In this season of Advent, the Church doesn’t just look back to the birth of Jesus in a stable, but forward to Christ’s second coming, says Rt Rev Dr Jill Duff

I love the Far Side cartoons. My favourite depicts Middle-aged Woman opening the door to two smartly dressed men who ask her: “Have you found Jesus?” Off to the right you can just about spot a man in sandals and a white robe hiding behind her curtains.

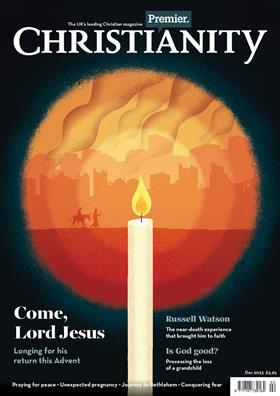

Advent simply means ‘coming’ – the arrival of Jesus. At Christmas, we instinctively focus on his first coming, as a baby in a stable, surrounded by shepherds, angels, a star and some wise men. In contrast, Jesus’ second coming is often the butt of our cheesy Christian jokes. Who hasn’t been in a sluggish church meeting where someone quips: “You never know, Jesus might return first”? His return is quietly consigned to never-never land, somewhere over the rainbow.

But there was a moment last summer when I woke up. I was at an ordination of two priests and, as we sang the hymn ‘I cannot tell why he, whom angels worship’, something shifted in my heart. And it wasn’t just the lilting, Scottish tune of ‘O Danny boy’.

“I cannot tell how all the lands shall worship / When, at His bidding, every storm is stilled / Or who can say how great the jubilation / When all the hearts of men with love are filled / But this I know, the skies will thrill with rapture / And myriad, myriad human voices sing / And earth to heaven, and heaven to earth, will answer / At last the Saviour, Saviour of the world, is King.”

Why, after nearly 2,000 years, has Jesus still not returned?

I found myself holding back gentle tears as I longed, with all of my heart, for Jesus to return soon. Like the closing verses of the book of Revelation, my spirit awoke to that guaranteed promise with no expiry date: “Surely I am coming soon” (Revelation 22:20, ESV). My heart responded with full throttle: “Come soon, Lord Jesus.”

Jesus’ return featured prominently in the lives of early Christians and the Church’s creeds – for example at Nicea (AD 325): “He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end.” But in our 21st- century theology, as we emerge from under the rubble of 200 years of critical scholarship, the second coming has been consigned to the joke book. This is a big oversight.

So I invite you to join me as I blow the dust off the prophecies surrounding Jesus’ return. We will consider the hints given by Jesus, Peter and Paul – those with ringside seats – and delve into some of the end-time themes contained in the book of Revelation.

Today and all days

First, some immediate context. Throughout history, at times of political upheaval, interest in Jesus’ second coming has piqued. On the tail of a global pandemic, current fragility in the Middle East and talk of impending environmental crisis, we are arguably living through a time of unprecedented upheaval.

Or are we?

One uniting point is that every generation believes it is living in the end times. In last month’s issue, Chine McDonald wrote about Chinese students wearing T-shirts with the slogan: “We are the last generation”. Yet in 1948, CS Lewis wrote an essay called On Living in an Atomic Age. In it, he said: “In one way we think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb. ‘How are we to live in an atomic age?’ I am tempted to reply: ‘Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents.’

“In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation…It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

At Christmas, we instinctively focus on his first coming, as a baby in a stable

“This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things – praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts – not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.”

Our natural self-absorption and self-centredness means we assume - like every generation- that we are the ones living through the end times. Jesus was sanguine about our collective instinct to catastrophise: “When you hear of wars and rumours of wars, do not be alarmed. Such things must happen, but the end is still to come” (Mark 13:7).

Sudden and unmistakable

Jesus’ return will be sudden and unmistakable. He won’t be hiding behind the curtains as in a Far Side cartoon. In his own words: “the Son of Man in his day will be like the lightning, which flashes and lights up the sky from one end to the other” (Luke 17:24).

He will return like a thief, at a time we least expect (see 2 Peter 3:10). There will be no advance warning, much to our disappointment. Naturally, we love to be in control, to join the dots of world events as a crescendo to knowing the day on which he will come again. But he does not leave us that option.

Judgement for all

Jesus will return as judge. Understandably, this is not a popular theme for Advent sermons. But it is strongly woven throughout scripture. Jesus will pay special attention to justice for those who have been oppressed, both on a small and large scale. Small scale – how did we respond to our needy brother or sister (see Matthew 25:31-46)? Large scale – he will bring judgement on the “whore of Babylon”, dismantling our alluring macro-economic structures, which have seduced the kings of the earth, and our ways of operating that have become “haunts for demons”, treating “the souls and bodies of men” as mere commodities (see Revelation 18:1-13). We are so woven into this system, weeds and tares together (see Matthew 13:24-30), it is impossible to imagine his harvest time.

A kingdom without end

The only way that wars, famine, plagues, sickness and evil will come to an end is through the return of Jesus, who will usher in a kingdom without end. The violence and atrocities of the 20th century have put paid to the modern myth of human progress. Rather, we have incontrovertible evidence that “The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart”, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said in The Gulag Archipelago (Perennial). We need a divine heart surgeon to bring redemption in every fibre of our existence through the saving work of Jesus on the cross. The whole of creation waits in eager longing for this moment, “groaning in the pains of child birth” (Romans 8:23).

I found myself holding back gentle tears as I longed, with all of my heart, for Jesus to return soon

It is impossible to find words, pictures or analogies to begin to describe God’s new creation, or what is meant, when it says in Revelation 11:15, that: “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he will reign for ever and ever.” After a series of open- heaven visions of the end times, the book of Revelation speaks beautifully of that day when: “There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain” (Revelation 21:4). What is to come is as different from the present as a plant is from a seed, to summarise Paul reaching to describe the indescribable mysteries of heaven in 1 Corinthians 15:35-41: “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known” (1 Corinthians 13:12).

So, in the meantime, how should Christians live? And how should we wait when we have been waiting nearly 2,000 years?

Keep awake

Jesus’ watch word about the future was: “Keep awake”. This theme appears over and over again in his teaching and parables (see Mark 13:33-37, or the parable of the ten virgins in Matthew 25:1-13). We find it in Paul’s letters too (Ephesians 5:14). In fact, the biggest temptation for the saints in this waiting period is not heresy or division, but simply growing weary and giving up (Hebrews 12:3).

In his book, The Church of Tomorrow (SPCK), John McGinley writes of the courage we need to live distinctive lives, awake and obedient to Jesus. He uses this example: “A number of years ago, a Christian couple who were being persecuted in Iran had the opportunity to move to the USA, and they did. After living there for a period of time, the wife began to plead with her husband that they move back to Iran. ‘Why?’ he asked. She told him, ‘It’s like there’s a Satanic lullaby here, and the Christians are falling asleep. And I’m falling asleep! Please, let’s go back’”.

Call his children home

Why, after nearly 2,000 years, has Jesus still not returned? I love how Peter, who had personal experience of God’s patience, explains this: “With the Lord a day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like a day. The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. Instead he is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:8-9).

We can sometimes (mistakenly) think that God is like some headmaster in the sky, sitting in judgement on the morals of our nation. No. This is why we need scripture. God is not like we think he is. When Jesus saw the crowds, his heart was “moved with compassion” because they were like sheep without a shepherd (Matthew 9:35-38, NKJV). In English, the word ‘compassion’ can sound ever so pastoral, even sickly sweet, but in the original Greek, it is visceral, painful, agonising. You might say something more like: “His guts were twisted.”

It’s the same word Jesus uses in the parable of the prodigal son. Here, we have the Father, whose heart has been broken by his younger son leaving home with his share of the inheritance. The old man waits in agony every day, straining for a sign of him on the horizon. Then the day comes when he spots a tramp on the road home. The son has spent all his father’s money on prostitutes and wild living. He comes back armed with self-centred excuses. He’s taken his father for a ride, big time. But his father misses him so much, he just wants him to come back home, no questions asked: “But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms round him and kissed him” (Luke 15:20).

In short, the incredible revelation – as shocking today as it was then – is that Jesus says the agony in the heart of God for us is the same as that of a father who has lost his son. That is why he is waiting to return.

In a meeting a few years ago, I told a story about the fire of love in the heart of God for his missing sons and daughters. In the coffee break, a couple came to speak with me: “You weren’t to know this, but today is the 20th anniversary of our son’s death. It all started when he went missing.” We were all in tears by the end of it. They were happy for me to share this with the gathered company. It seemed a wonderful serendipity of the Spirit to honour them, their bereavement and their beloved lost son.

This is the heart of gospel. From the fire in the heart of God, the Spirit is calling out: “We miss you, please come home.” At the climax of the book of Revelation, after all the glimpses of judgement and the end times, Jesus reassures us: “Yes, I am coming soon” (Revelation 22:20). Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!

He is waiting. And one day he will bring us home. It is a message worth remembering this Christmas, and all year round.

No comments yet