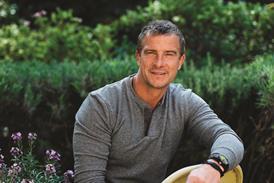

Richard Dawkins and Francis Collins recently sat down with Justin Brierley for a Big Conversation on science and faith…and they got on surprisingly well

It was happening. Richard Dawkins had said yes to my invitation. The well-known Oxford professor and unofficial leader of the New Atheist movement rarely accepts requests to talk with intellectually engaged Christians. This time was different. A long-form conversation on his own area of expertise – biology and belief – with another star of the scientific world, Francis Collins.

Collins is every bit the equal of Dawkins when it comes to biology. A famed geneticist, he led the Human Genome Project, which first sequenced the DNA of the entire human body. He recently retired as head of the National Institutes of Health in the USA, after leading their response to Covid-19 and, at the time of our conversation, had just been appointed acting science advisor to President Biden.

Whereas Dawkins is the world’s pre-eminent atheist, Collins is a committed Christian who founded BioLogos, an organisation dedicated to showing the harmony of science and faith. His bestselling book, The Language of God: A scientist provides evidence for belief (Simon & Schuster), was a counterpoint to Dawkins’ The God Delusion (Bantam Books) and argued for the rationality of Christianity from the perspective of science, reason and experience.

WHETHER OR NOT THERE IS A GOD IS THE BIGGEST QUESTION YOU COULD ASK

Anyone expecting an explosive debate between the two would have been disappointed. Their mutual respect for each other as fellow scientists shone through, with Dawkins quizzing Collins on his expertise in genetics and Collins approaching the conversation as a friendly encounter between two old sparring partners.

Dawkins also warmly thanked Collins for the medical care he had provided their mutual friend Christopher Hitchens during his terminal illness. Collins was able to add several months to the atheist’s life through genomic analysis and treatment of his oesophageal cancer. No wonder Hitchens referred to him as “the best of the faithful”.

Their conversation ran the full gamut of questions of science and faith – whether evolution can be reconciled with Genesis; why God allows suffering; how we developed our moral instincts, and whether a scientist can countenance the idea of miracles. But it was when they reached the biggest questions of cosmic purpose that the most fundamental differences between the two emerged. Collins raised the question of where the universe came from: why do its physical laws seem to be so perfectly set up to produce conscious, living creatures like ourselves? Could there be an explanation in an ultimate designer?

Dawkins has often claimed that science and reason naturally point towards atheism. But, when confronted with the appearance of design in the fundamental architecture of the universe, even he admitted it was “the nearest approach to a good argument [for God]”.

Not that the atheist is about to convert. Dawkins says the concept of God throws “a ruddy great spanner” into the beauty of Darwin’s concept that complex things emerge from simpler ones. He also dislikes the idea of a God who intervenes miraculously. Collins sees a simple beauty in nature too, but says that the God who set up the laws that produced living things also has the power to override them, and did so when he stepped into his own creation 2,000 years ago.

Justin Brierley (JB): Richard, you’re well known as an atheist as much as a scientist. At what point did you come to the settled belief that God and science don’t mix?

Richard Dawkins (RD): About 16, I suppose. My lingering religious faith had been based upon my wonder at the natural world – the beauty, the elegance of the biological world. And so I retained a belief in some kind of creator because I felt that level of complexity needed a designer. And then when I finally understood the full magnitude of the Darwinian explanation, that dropped away and I decided it was actually a counter to what I took evolutionary science to be about.

JB: What prompted you to change from being someone who talked about science to what you’ve been very well known for in the last 15 years or so, with The God Delusion?

RD: Well, it’s a minor part of what I’ve been doing; virtually all my books now are about science and that’s what I would wish to be remembered for. I was not very happy about the election of George W Bush…it was the feeling that there was a kind of religious takeover. My literary agent, who had been discouraging me from writing a book about religion, said: “Now is the time to write it” – and so I did.

JB: Francis, remind us of your story briefly. You became a Christian as an adult, so just explain the circumstances of that.

Francis Collins (FC): When I was 16 or 17 I was also pretty convinced there was no need for God. My comeuppance was going to medical school, because I had this urge to see how science could apply to the human condition in beneficial ways, and I was really excited about DNA in that regard. And then I began to realise there were questions that science wasn’t helping me with, like: “Why am I here?”, “What happens after you die?”, “Why is there something instead of nothing?” And I began to realise I was a bit impoverished in my ability to approach those things. I set about trying to understand how people had answered those questions and I quickly found myself in theological quarters. I thought I would be able to shoot down all their arguments. To my surprise – and particularly influenced by the writings of CS Lewis – I realised that my arguments were actually pretty superficial. Ultimately, over a two- year period, with a lot of kicking and screaming, I came to the conclusion that faith was more rational than atheism.

JB: Richard believes Darwin made it possible to be a fulfilled atheist, because he explained how natural selection could bring about the complex organisms that people assumed must be the work of a creator. What’s your response to that, Francis?

FC: Certainly, evolution is incredibly powerful as an explanatory science to understand the amazing diversity of creatures that we see around us. But I don’t see how it, in any way, excludes the possibility that there was a plan. If God had the intention of ultimately putting, on this small blue planet somewhere on the outer edge of a galaxy, creatures with big brains who would have conversations like this and who might even be interested in whether there is something beyond what they can see, materially – wouldn’t evolution have been a very elegant way to do so?

RD: If I were God and I wanted to create life, I would not use such a wasteful, drawn-out process; I think I’d just go for it. I mean, why would you choose natural selection? Why would God have chosen a mechanism to unfold his design…which actually makes him superfluous? If I wanted to make complex life, I wouldn’t choose that astonishingly wasteful, profligate – cruel, actually – way of doing it; natural selection is cruel.

FC: Those are all really appropriate questions and I wrestle with some of those myself. I don’t think the fact that it took a long time should trouble us particularly from God’s perspective. Yes, it’s a long time for us, but in this view where God is outside of space and time, it’s a blink of an eye. Also, one of the things that I have come to appreciate about this model is it says that God is really interested in order. God is not so excited about the idea of just snapping his fingers; he wanted a universe that was going to follow these elegant, mathematical laws which, by the way, are one of the signposts I see of an intelligence beyond the universe. Einstein would have agreed with that part as well. I get that from our human perspective it’s not necessarily the way we would have done it, but I’m always a little careful of suggesting God should have done this differently because I would have had a better plan.

RD: Yes, it’s a small point really.

I think a bigger point is that it is a betrayal of everything that Darwinism stands for, to smuggle in a creator.

If you really understand that the evolutionary process starts with simplicity and builds up to complexity and elegance and beauty, then to smuggle design in at the beginning is to betray the entire enterprise.

FC: I’m arguing not that the evolutionary process is incapable of generating complexity; I think it totally is. But you believe it’s a result of the laws of physics. I want to take this back a step [and ask] – where did those laws come from?

RD: Most physicists agree that if you change things like the speed of light, gravitational constant and strong and weak force – any of those constants – by even a very small amount, then the universe doesn’t come into existence. They have to be like that in order for galaxies to form, for stars to form, for chemistry to form. And the prerequisite for life to evolve needs that as well. So that’s the nearest approach to a good argument.

By the way, I want to be really careful about this, because I’ve said that before and people have declared: “Dawkins is a convert!” I’m not quite there!

JB: Richard, would you be disappointed, ultimately, if God was the explanation? Would you prefer a Darwinian explanation of the universe itself?

MATHEMATICAL LAWS ARE ONE SIGNPOST OF AN INTELLIGENCE BEYOND THE UNIVERSE

RD: Yeah, that’s a fair summary. On the other hand, I will say that I don’t think this is a trivial question: I think that whether or not there is a God is the biggest question that you could ask.

FC: I would argue that the universe has exactly the properties you would expect if it was put there by God who desired creatures like us to exist; creatures who could be morally responsible, love and care for each other, appreciate beauty, know the difference between good and evil and ultimately seek a relationship with God.

RD: Then what about all the horrible parasites and predators?

FC: You can’t have it both ways. If you’re going to set natural laws in place, including evolution, to ultimately result in something amazing and beautiful – creation – it’s going to also do other things along the way. And God can’t step in every time and avoid parasites – it’s all part of the fact.

RD: But you’re having it both ways when you believe in miracles. You cannot have a God who does miracles on the one hand, and yet who lets the laws of physics play themselves out without interference on the other.

FC: I think I can have it both ways. God is the author of natural laws and when he has a message for the people that he cares about, he chooses to interfere with his own natural laws. Something like this happened with the resurrection. I don’t find that to be intellectually inconsistent.

RD: God is betraying his own principles then…isn’t that inconsistent?

FC: As the author of natural laws, I believe God is entirely able to decide to briefly suspend them. But if he was doing that every time there was a hurricane, think of the chaos around us. How would we ever possibly manage to cope with this world if we had no predictability about how matter and energy is going to behave?

RD: God is betraying his own principles…

FC: No, he is choosing – because he is able to do so – those moments of remarkable importance to convey a message to his creatures, in a way that the miraculous may be able to achieve.

RD: Yes, he would have the power to, but then: “OK, I’m not going to intervene in this earthquake, because that would be inconsistent with the desire to let things play out, but I am going to intervene to heal Jairus’ daughter or raise Lazarus from the dead”?

JB: It’s funny you mention that story, Richard – I was only reading it to my six-year-old son this evening, and it comes at the point where the power has gone out of Jesus as a woman touches his hem on the way to Jairus’ daughter…

RD: I don’t think Francis believes in those events.

FC: I do. I think they are recorded by reliable witnesses who observed these things happening, and I have no reason therefore to question them more than I do to question the resurrection, which is the most critical miracle of all. And without the resurrection, my Christian faith really doesn’t have any substance.

RD: So you don’t intervene with earthquakes, you don’t do any other miracles – then suddenly, during a 30-year period from AD0 to AD30, a whole host of miracles happen? It doesn’t add up.

FC: Well, it was not just any 30-year period, it was the moment where God actually became human. So if there was ever a moment in which the miraculous could be experienced by humanity, that would be it.

WITH A LOT OF KICKING AND SCREAMING, I CAME TO THE CONCLUSION THAT FAITH WAS MORE RATIONAL THAN ATHEISM

RD: But you must see that you’re being unscientific there? You’re suddenly departing from everything you’ve been saying.

FC: You must see that you’re applying your own view, that anything that can’t be explained naturally must be an intellectual error. You and I are different in that regard. I’m allowing the possibility of the supernatural – a creator God who’s responsible for everything.

RD: Yes, I’m kind of amazed actually…I don’t want to get into biblical scholarship, but you must be aware that a huge number of biblical scholars don’t take all the miracle stories seriously?

FC: I am aware, and I will be happy to listen to their arguments if there are specific ways to discount one or the other. When it comes to the resurrection, though, please read Tom Wright’s wonderful book, The Resurrection of the Son of God [SPCK], if you want to see the kind of scholarship that anyone would want for the most significant miracle of all time.

Watch the full conversation between Richard Dawkins and Francis Collins at thebigconversation.show