Why would a married couple trade their comfortable careers for a year of wild camping in Europe? Oliver R Moore-Howells explains how following Jesus turned him into an eleutheromaniac

Following a night of quiet despair about my life’s direction, my wife turned to me. “Let’s go for it,” she said, suggesting we finally embark on our long-held dream.

Now, it’s easy to admire Jesus Christ from afar; his rejection of materialism, conformity and the overbearing sense of control exerted by the society of his day. As Christians reading the Bible now, it’s easy to appreciate the many life-affirming messages of hope, joy and freedom that we find, while also dismissing them as idealistic or else a ‘calling’ intended only for a select few.

The book of Exodus is obsessed with freedom. Its very title means “a mass departure of people” – in this case, from a situation and a country in which they didn’t belong. Enslaved by a ruthless Pharaoh whose aim was to amass great material wealth by exploiting God’s people, we read that Moses was sent to deliver them from slavery – a condition that God certainly doesn’t want for his holy people.

FREE TO BE

Even today, Christ’s offer to set us free so that we may be “free indeed” (John 8:36) is seen by many not as a joyful emancipation from the spiritual and societal chains that shackle us, but as an invitation into an unknowable journey of sheer terror. After all, what might such freedom entail? And at what cost? “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom”, said Danish philosopher, Soren Kierkegaard, himself fully aware of the existential anxiety that accompanies dramatic life choices.

Many choices are ours alone to make. Like Peter stepping out of the boat, or the nomadic Abraham, very few of us are without some form of trepidation when it comes to taking that first step – even towards freedom. We catch ourselves thinking: What if I sink? Or get lost, far away from all I know and feel safe within? I can sympathise.

As a young Christian, I learned to read the Gospels as only applying to life after death. Almost everything Jesus said, it seemed, was about the hereafter rather than the present. Life was a trial run; a test to endure. As an adult, I see many of these verses rather differently: as an invitation to live the best life possible now and to make the most of it, as God intends. An advert run by Christian Aid declared most profoundly: “We believe in life before death.” I happen to believe Christ did too.

LIVING WATERS

In my life, I often find that the “rivers of living water” mentioned in John 7:38 or the “fountain of water springing up into everlasting life” (John 4:14, NKJV) have been conspicuously absent. Instead, my life has been full of worries about other people’s opinions of me, work duties, expectations and demands. Less a river of life than a river of sticky, toxic sludge that clogs everything up and narrows down my life into functions, roles and tasks. Eventually, the main organs start to suffer, and the body fails to operate as intended.

Weary of the kind of life I was living, like many, I found escapism in entertainment and books. Watching Ben Fogle’s New Lives in the Wild and reading John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley: In Search of America (Penguin Classics), I longed for the courage to strike out and do something adventurous; to escape the rat race. Many midweek mornings, shortly before getting up and following my usual paint-by numbers routine, I’d lie there, staring up at the ceiling, racking my brains for ways to give up work and find an alternative. Between getting older and hearing of people I’ve known die young, Christ’s advice to “take therefore no thought for the morrow” (Matthew 6:34, KJV) began to sound more urgently. The time comes where there is no tomorrow! The alarm bells ringing ever clearer then, I found myself gradually becoming an eleutheromaniac - developing a passionate mania for freedom.

I LONGED FOR THE COURAGE TO STRIKE OUT AND ESCAPE THE RAT RACE

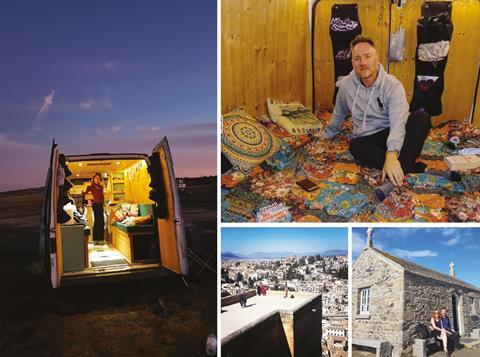

Meister Eckhart, the 13th-Century Christian mystic, once said: “And suddenly you know: it’s time to start something new and trust the magic of beginnings”, and so it was with us. This was our new beginning. Soon, thanks to my wife’s ‘go get ’em’ attitude, plans were put in place and ideas began to take shape. We moved into a shared house, saved and made arrangements with work (an agreed sabbatical and a notice of resignation tendered). We bought a converted campervan and readied ourselves to wild camp our way around Europe.

There was no doubt: we needed this. I needed to escape my lacklustre, process-driven role as an assistant manager in a call centre; my wife from the stress of high caseloads and encroaching compassion-fatigue working for a children’s charity. The words of GK Chesterton rang in our ears: “A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.”

A REVOLUTIONARY LIFE

Now, upping sticks to go travelling is hardly a revolutionary idea. Young people do it all the time. But when you’re approaching 40 years of age and embedded in a life of routine and responsibility, choosing to hack away at the ball and chain that society expects you to haul behind you becomes increasingly difficult. What will people think? Isn’t it time we grew up, got a mortgage and doubled-down on our efforts to build our pension pots? Our natural inclination is often to conform, save face or please others. And while we did have support, and were sent off with blessings from many quarters, not all were encouraging. Whether out of fear for our physical safety or future financial security, or whether out of a sense of betrayal for not following their preferred life path, some simply couldn’t understand our decision. Yet the question had to be asked: How safe and secure are we anyway? (None of us could have predicted, at that point in time, that a worldwide pandemic was around the corner that would take thousands of lives, destroy businesses, confine us to our homes and irrevocably change our lives forever.)

Before the time came to leave, I had numerous conversations with people and observed slowly shifting attitudes in society. Some were already rejecting the norm of steady careers, marriage and children. Even those who weren’t played the lottery or invested in the hopes of reaching financial freedom. It’s little wonder we’re obsessed with Who Wants to be a Millionaire, X Factor and the many other get-rich and/or famous quick reality TV shows. People want out; a shortcut to a more fulfilling life. Unfortunately, that’s rarely how it works. Instead, we try the ‘do it yourself’ punk ethic of finding alternatives. Whether it’s taking on jobs that offer agile working, freelancing or else living in a van in order to save, people want something more.

NEW KINDS OF FREEDOM

Christ chose the roaming, nomadic life himself. He could even be said to have been homeless. “Foxes have dens and birds have nests, but the Son of Man has no place to lay his head”, he says in Matthew 8:20, perhaps caught between security and freedom. Rejecting the baggage of taking on the unnecessary responsibilities of his day, it’s not surprising he could say: “learn from me…For my yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:29-30). Of course, very few can, or could, tolerate such a message. Security and ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ is just too tempting. Little wonder so many lives end up in nervous breakdowns, toxic relationships, divorce, alcohol and/or drug dependency, bitterness and suicide. “For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it” (Matthew 7:13-14).

Recognising that physical freedom alone was not enough, my wife and I sought to pay attention to our spiritual needs too. Whether attending a church service en route, such as the one in Abbotsbury where it was just us and the vicar, or one in Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, France, where we partook in a packed Christmas carol service, we got involved. Given the great gift of time and silence afforded us, we also made efforts to read, pray and meditate. Learning to quickly forgive also came into play; after all, sharing the limited space of a campervan and being together all the time held its own challenges although, ultimately, it strengthened our relationship.

Being on the road, sightseeing, learning a language and meeting with interesting characters was truly a liberating experience. Before long, however, we recognised the need to find work for our idle hands. Volunteering to work with a family in Normandy, and another in Auray, in exchange for board and lodging, was most welcome. We did gardening, built a treehouse, walked dogs and renovated a garage for a family Christmas party. Work became enjoyable, creative and challenging, and was a departure from the norm. We had ready access to a toilet and shower too!

CHRIST CHOSE THE ROAMING, NOMADIC LIFE HIMSELF

It’s fair to say that embracing some of the ideals contained in the Gospels has transformed our lives. It taught us valuable lessons and allowed us to address our deepest human needs. Visiting parts of Britain, Belgium, Netherlands, France, Spain and Portugal were a blast too! However, if there’s one thing that we’ll take away from the experience, it’s that there is, as it says in Ecclesiastes 3:1, “a season for everything” (CEB).

Travelling, for us, was a part of discovering what it means to be truly free. But while outer, physical, freedom should not be neglected, God also wants inner, spiritual freedom for us too. Because without it, physical freedom can quickly lose its allure