With a surge in interest in spiritual formation, ancient paths and prayer rituals, Celtic Christianity is enjoying a moment. Richard Roberts shares the fascinating tale of the first missionaries to these shores

Today, despite the increasing secularisation of our society, we take for granted that Christianity is embedded in significant parts of our culture and establishment – from the Royal Family and Lords Spiritual, to the basis of our moral code and laws. But what are the origins of Christianity in Britain?

The Romans were the first to bring the good news of Jesus to British shores. But initially, Christianity was regarded with suspicion and, in the third century, the first British Christian martyr, St Alban, was put to death by Roman soldiers, possibly for sheltering a priest fleeing persecution. This was followed by the deaths of two martyrs in the fourth century at Caerleon, Wales. In 312 AD, the emperor Constantine claimed to have been converted and in 313, an edict was issued proclaiming tolerance for all religions. Eventually, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, including Britain. But while Christianity dominated the private and public life of wealthier Romano-British citizens (genetically Britons but culturally Roman), paganism retained a foothold in the more rural areas, where Druids offered sacrifices to Celtic deities at springs and other sacred sites.

By the 390s, Roman legions had begun to withdraw from Britain and Angles, Jutes and Saxons took advantage of the power vacuum. In central and southern Britain, Anglo-Saxon paganism was very much on the resurgence. This was a time of upheaval for the peoples in Britain, with the Church gradually becoming confined to the western fringes such as Wales, Cornwall and Strathclyde in the north-west. These regions, along with Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and parts of France, spoke various Celtic languages and, because of sea trading, the Celts were in much closer contact with one another than we might have thought.

Christianity flourished in Wales at this time and the fifth and sixth centuries became known as ‘the Age of the Saints’. One early Welsh saint, Illtud, established the earliest recorded school of learning in Britain at his monastic centre at Llantwit Major. David, now the patron saint of Wales, was a bishop and missionary who travelled widely throughout Wales and into England, visiting, among many other places, Glastonbury in Somerset. David, who died 589, is said to have founded twelve monasteries in which monks lived under a harsh routine. Christianity in the Celtic regions was heavily dependent on the formation of such monasteries, with very little emphasis on cathedrals as the seat of bishops, as evidenced elsewhere in Europe.

As described by Ian Bradley in Colonies of Heaven (Darton, Longman & Todd) Celtic monks regarded their monastery as an outpost, or colony, of heaven; a foretaste of God’s kingdom on earth and the very place where God dwelled. Monasteries served many functions – most notably as centres for study and places of refuge and hospitality for travellers. The name of their guest houses in Latin, hospitium, gives rise to our word ‘hospital’. Their approach to mission was holistic, encompassing both spiritual and practical needs, with monks exhibiting huge generosity towards strangers. While monks would eat frugal ‘peasant’ meals, they provided guests with sumptuous fare.

Monasteries also acted as missional bases for evangelism and church planting. Today there is much interest in learning from the Celtic spirituality of these early monasteries, especially their rhythms of prayer, silence and other devotional practices, but their emphasis on mission is sometimes overlooked.

The making of a missionary

Irish saints played a significant role in the evangelisation of the British Isles, particularly in Scotland and northern Britain. Yet at the turn of the fifth century, Ireland was a forbidding and wild land, ruled by fierce pagan warrior-kings and powerful druid advisors. This was about to change.

Around 390, a young man named Patricius was born. St Patrick, as we now know him, came from a well-to-do Christian family, possibly living in Wales, a location vulnerable to pirate raiders. Aged 16, he was violently abducted from his family estate and sold into slavery in Ireland. Patrick was put to work herding sheep and pigs on the wild Atlantic coast of County Mayo, an unexpected and unlikely occupation for someone of his social standing and status.

There is much interest in learning from the Celtic spirituality of early monasteries, but their emphasis on mission is sometimes overlooked

Patrick had been raised in the Roman Church but had not taken his faith very seriously. The experience of slavery plunged him into great uncertainty, yet this deeply upsetting experience ignited a deep faith in God which formed the basis of his future ministry. In his Confession (Bantam Doubleday Dell), he recorded that “in one day I would pray up to 100 times, and at night perhaps the same”. After six years of this intense devotion, God revealed to Patrick in a dream that a ship had been prepared for him to release him from captivity. Patrick made his way towards the specific port, directed by the Holy Spirit. He escaped, but later returned voluntarily to Ireland as a missionary bishop.

In north-west Ireland, he saw thousands of former pagans come to faith and be baptised. Patrick trained and ordained priests to look after his new converts, enabling him to move on to new communities. Today, we would describe him as a church planter whose method was to appoint and empower indigenous leaders. He derived much joy from the fact that so many became monks and “virgins of Christ” (or nuns) although these were mainly solitary monastics who lived separately, rather than those who formed monasteries.

Reverse mission

Fast forward a century or two, and Ireland had become one of the great powerhouses of Christianity, particularly through the influence of monasteries, with their emphasis on the practice of mission. Patrick and others had gone to Ireland as missionaries and, in the centuries following, Irish monks set out for the British Isles in what is now described as ‘reverse mission’.

Columba was among the most influential Irish missionaries to Scotland and, like many Celtic saints, was of noble birth. He founded a number of churches and monasteries which formed the so-called ‘Columban Church’. Having established a monastery at Derry, he left Ireland in 563 aged 42, founding a monastery on Iona, an island in the Inner Hebrides. The Celtic concept of pilgrimage – or peregrination – was not so much a short-term journey to find God at a sacred place, but more a permanent exile; an expedition to carry God’s presence and establish new outposts of the kingdom. Like many others, Columba demonstrated this willingness to missional journeying, leaving behind all that was dear in order to fulfil God’s call.

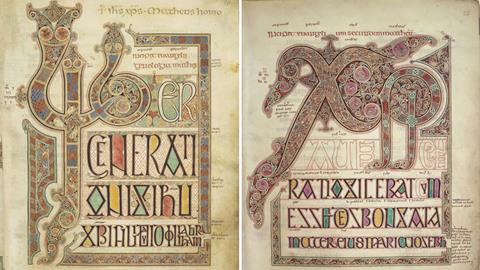

Columba’s new base in western Scotland was part of the same Gaelic kingdom as that of Northern Ireland (only twelve miles of ocean separated the two regions) and, consequently, he acted as both diplomat and missionary. Some viewed him as more of a soldier and politician than a monk since, for example, he visited the Pictish king in Inverness. He is also credited with conducting the first-ever recorded ceremony of anointing a king in western Europe, along the lines of the Old Testament examples. Columba was a notable scholar, said to be copying a manuscript of the Psalms when he died in 597.

Columba was a complex character with marked inconsistencies. He is remembered as standing in the ocean with arms raised praying – but on at least one occasion this was to implore God to cause a sinful man to drown! This image captures the essence of paradox in the lives of Celtic saints as well as, of course, in our own.

Like other missionary monks of his time, Columba was steeped in an Irish monasticism that was particularly severe and went on to found further monasteries in Scotland and Britain with equally austere routines. The Celtic Christian worldview was focused on spiritual battle and they took discipleship extremely seriously. This included approaches to spiritual life that may now be regarded as unnecessarily harsh, including dietary restrictions and self-imposed hardships. The commonest form of literature surviving from this time are penitentials, which list the required penances for specific sins. Columba’s teacher, Finnian of Clonard, codified various transgressions with, for example, ‘evil thoughts’ necessitating the discipline of prayer and fasting, while a church leader who committed murder was subject to ten years’ exile and required to make restitution to the victim’s family.

Penitentials can be viewed either as extreme legalism or, alternatively, as providing hope, a way forward and a cure for even the most awful of sins (Finnian stated that forgiveness was granted immediately on repentance). But however we now regard such practices, in an age where the pursuit of pleasure and leisure are held so highly, we can certainly learn from the seriousness with which Irish monastics approached spiritual life.

One of the most important monasteries of this time was Lindisfarne, a tidal island on the north-east coast of England. In response to a request from the Northumbrian king that a monk from Iona be sent to his kingdom, Aidan established a monastery that, in due course, became a centre of mission for the entire region.

Despite the surrounding society being strongly patriarchal, there were several female-led monasteries in Northumbria. Learning under Aidan of Lindisfarne, in 657, Hilda established an abbey at Whitby which became a centre of learning. She was following in the footsteps of Brigit of Kildare, who similarly led a mixed Celtic monastery. Hilda was reputed to have trained several future leaders of the Church and in his Ecclesiastical History of the Church, Anglo-Saxon historian Bede recounted: “So great was her prudence that not only ordinary people but kings and princes sought and received her counsel when in difficulties.” In addition, Caedmon, a notable musician who became known as the Bard of Christ, was nurtured at Whitby under Hilda’s leadership.

The Celtic Church

When speaking about ‘the Celtic Church’ we should remember that we are dealing with Christians who spoke several different Celtic languages and whose churches and monasteries spanned many centuries – there was certainly never one monolithic Celtic Church.

In 595, Pope Gregory sent Augustine (not to be confused with Augustine of Hippo) to lead a mission to evangelise England and he became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Following the success of his mission, it was inevitable that there would be contact between the so-called ‘Roman Church’ and those on the Celtic fringes. The fact that the two bodies hammered out their variations in practice at the Synod of Whitby (664) indicates that they considered themselves to be part of the same universal Church rather than separate denominations.

Celtic Christians emphasised God’s presence in the natural world and especially the ‘thin places’ where the reality of the unseen realm seems more easily discernible. Another feature, particularly of Irish monasticism, is that it relied heavily on a tribal system of organisation. Hence churches and monasteries such as Iona favoured local leadership of abbots and abbesses, with less emphasis on the more centralised system of bishops and archbishops that was prominent elsewhere. It could be that such localism even today is key to the Church’s mission in the UK.

There is a danger that the notion of ‘Celtic Christianity’ can become a projection of our desire to create a fictional, idealised Church

There is, however, a danger that this notion of ‘Celtic Christianity’ can become a projection of our desire to create a fictional, idealised Church to which we aspire. Myths abound, such as the idea that it was a non-authoritarian and free-flowing Church, when in reality, Celtic monasteries were very strongly hierarchical. In addition, although there is evidence that Celtic evangelists adopted pagan sites and ‘Christianised’ them, they certainly did not blend Christianity with paganism. There is no doubt that they sought clear conversion from other belief systems to make disciples for Jesus.

Theirs was a commitment to radical obedience, including the idea of peregrination, and the missional effectiveness of Celtic monks and nuns was founded upon rigorous rhythms of prayer, reciting the Psalms and various forms of self-denial, as well as sacrificial hospitality, generosity and the painstaking learning and copying out of scripture. Such practices, which many are re-emphasising today, resulted in the sort of personal spiritual formation and resilience required for effective mission – both then and now.

1 Reader's comment