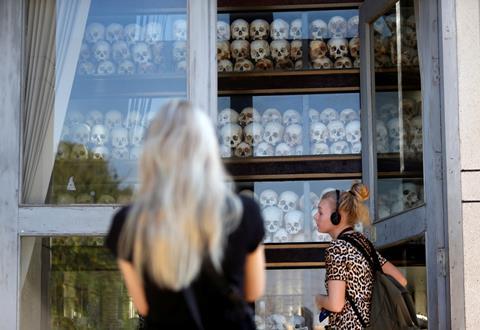

Today marks 50 years since the beginning of the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror, during which 1.3 million people were killed and buried in the Cambodian Killing Fields. In looking at the history, Julia Cameron unearths a shocking story of God’s lavish grace

Today marks a sombre anniversary. It’s 50 years since the fall of Cambodia to the brutal Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge army, so-called ‘Year Zero’.

Cambodia is enchanting in its culture and its contrasts. Angkor Wat temple alone was visited by 2.6 million tourists last year. But just below the surface is hidden a recent history beyond our imagining, for its peaceful pastures became ‘killing fields’ when Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge army turned the whole country into a nationwide ‘death camp’ in one of the most brutal regimes in modern history.

When Pol Pot captured Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975, its entire population was driven into the countryside — patients in hospital were pulled from their beds and pushed into the streets, even those with drips attached to their arms. There was no mercy.

The previous summer, a Cambodian student at Edinburgh University named Taing Chircc, sensed that a catastrophe was imminent. A Christian, Chircc pleaded for prayer from the Keswick Convention platform. No-one in the tent that night would ever forget his plea. Leaving his family safe in Scotland, he travelled back to Cambodia, knowing he would die. On his way back, he visited the headquarters of OMF International in Singapore, urging them to send in workers to baptise and teach the new Christians in Cambodia. Clearly it would be dangerous, and they might not come out alive. OMF senior leaders agreed to call for volunteers.

Five missionaries answered that call. One was Don Cormack, an Englishman. He delved straight away into studying the Khmer language, to be as useful as he could be.

Meanwhile, teenage soldiers were being recruited for Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge army, and brutalised, so they in turn could wield brutality. As soon as Phnom Penh fell, religious leaders, military leaders and intellectuals were rounded up to be killed. Some of the most gifted Cambodians were at that time studying in Western universities. They were recalled, with plausible invitations to help the new government; but on landing at Phnom Penh’s airport, they were driven straight to the nearest extermination centre.

Tens of thousands died in these extermination centres after being cruelly tortured. All such centres were overseen by Comrade Duch, Pol Pot’s chief executioner and ‘Grand Inquisitor’.

In his book Killing Fields, Living Fields (Dictum Press), Don Cormack recounts how, unawares, he met Duch in a border camp in 1979, after the Khmer Rouge had fled. Duch’s mother, a Christian, was dying. Hearing there was a church in the camp, Duch sent a boy to find Don. Don’s brief was made clear. “You believe in God. My mother is dying. She believes what you do. Talk with her.” In the few minutes Don was granted, he sought to bring comfort and hope to the woman. What pain she must have felt at her son’s evil. What prayers she must have prayed for him.

Some years later, The Far East Economic Review sent two journalists to hunt down Duch. By then he was a maths teacher in northwest Cambodia under an assumed name. His wife had been killed by bandits. The scoop appeared on 6 May, 1999. To the world’s surprise, Duch had become a Christian on Christmas Day, 1993 and been baptised in 1996. Duch remained faithful to Christ through his subsequent court trials, trusting in Christ’s death for his forgiveness, and asking the forgiveness of Cambodia’s people for his barbaric cruelty. “My story,” he reflected, “is like that of the Apostle Paul.” He died in prison in 2020 with a Bible and a hymnbook beside his bed. I can’t help thinking of his mother’s anguished prayers, believing against all hope. What utter, lavish grace of God.

Killing Fields, Living Fields engages one of the most insistent questions of the human heart. “Where is God in suffering?” The answer rings out clearly: he is right there with his people. The accounts given by survivors are, in the words of former IFES General Secretary Lindsay Brown “riveting, powerful, disturbing, even overwhelming.”

No comments yet