He even recently led worship at a megachurch in LA, and later admitted to US entertainment site TMZ that doing so was more nerve-racking than performing at concerts.

In the rock arena, former Spock’s Beard multi-instrumentalist and singer Neal Morse is arguably the best role model. His exhilarating albums about God’s glory, his own testimony and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress– and this year a rock opera about Jesus – consistently excite even his many unchurched fans.

Stormzy’s explosive headlining set at Glastonbury this year was a landmark moment, and not just because he was the first British rapper to do so. It may be stretching a point, but you could say an artist with street credibility from a demographic often looked down on by the establishment, and creating authentic music that makes political points alongside blatantly Christian material, is actually echoing that original Larry Norman approach.

Most recently, Kanye West has shocked the world by releasing a gospel album entitled Jesus is King (Getting Out Our Dreams II/Def Jam Recordings). He’s also brought his ‘Sunday Service’ – an approximation of a worship service, including his faith-based tracks and covers of gospel songs – to Coachella, the first such performance to debut at a mainstream festival.

The future looks diverse – a mix of independents, major artists on labels and jobbing musicians networking. For musicians, as for the rest of us, if and when they let God lead, things can happen.

But the particularly low number of Christian bands and artists on recent summer festival listings suggests that CCM’s current focus of Sunday morning music (rather than Monday-to-Saturday) has resulted in young Christian musicians aspiring to lead worship, rather than impact the world around them, and the resulting lack of creativity suggests that the old saying, “Why should the devil have all the good music?” still applies.