This week the UK celebrated its first Hindu prime minister, but nearly 5,000 miles away in India, where most of the world’s Hindus live, Christians are being attacked and killed for their faith. Sunny Peter explains how a largely peaceful religion has been co-opted by fundamentalist groups

In March last year, two nuns belonging to the Sacred Heart Congregation of the Delhi Province, were accompanying two 19-year-old postulants (nuns in training) on a train journey home for Easter. En route from India’s capital to the eastern state of Odisha, a group of radical Hindu co-passengers (all male) accosted the nuns, accusing them of promoting religious conversion – an allegation that Christian missionaries in India have faced for several decades.

By 7:30pm, when the train reached Jhansi railway station in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, the police were already waiting. But instead of stopping the mob, they forced the four women to alight and took them in for questioning. They were soon joined by a group of 150 slogan-shouting Hindu radicals. The terrified nuns were later released, but only after senior officials had confirmed that the postulants were Christians by birth, and had not converted from Hinduism.

Christian persecution

Two months before this incident, on 12th January at Westminster Hall in London, British parliamentarians were debating the “worrying and disturbing” trends in persecution of India’s religious minorities. Conservative MP Theresa Villiers said she did not accept evidence “of systemic or state-sponsored persecution of religious minorities”, and argued that the British government should be focusing on religious persecution in Pakistan instead. A year later, at a similar debate, Minister of Equalities, Kemi Badenoch, further downplayed concerns, speaking about “the Indian Government’s responsibility to address the concerns of all Indian citizens, regardless of their faith”.

Across the Atlantic, however, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) in its report released in April, recommended that India be designated a “Country of Particular Concern”. Its reason: “Because their governments engage in or tolerate systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations”. Notably, this is the third consecutive year when USCIRF has categorised India in this way.

There is a fictitious narrative that Hindus are being forced to convert to Christianity

The last two years have been of particular concern for India’s Christian minorities. The Evangelical Fellowship of India (EFI), founded in 1951 as the umbrella body of more than 35,000 churches across the country, recorded 505 attacks on Christians in 2021. It says this is the worst violence since the general election campaign of 2014 that brought the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, to power. According to a distress helpline set up by the United Christian Forum, an NGO that supports the human rights of Christians in India, there were as many as 302 attacks on Christians in the first seven months of 2022. The data show Uttar Pradesh has seen over 80 such incidents, followed by the central state of Chhattisgarh, which reported 60 cases. Observers believe the actual numbers could be much higher, as many attacks go unreported due to fear of reprisals.

The victims of these attacks, particularly in semi-urban and rural areas, live in increased fear and insecurity, Fr Cedric Prakash told Premier Christianity: “When these attacks are in remote areas the victims there have no possibility of getting justice”. Fr Cedric, a Jesuit priest, writer and human rights activist, is well known for his work among the poor, marginalised and minorities of India. He believes the strawman of ‘forced conversions’ raised by radical Hindu nationalists has little basis in fact, and has a “detrimental impact on the good work done by the Christians”. He says Christian missionaries are increasingly “looked upon with suspicion” by the majority Hindu community as a result of these accusations.

A short history of Christianity in India

Christianity has found a home in India for close to two millennia. It arrived when the Apostle Thomas landed on its shores in the southern state of Kerala in AD 52. Christians missionaries, both Western and Indian, have since been an integral part of the nation, contributing towards its social, cultural, political and economic progress. Many serve among the very poorest in India.

Western missionaries like British Baptist William Carey, a linguist and educationist, mastered Sanskrit, Bengali and other Indian languages and even translated Mahabharata and Ramayana, two of India’s greatest epics that form the core of Hindu thought and belief. There were others, such as C. F. Andrews, an Anglican missionary, educator and social reformer, and R. R. Keithahn, an American missionary and social worker who worked closely with Indian nationalists and was involved in the country’s freedom movement.

Meanwhile, thousands of others, like Nobel Laureate Mother Teresa, the Indian saint from Albania who founded the globally renowned order of the Missionaries of Charity, dedicated their lives to care for the destitute and dying.

Although India’s constitution is secular and its Article 25 offers citizens the fundamental freedom to profess, practice and propagate their religion and belief, the Hindu nationalist elements governed by the BJP have prodded state after state to pass anti-conversion laws, paradoxically called “Freedom of Religion Acts”, which regulate religious conversions. This so-called anti-conversion legislation has repeatedly been used to harass and attack Christian and Muslim minorities, although few prosecutions have been made under its provisions.

Contrary to the raucous allegations of large-scale forced conversions by Christian missionaries, the percentage of Indians who follow Jesus reveals a different picture. India has a Christian population of 2.3 per cent in a country where Hindus make up roughly 80 per cent. Among the people of other minority faiths, Muslims comprise 14 per cent, Sikhs 1.7 per cent, Buddhists 0.7 per cent and Jains 0.3 per cent.

The Christian population in India has, in fact, been on a slight but steady decline over the decades. According to the national census in 1971, Christians in India made up 2.6 per cent of the population, which in 1981 declined to 2.4 per cent. It then dipped to 2.3 per cent in 2011, which offers the last available census figures.

Despite the statistics, a fictitious narrative has been spread that there is a rise in the number of Hindus who are either forced to convert to, or lured into, Christianity — and that anti-conversion laws and the eventual creation of a Hindu nation is the only way to push back against Christian missionary activities.

A Hindu nation

Hinduism is one of the world’s oldest religions, tracing its origins back to about 1500 BC during the ancient Vedic civilizations. Although 94 per cent of the world’s Hindus live in India, the country is also home to the world’s third-largest Muslim population, and substantial numbers of Christians and other minority faiths. Christianity found a home in India close to two millennia ago, when the Apostle Thomas landed on its shores in the southern state of Kerala in AD 52.

Since independence, elected governments have taken particular care to emphasise the country’s religious diversity. However, within the pluralistic traditions of Hinduism, is the radical Hindu nationalist ideology – or Hindutva – that advocates Hindu supremacy and seeks to create an exclusive Hindu nation in India.

The design of a Hindu nation begins with the right-wing definition of who is a Hindu, and what is “Hindutva”, the term used by Hindu nationalists to represent their resurgent fundamentalist political ideology. In his 1923 pamphlet, Essentials of Hindutva, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a right-wing hero who popularised the term Hindutva, redefined what it meant to be Hindu as: “A person who regards this land of Bharatvarsha [India], from the Indus to the Seas as his Father-Land as well as his Holy-Land that is the cradle land of his religion.”

Contrary to the inclusive and pluralistic nature of Hinduism, Savarkar attempted to reduce national identity to a purist ideological concept that usurped the other distinct Indian minority faiths of Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism. He craftily repudiated Christianity and Islam, by inferring that they were foreign faiths because their “Holy-Land” lay beyond its geographical shores – in Israel and Arabia.

Christian missionary Graham Staines and his two young sons were burned alive in their jeep while they were sleeping

Inspired by the idea of Hindutva, the task of championing the cause of building a Hindu Rashtra (nation) was taken up by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a right-wing Hindu nationalist and paramilitary volunteer organisation founded in 1925. Within the RSS super-structure are a collection of several outfits, each serving a specific objective: to build a Hindu Rashtra.

The BJP, the party that now holds power in India’s government and in several states of the country, is the political outfit of the RSS. Apart from the BJP, there are numerous other affiliate organisations, including the religious organisation called the Vishva Hindu Parishad (World Council of Hindus) along with its militant offspring, the youth wing Bajrang Dal. Together, these organisations spawned by the RSS are known by the umbrella term Sangh Parivar (RSS Family). The RSS today also has a presence across the world, particularly in Europe and America.

The BJP has used ethno-religious anxieties relating to Hindu national identity, mixed with hate for minorities, as a tool to capture political power. In the process they have subverted the very ideals and values with which the Indian Constitution was founded.

Over the decades, the Sangh Parivar outfits have nurtured a false narrative of an impending religious takeover by Muslim or Christian minorities, fanning a fallacious sense of insecurity and anti-minority sentiment among the majority Hindu community. This has been channelled towards violent attacks on minorities and their institutions.

Ten days of terror

One of the worst premeditated attacks so far happened over ten days in the forested Dangs district in the western state of Gujarat during Christmas 1998 – the same year that the BJP took control of the state. Thousands of Hindu radicals armed with iron rods and other weapons, attacked, looted and set fire to churches, prayer halls and the houses of local Christians.

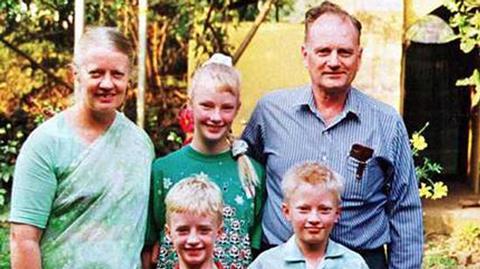

A month later, the state of Odisha witnessed the most gruesome killing of 58-year-old Australian Christian missionary Graham Staines and his two young sons, Philip and Timothy, aged ten and eight, burned alive in their jeep while they were sleeping. Staines had been in Odisha since 1965 as part of an evangelical missionary organisation working among leprosy patients and the poor. Radical Hindus had alleged that Staines was involved in the forcible conversion of tribal people to Christianity.

Less than a decade later, in 2007 and 2008, and reminiscent of the violence witnessed in Dangs, another forest district was targeted. Houses, prayer halls, churches and Christian institutions in Kandhamal, Odisha, were burned and Christian families forced to flee for their lives. The attack saw close to 400 churches destroyed, around 6,500 houses damaged and schools and hospitals looted. Over 75,000 people were displaced. Several cases of forced conversions to Hinduism were reported, and about 40 women were raped and over 100 people murdered.

The kind of violence witnessed in Dangs and Odisha aimed to “denigrate, demonise and discriminate against Christians and other minorities”, says Fr Cedric. They were accompanied by an “official denial” by certain groups. Today, attacks by vigilante groups are “blatant, direct [and involve] the ‘officialdom’ giving legitimacy to and protection to the perpetrators”. Police cases are not filed, and if they are, they are manipulated, he says: “More often than not, the victims are made the perpetrators of the crime”. If the leadership of the BJP or the Sangh Parivar were to condemn these attacks “everything would have stopped”, he adds.

There is no easy way to differentiate between state-sponsored attacks and state-supported attacks on Christians

Emerging as a hot-bed of anti-Christian sentiment is Chhattisgarh, where in October 2021 at a rally against the alleged forced conversion of Hindus into Christianity, a far-right Hindu leader speaking in the presence of BJP leaders urged the people to “arm themselves with axes to teach Christians indulging in conversion a lesson”. He encouraged them to follow a “Roko, toko, thoko” dictum – Stop, warn and kill.

“Whether it is in the Dangs or in Kandhamal, genuine Christians who embrace Jesus and the Cross, have always deepened their faith and come out stronger [from persecution]. There is no doubt about that,” says Fr Cedric, who is choosing to focus on hope, not hate. But in the meantime, certain quarters aim to make the lives of Christians very difficult.

Like hundreds of other Christian institutions and NGOs, the Missionaries of Charity (MC), founded by Mother Teresa, has come under repeated virulent attacks of another kind. They have faced unsubstantiated allegations from the media and needless harassment by government agencies. In December 2021, the police in Gujarat filed a case against one of their orphanages alleging that girls in the institution were being forced to read the bible and participate in Christian prayers with the intention of “steering them” towards Christianity. Even though the management of the MC denied the allegation, the police initiated an investigation, only to drop the charges later, having found no evidence. Around the same period, reports said the Indian government had decided to suspend FCRA approval of the group (a legal requirement for receiving foreign donations in India) leading to an outcry from opposition parties and human rights groups. FCRA approval was later restored. However, as Archbishop Joseph D’Souza writing in Premier Christianity points out, there are thousands of other non-profits who remain in limbo due to the government’s decisions on FCRA approvals.

Saving a democracy

Since Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014, the Hindutva nationalist ecosystem has become widespread, with its tentacles spreading out widely across the country, and even abroad.

Early last month, the Indian government told the country’s Supreme Court that a public interest litigation filed by Christian groups urging action against attacks was based on “self-serving reports”. As the government side-steps the concerns raised by minorities, rabid Hindu elements continue to carry out attacks on trumped-up, fabricated charges of conversion, while giving clarion calls to take up arms for the creation of a Hindu Rashtra with a new constitution.

There is no systemic or state-sponsored persecution of religious minorities, the nature of which we see in China. However, when one arm of the Hindu nationalist ecosystem is in power with a brute majority (the BJP), and attacks on minorities are carried out by its other tentacles, there is no easy way to differentiate between state-sponsored attacks and state-supported attacks.

Despite predictions by naysayers, and unlike many of its neighbours, India has flourished as a democracy. Its survival as a democracy is, however, closely aligned with its ability to sustain its identity as a secular nation. India’s founding leaders and the constitution framers knew this when they created a democratic republic. But considering the phenomenal rise of Hindu nationalism in its political landscape, the question is: will India remain a democracy? And will Christianity, which has been present in this country for millenia, be tolerated?

No comments yet