Sport unites like little else, says Dr Dan Strange. Our readiness to compare stadiums to cathedrals and pitches to altars offers Christians a unique opportunity to share their faith

The father of the modern Olympic Games took his sport very seriously. “For me sport was a religion…with religious sentiment”, wrote Pierre de Coubertin in Olympic Memoirs (Comite International Olympique).

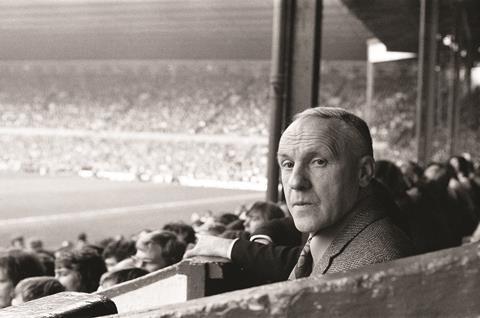

Strong words. But perhaps we’re more comfortable with the tongue-in-cheek comment made by former Liverpool FC football manager Bill Shankly: “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.”

Sport is important, but can it really be called a religion?

In answering the question, the problem isn’t with ‘sport’, but with ‘religion’. Among scholars and even at street level, defining religion is notoriously difficult. As the academic Paul Griffiths puts it, when it comes to talking about religion: “hardly anyone has any idea what they are talking about or, perhaps more accurately, there are so many different ideas in play [that it makes] the difficulties in communication at the Tower of Babel seem minor.”

So we need to define our terms. And, spoiler alert, in my definition of religion, yes, sport can be both religious and a religion in a way which is relevant to our Christian discipleship, witness and evangelism. Let me explain.

Hide-and-seek

In Romans 1:18-23, the apostle Paul describes a cosmic game of hide-and-seek between God and humanity. Although we may have been told that God is hiding, in reality he has made himself known, dynamically and personally, in everything he has made, and that includes us, his image bearers.

Tragically, knowing our guilt and shame in having bitten the hand that feeds us, our reaction as creatures is to hide from our creator. We suppress the truth and try to drown it, and with that comes a substitution: we seek to replace our creator with all kinds of created things. This process makes up what we might call humanity’s ‘religious consciousness’. We are God’s image bearers built for worship, and yet we have rebelled against the only one worthy of worship. We know God and so are without excuse, but we are ignorant of him. We are running to him and running away from him at the same time. This is the dignity and depravity of our humanity. This messy mix is what I believe Paul is getting at in Acts 17:16-33 when he calls the Athenians “very religious” and at the same time points to their unknown God. He’s not commending their worship (he also says he is “greatly distressed” by their ignorance, and calls them to repentance) yet he recognises their need to worship something.

What does this religious consciousness look like? We can unpack it by thinking about ‘magnetic points’ to which we are irresistibly drawn. They are the questions of our existence that we answer, often not consciously, but in the way we live our everyday lives. They are itches that we just can’t stop scratching. And for many of us, sport can be that scratch.

The magnetic points

The first magnetic point which describes our religious consciousness is ‘totality’ – is there a way to find connection? This is the suppressed truth of knowing that we are dependent creatures.

We often feel small and insignificant with no sense of identity. And yet when we connect with something or someone bigger, we find significance through belonging, and enjoy communal awareness. We crave connection, feel abandoned after we’ve experienced it and crave it again and again.

The more we look to sport for ultimate answers, the more it starts to look religious

Nelson Mandela once famously said: “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.” Eight of the top ten most watched TV programmes last year were sport. This year, with the Euros and the Olympics, it may well be ten. Sport unites like little else. Any fan knows that sense of connection and togetherness.

The incredible sense of community created by sport can be seen in documentaries such as Welcome to Wrexham. These reality TV programmes are popular because they focus on something bigger than just the performance. I witness this every Saturday morning as I lumber around my local parkrun.

Playing in a team also offers something more than playing by yourself. Michael Jordan, the most famous basketball player of all time, recognised that he couldn’t play without his team, especially his great friend Scottie Pippen. In the Netflix docuseries The Last Dance, he said: “I didn’t win without Scottie Pippen, and that’s why I consider him my best teammate of all time. He helped me so much in the way I approached the game, in the way I played the game. Whenever they speak Michael Jordan, they should speak Scottie Pippen.” Even healthy competition where opponents strive together for excellence, rather than just trampling on the other, displays this connection.

The second magnetic point is ‘norm’ – is there a right way to live? This is the suppressed truth of knowing that we are accountable creatures.

We have a vague sense there are rules to be obeyed. This brings with it a sense of responsibility to live up to those norms. Every fan will know the unwritten dos and don’ts of supporting their team. And please don’t get me started on what has become the philosophical discussions surrounding VAR in football!

Fairness in sport is a massive topic, most controversially surrounding trans-inclusion, where fairness comes into conflict with safety and inclusion. These are deep questions; dare I say, religious ones.

The third magnetic point is ‘deliverance’ – is there a way out? This is the suppressed truth of knowing that there is something wrong with the world. There is finitude, brokenness and wrongdoing, and the problem of suffering and death consistently confronts us. We long for the glory days and deliverance from these evils – we crave redemption. And yet we can’t agree on what our ultimate problem is, let alone whether there is a solution.

Of course, sport could be viewed simply as an entertaining diversion and distraction from thinking about such things. But it’s never simply that. Those who compete in sport often ask questions such as: “Why do I sometimes feel rubbish even when I win?” or: “Why does injury affect me so much?” At an elite level, this only intensifies.

When we connect with something or someone bigger we find significance through belonging

This summer, 92 per cent of Olympians will return with no medal. Most will ‘fail’. In times of disappointment, which sport provides in abundance, we end up asking broader existential questions. Reflecting on his own mental health struggles in an interview with The Guardian, England rugby star Jonny Wilkinson summed it up like this: “It feels as if I spent years trying to fight depression with another Six Nations Championship, or some more caps, or titles, or points. ‘Surely,’ I told myself, ‘that will keep you off my back?’ It doesn’t. It’s never enough.”

Retirement, which comes relatively early in life for athletes, is often referred to as a ‘first death’. Sports reporter David Coverdale explains that a large number of medal-winning British athletes have “opened up about their struggles with depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts since quitting and many have raised concerns about the lack of aftercare offered by governing bodies when they come off UK Sport funding”. He writes that Olympians feel “a loss of identity and purpose when they finish because of the all-encompassing nature of their career and the comedown from having been among the world’s best in their chosen field”.

The fourth magnetic point is ‘destiny’ – is there a way we can exercise control? This is the surpressed knowledge that, although we know ourselves to be active players in the world, there is a nagging feeling that we are also passive participants in somebody else’s. Sometimes we feel confident that we are masters of our destiny. At other times, we feel trapped, with no agency.

If you spend any time around sportspeople, you will know that many are deeply superstitious. This is all about control – while recognising the paradox that sport at its best is unscripted and not controlled. In an article for ESPN, Indian sports psychologist Ashis Nandy writes about why cricketers are especially superstitious. In a game that has a high degree of variability, it is inevitable that players will turn to superstition to help regain a sense of control, he says: “No wonder cricketers lean on superstition as a crutch. They cannot accept the awful truth – that the game is governed by erratic umpiring decisions, random tosses and unpredictable seam movement – so they invent a coping strategy to persuade themselves they are in control.”

The final magnetic point is where all the others converge – ‘a higher power’. Is there something beyond that which we see? This is the suppressed truth of knowing that behind all reality stands a great reality. The deeper we look to find connection, discover the norm, search for deliverance and try to control our destiny, the more we come to questions of a higher power. But what and who is it?

The more we look to sport for ultimate answers to these questions, the more it starts to sound, smell and feel religious. Scrambling for language to articulate what’s going on, and despite calling ourselves post-Christian, we latch onto our cultural heritage - in which Christianity has played a massive role. So we start comparing stadiums to cathedrals, pitches to altars, statues to shrines, chants to hymns, and those increasing moments of silence or applause (when we remember the lost or a legacy) to a service. “Are you going to church this weekend?” is a common way for football fans to ask others if they will be at the match.

Promotion and relegation

Humanity’s hard-wired religious consciousness has to come out somewhere. So sport can and does function religiously as it attempts to answer the questions posed by the magnetic points. The problem, of course, is that ultimately it can’t. For all the benefits it offers, we don’t have to look hard to find a dark underbelly of disconnection, conflicting norms, false deliverances and irrational superstition in the world of sport. A recent study showed that reports of domestic abuse increased by 38 per cent when the English football team lose and 26 per cent when they win or draw. Maybe it’s not such a beautiful game after all.

In times of disappointment, which sport provides in abundance, we end up asking broader existential questions

As Nick Hornby reflects in Fever Pitch (Penguin): “As I get older, the tyranny that football exerts over my life, and therefore over the lives of people around me, is less reasonable and less attractive.” The tragedy is that we’ve taken what is a good gift of God and promoted it to a level far beyond its competency. And in doing so, we’ve relegated the God of the universe, the one who gave us this wonderful gift. It can only end in tears.

But there is good news. First, many of us desire to share the gospel with our friends, but are disillusioned as we struggle to find traction without that awful conversational crunch of gears:

Friend: “We’ve just scored.”

Me: “Jesus scored a goal for us all…”

However, looking at sport through the lens of the magnetic points recognises that our friends are asking – and attempting to answer – religious questions whether they know it or not. These may be conversational ways into the gospel. One friend recently told me that the question of superstition in sport has been one of his most successful ways into a faith conversation.

Second, the gospel is good news. It’s only in Jesus Christ that we find true connection, norm, deliverance and destiny, for Jesus is the higher power, the word made flesh. Where sport functions as a religion for some (and as Christians battle sin, that can include us!), our task is to lovingly and patiently invite people to stop and think, exposing the lies we tell about sport when it becomes a matter of ultimate importance, and calling people to instead put their trust in Jesus Christ – the beautiful name.

Then, in its right place, reframed and reordered, we can truly enjoy the blessing that is sport.

No comments yet