With each swipe of a screen producing another distraction, Chris Witherall explores the concept of Popcorn Brain. Is the fast-pace of modern life inhibiting our ability to deepen our faith and cultivate a more meaningful relationship with God?

I’ve had something of a neurological complaint recently. It’s annoying, but thankfully it isn’t serious. Recently, my brain has felt itchy.

I’m speaking figuratively, of course - I’m told that there are no nerve endings running through my grey matter - but the itch has felt very real.

On occasion, it’s been maddening that I can’t simply pop my skull open and have a good scratch. I was trying to get to the bottom of this sensation, when an email arrived in my inbox explaining everything. I was working hard that morning (by which, I mean flicking distractedly between social media apps), and it took exactly zero seconds to abandon my toil and open the message. I usually ignore this type of digital missive, but I was intrigued by a clinical - and frankly painful - sounding term, which I hadn’t heard of before.

This term was ‘popcorn brain’.

Popcorn brain may sound like a snack beloved by zombies everywhere, but I’ve discovered otherwise. I’d like to tell you about it and examine the implications for our faith. I think there are a few.

What Is Popcorn Brain?

The term ‘popcorn brain’ was coined in 2011 by David Levy, at the University of Washington. It describes the apparent impact of modern technology on our brains, as we’re encouraged to flick rapidly between multiple applications and activities. Levy suspected that the online world had become so stimulating and fast-paced, that it was causing us to find the ‘real world’ boring and hard to process. In recent years, an increasing number of academics and researchers are weighing in on the issue. One such person is Dr Gloria Mark at the University of California, whose recent book Attention Span suggests that our ability to focus has dwindled from around two and half minutes, to about 47 seconds, in the last two decades.

According to Mark, once the attention span has been diverted, it takes around 25 minutes to get back on track; and that we frequently switch onto new tasks, instead of returning to the initial one. We start on one activity and end up juggling four - or more! There are suggestions that many popular corners of the internet are developed to be addictive.

Johann Hari’s 2022 bestselling book Stolen Focus picks up on these themes and runs with them. Hari discusses the acceleration of offline and online information over decades and suggests that it’s overwhelming our brains.

Amidst infinite video streams, click-bait ridden headlines, and dating apps which present far more people than we could meet in a month of coffees, many of us sense the struggle. Popcorn brain isn’t linked only to technology, either. In his book The Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz documents the dizzying number of decisions that we make in modern life and explores the potentially negative impact. As a musician, I’ve seen the way in which new music has become increasingly shortened to fit in with radio play requirements. Perhaps you’ve spotted ways in which your own corner of the world has accelerated and grown louder. It seems at least plausible to suggest that modern society is now more distracting than ever.

Is Popcorn Brain real?

A theory isn’t true just because it has a fun name and a certain plausibility about it. Among all the nervousness, there has been some pushback. Critics point out that the conversation around focus is still relatively young. A lot of the developments which characterise modern life are still only a decade or two old.

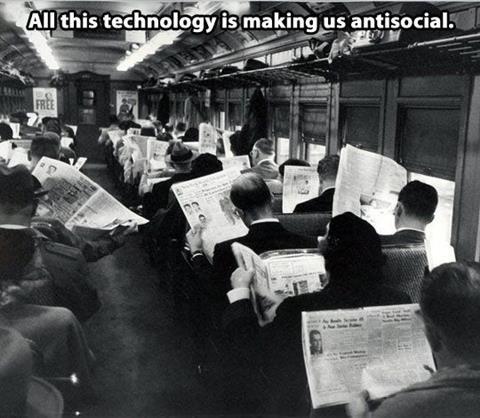

Popcorn brain skeptics are reluctant to get carried away, because change doesn’t always equal decline. A popular historic photo shared online shows an old-fashioned train full of people ignoring each other and reading newspapers. It’s often shared with a caption such as, “Next time you hear someone say technology is making us anti-social, show them this picture”.

By way of reply, we might point out that broadsheets aren’t very portable, they don’t update with real-time news, and they certainly don’t display cat videos! Hysteria around social change is nothing new (Socrates was complaining about teen culture trends back in 6 BC), but as developments go, the recent years have been transformative.

The faith implications

Aside from the truth of the gospel, the only universally held Christian position seems to be that Graham Kendrick and rich tea biscuits are failsafe. So there will be disagreement among Christians. But I do think popcorn brain is worth taking seriously though, for four reasons.

1. The call to listen

Scripture shows us that God speaks, and that we’re called to listen. In Isaiah 55:2-3 God says:

“Listen diligently to me… incline your ear and come to me; hear, that your soul may live…”. In Psalm 46:10, he tells us “Be still and know that I am God.”

We’re called to cultivate an intentional relationship with our heavenly father, and this is often fostered within calm, focused attention. Meditating on God’s word is no different. Speaking on Proverbs, Tim Keller once remarked that it’s “the hard candy of the word”, which must be turned around in the mouth before digesting. God has no limits, but the scriptural pattern appears to be that he speaks when we pay attention.

2. The call to study

Woven throughout the history of the Church is a tradition of deep, reflective study. This helps to inform our understanding of who God is, who we are, and how we’re called to live. It’s not that we need to study, but there’s a goldmine of Spirit-led thought available to help us to grow. Here, we can strengthen our relationship with God, and encourage others with the insights that we’ve gained. Without study, our outreach to the world can suffer.

We perhaps saw the impact of this in 2008. As the new atheism movement grew, many Christians felt unsettled by the so-called intellectual scrutiny that their faith was being subjected to. It’s strange that we should lack intellectual confidence, considering the breadth of scholarship which exists within the Church, and the call of 1 Peter 3:15-16 to “always be ready with an answer” for the hope we have in Christ. Did we miss an opportunity to present this fully, at the time; and are we still missing it now? Perhaps so, if we allow ourselves to become perpetually distracted.

3. The call to a healthy thought life

Aside from the spiritual benefits, focus can be mentally healthy too. The rise in poor mental health has been linked - in part - to an overuse of social media, as we dwell on comparison and negative thoughts. One of the most scientifically well-attested therapeutic models is CBT, which shows how responsible thinking can lie at the heart of sound mental health. Christians know this well, because scripture tells us all about the importance of our thought life. Consider Philippians 4:8 and Romans 12:2, which highlight intentional thinking as a requirement for growth. Or see Matthew 6:28-30, where Jesus calls us away from worldly distractions, to focus our attention on God.

The adage rings true: what we think is what we become.

4. The call to everyone

Ecclesiastes 3:11 shows us that humans long for eternal meaning, and 2 Peter 3:9 tells us that God wants everyone to find it in him. Revelation 3:20 shows Jesus knocking on the door, wanting to come into our homeplace. To know us. To be with us. Romans 1:20 shows us that God accomplishes this by revealing himself through creation.

He’s speaking all the time, but can we hear him?

Make no mistake, it’s our sin - not our iPhone - which separates us from God; but perhaps society’s distractions make it easier to miss his call. God can work with this - he can even speak through a donkey (Numbers 22:28), but that doesn’t mean that our fast-paced modern world is helpful. Like city lights that mask the stars, our noisy world competes for our attention; tempting us to ignore God’s still, small voice.

What can churches do to help?

There are a lot of nuances which arise when we consider how the Church could respond to almost any social development, and this one is no different. I don’t know what the Church should do; but I do have a few thoughts, which may help.

Firstly, we can - as individuals - cultivate our own walk with Christ; prioritising focused prayer and biblical meditation, making time to unplug from anything which gets in the way. Secondly, we can embrace our limits. Jesus didn’t try to get everything done when he walked on earth. He only did what his heavenly father called him to do, and he was fully present while he did so. We could try doing the things in front of us, without spreading our focus beyond them.

Thirdly, the local church can help us to cultivate the discipline of study, by providing theology and apologetics classes, to help us to grow in our understanding of Christian truth. Fourthly, we can present the Gospel in all its depth and beauty. Simplifying the message may be appropriate sometimes, but many people seem tired of the perceived shallowness of a faster world, and the Bible holds truth to build a life on. We ought to share this fully and confidently.

Finally, we can be a Christian voice in the wider conversation about attention span. If the modern world is changing our capacity to focus, we ought to speak about the spiritual and moral dimensions involved. The Bible has something to say about living a well-nourished life, and it’s more relevant than ever.

A church which looks to feed the hungry probably won’t serve donuts and Doritos, though these have their place now and then. Starving people need good food. In a similar way, we can hold to certain principles around focus, even when the modern world gravitates away from them. This is a genuine Gospel opportunity, at a point of need.

Christian thinker Blaise Pascal once said that “All of humanity’s greatest problems, stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone”. I suppose that sin is the real root of our greatest problems, but Pascal’s point is powerful nonetheless, and it’s never more apt than today.