Dr Sara Schumacher says the UK Church is experiencing a renaissance of art within its walls

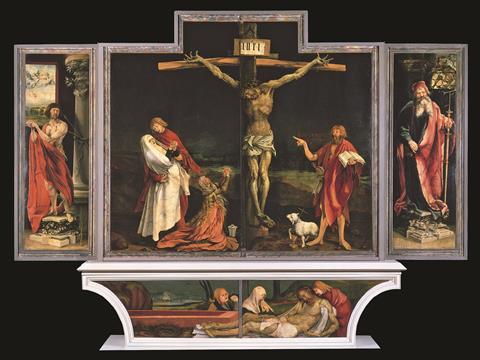

For most of the Western Church’s history, visual art has been central to its practice and life. Exteriors and interiors of holy places were often covered with images that held the Christian story. These images formed and shaped the theological imagination of those who passed in and out of the spaces. These works of art, such as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling or Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, were not mere decoration, but active objects created with a purpose.

The Reformation disrupted the Western Church’s relationship to image. For theological and historical reasons, forms of Protestantism emerged that were suspicious of the image’s power and feared its pull towards idolatry. As these fears and suspicions took root, this led to, at one end, acts of destruction and, on the other, apathy and disinterest. Artists, needing to make a living but also desiring to use their gifts, eventually gravitated away from the Church and found their patronage support in the monarchy (think Louis’ Versailles), the merchant classes (Dutch still life and English portraiture) and eventually the art market (where we find ourselves now).

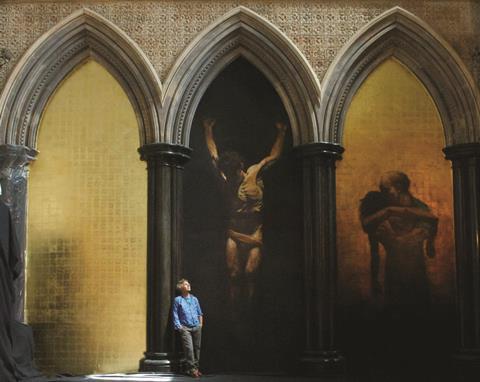

After the second world war, Britain saw the beginnings of a restoration in the relationship between the Church and the artist. By some, the arts were believed to be central to the renewal of a broken society and visionary clergy, such as Walter Hussey at St Matthew’s, Northampton, took hold of this sentiment and translated it into acts of arts patronage. Two decades into the 21st century, it’s not hyperbolic to suggest that the UK Church is in a renaissance of art within its walls, a phenomenon seen in the largest of cathedrals as well as in local parish churches. At one end, we’ve seen the installation of Tracey Emin’s For You in Liverpool Cathedral, while at the other, we have Charlie Mackesy’s Triptych in St Paul’s, Hammersmith.

Today, church leaders are more convinced about the power and potential contribution art has to make. With this enthusiasm comes a desire to rebuild the relationship between the Church and the artist. While this is an important aim, any rebuilding needs to be done with an awareness of foundations. This means that we, as a Church, need to face the implications that emerge from rebuilding on top of a historic break in the relationship. We need to be aware that this rupture impacts both the church leader and the artist. On one hand, leaders can feel ill-equipped to know how to cultivate artistic creativity within their church communities and buildings. On the other, artists can feel at a loss about how to bring their artistic gift meaningfully into the life of the Church.

So, in light of this challenging history, how do we move forward? I want to offer three starting points for rebuilding a flourishing relationship between Church and artist so that artistic creativity is cultivated. Each will need to be contextualised for particular traditions, but all can be the beginnings of something new and exciting.

Trust, not suspicion

Starting point one: Artistic creativity needs trust to flourish. It withers in a culture of suspicion. As anyone who has done home renovation knows, what’s hard about rebuilding is that you don’t get a clean slate. A historical foundation already exists and this is the place upon which new structures are established. Put another way, as we seek to rebuild the relationship between the artist and the Church, we do not get the luxury of doing so in an abstract, ideal vacuum.

In some Protestant traditions, the visual has been so closely linked to idolatry that visual art was banned from the church space. Any image of God – mental or physical – was forbidden: the risk of a false image of God was not worth what an image might positively offer. Combine this with an elevation of the word and ear over and against the eye and image and you cultivate an imagination that is trained to be suspicious (and afraid) of the visual and its power. We might say we are fully on board with the incorporation of art into the life of the Church (which is a good thing) but we would be naive to do so without being aware of the beliefs that mark our past. To use another metaphor, as we plant seeds of art into the Church’s life, is the quality of the soil sufficient for it to take root, grow and flourish?

As we try new things, give artists space to create and bring work into the Church’s worship, we will discover where the historic suspicion still lies. With our eyes on the goal of rebuilding, we also have to be alert to this suspicion that will lie dormant until engagement happens. And this will be true for both artists and church leaders. For the latter, they might have had their theological imagination formed by a confidence in the word but a fear of the image. For the artist, their imagination has also been cultivated by a narrative, one that has often said the Christian faith is against their gift or that faith and art are best kept separate. For both artists and leaders, we should expect practice to reveal these suspicions. And when they do, rather than see them as a sign of failure, they can be seen as an opportunity for restoration. For Christians, we have a framework of repentance and forgiveness that allows us to move beyond the past and cultivate a faithful way forward. In this rebuilding, repentance goes in both directions: the artist and the church leader both being attentive to the part they have played in the brokenness. As this happens, a culture of trust between Church and artist can begin to grow. And this is vital, for trust is needed for artistic creativity to flourish.

The Church is not a museum or a gallery. It does not exist for the work of art

Where there is trust, there is curiosity and the ability to ask questions marked by empathy rather than defensiveness. Curiosity leads to deeper understanding, and it is from this place that church leaders can enter into a dialogue with artists to help them understand the theological significance of the space and how the work fits within this. This type of collaboration has the potential to release the artistic gift, with the resulting work being something fitting for the space, the congregation and the worshipping tradition of the church where it is installed. This type of artist-church leader relationship sits behind Alison Watt’s Still, a painting installed in the Memorial Chapel of Old St Paul’s, Edinburgh. The artist was inspired by the space, which started a conversation with the rector, who was willing to receive her inspiration and trust the work that came to be. His trust was demonstrated by participating in the creation of the work as a theological guide, helping the artist to ‘see’ the parameters within which she was working while, at the same time, giving her freedom to use her gift. While in this example, trust enables artistic creativity to flourish within parameters, we need to be attentive to where historic suspicion leads us to use those same parameters to control. Without being alert to the reality of our theological and Church history, our rebuilding risks crushing the gift of the artists within our midst.

Where does it come from?

Starting point two: Artistic creativity is a gift, not a download. It’s easy to think that artistic creativity is given as a fully formed entity. We like to think of inspiration as some sort of lightning bolt from heaven – this is why we are drawn to stories of prodigies, who seemingly master their craft with little effort. However, for most people, artistry begins as the small seed of a gift that needs cultivation. And in order to cultivate this gift, artists need space, time and opportunity to practise. This means that, as leaders, we cannot expect the finished product at the beginning of the artistic process. It means considering how we create psychological and creative safety for artists to be vulnerable in creating, and also in offering their creation to the gaze of others. It means inviting the gift of the artist into the life of the Church, while having the courage to discern when one’s gifting might not be in the arts.

In Art Needs No Justification (Regent College Publishing), Hans Rookmaaker suggests that: “Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians (12:12-27) speaks about the Christian community as the body of Christ. Each has his specific function therein. And not one can be left out. Certainly some play the music, draw the likenesses, photograph the movements and write the stories. These are the artists. They have their rightful place in the family of God.” This perspective increases the urgency for our rebuilding project. If artists have a “rightful place”, then re-establishing a relationship between Church and artist becomes a necessity rather than an optional extra. Church leaders are now responsible to God for making space in the life of the Church for the exercising of the artist’s gift. However, understood in the context of 1 Corinthians, the responsibility does not lie only with the church leader. Rather than building up of the self, the gifts given in 1 Corinthians are for the “the common good” of the body of Christ (12:7). Thus, the exercising of the artistic gift is not about an artist’s career (although that might be furthered); instead, it is about serving the other. It’s about a particular community who will receive the gift of the artist’s creativity.

With this perspective, we are reminded of something that is easy to forget as we seek to rebuild: the Church is not a museum or a gallery. This means it does not exist for the work of art. When a work of art comes into a church space, it becomes subsumed into the purposes of the space. Seeing it this way not only shifts our frame of reference but also requires us to cultivate discernment to be able to ‘see’ what art is fitting within a particular space and for a particular community. However, as we discern, we do so trusting that the gift of artistic creativity has the potential to lead to the fullest expressions of human creativity, building up the body to be more like Christ. That end should guide both the artist and the church leader in practice.

Taking our time

Starting point three: Cultivate patience. Rebuilding the chasm left by a 500-year disruption takes time. We need patience to allow hearts to change as suspicions emerge. We need patience as we revisit our theology and the convictions that have led us to conclude particular things about the visual. We need patience as we introduce our congregations to work that is unfamiliar, intimidating or uncomfortable. Patience allows real change to occur. As the visual is brought back into the Church space, time is required to stretch the imagination of those who are in the Church, so they can receive the gift of the work well. This requires a church leader to consider how they will help prepare a congregation to receive a work, especially if engagement with art is a new experience.

Artistic creativity needs trust to flourish. It withers in a culture of suspicion

Intentionally cultivating patience is important because impatience can come with enthusiasm. When we rediscover something that was lost, we can feel the urgency to rectify the situation right now. Or when we have become convinced – either by conviction or by gifting – that art has something vital to contribute to Church life, impatience can come when others don’t see things the same way. This is the beauty and challenge of Christian community – we don’t have the option to leave someone behind. Instead, we must bring people along so they can see, experience and hear art in new and constructive ways.

This includes celebrating the baby steps forward rather than lamenting that we have yet to return to the ‘golden’ age of art in the Church. We must listen to those who have concerns or who simply do not yet understand. When we do this, we allow the community to be a part of discerning what art is fitting for the congregation at that particular time, for it will be their theological imaginations that will be formed and shaped by what their eyes alight upon.

No comments yet