More people of all faiths and none are choosing to pull on their boots and take to the ancient paths of pilgrimage. Emma Fowle heads to Spain to find out what it’s all about

When I arrived in the port city of Santander to walk part of the Camino Lebaniego, I did not really know what to expect. As someone who loves the outdoors, travelling and new experiences, I was excited to visit a part of Spain I had never been to before, to walk in the beautiful Picos de Europa mountains, eat good food and meet new people.

But like many who strap on their hiking boots and take to The Way these days, I had little knowledge of the religious concept of pilgrimage, or the Catholic traditions that underpin it. Nonetheless, I was keen to embrace the spiritual discipline of slowing down, enjoying God’s creation and taking some time out of my otherwise always-on life.

The path of pilgrimage

Christians have been making special journeys to significant holy sites since the fourth century. The most famous of these, the Camino de Santiago, or Way of St James, is a network of routes that converge in Santiago de Compostela where, according to tradition, the remains of the apostle James - credited with bringing Christianity to Spain - are buried.

Last year, just under half a million pilgrims undertook this famous journey. But while many follow one of several set paths to Santiago, there is no one ‘way’. A pilgrimage starts wherever you are, my guides explain. It is, they say, simply a journey; less about the route and more a posture or a spiritual practice.

Pilgrimage is a way of life. Along with three other journalists of various ages, nationalities and faith backgrounds, we were heading for the Lebaniego Way, a 71-kilometre route that runs inland from the coast to the monastery of Santo Toribio de Liébana. Although less famous than the Way of St James, it is nonetheless of great spiritual importance. At its end lies The Wood of the Cross, or Lignum crucis, believed by some to be the largest known surviving piece of the cross of Christ.

According to tradition, this was brought from Jerusalem by St Toribio of Astorga and taken to the monastery in Liébana for safekeeping during the Muslim invasion of Spain in the sixth century. Its presence makes Liébana an important pilgrimage site, one of five places in Roman Catholicism where indulgences can be gained. This complicated – and sometimes contested – concept is understood within Catholicism as a way to remit the punishment or consequences of sin, often through prayers, acts of charity or other spiritual practices. The idea is rooted in an understanding that, while the eternal punishment of sins are forgiven by Christ’s death on the cross, there are temporal (earthly) consequences that endure.

Penance can play its part in addressing these consequences, as can the indulgences gained by pilgrimage. In certain ‘jubilee’ years, pilgrims flock to pass under the church’s Holy Doors, an even more significant experience than gaining the usual, temporal indulgence.

As a Protestant and evangelical, I’m not sure what I think of this talk of relics and indulgences, or many of the stories and traditions that I encountered during my trip. Nevertheless, I was keen to try and understand more and find God where I could.

Finding God

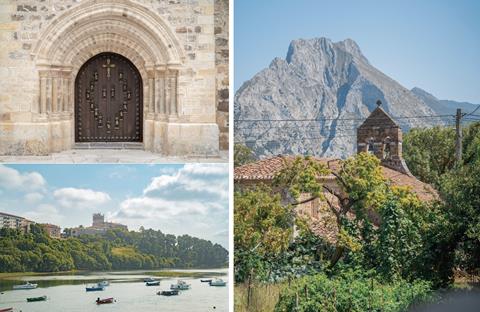

Our first day started at Iglesia Santa María de los Ángeles; ground zero of the Camino Lebaniego. The church itself is an imposing building that stands high on the hillside above the coastal town of San Vicente de la Barquera. Inside, we picked our way across wide, oak plank floorboards that our guide told us were made from old coffins. She explained the history of the beautiful baroque altarpieces and regaled us with stories of the church’s namesake, Santa María, a statue of whom miraculously appeared one day, floating on a fishing boat in the estuary.

Afterwards, we gathered around the waymarker on the ground and grinned, the sun breaking through the September clouds. We wandered around the town, ate lobster and rice (the seafood in northern Spain is exquisite) and then, finally, we took to the trail. As we walked along the Nansa River, we heard about the rewilding project that the Foundation of the Camino Lebaniego have instigated, designating it a green corridor and using the opportunity afforded by tourism to benefit the rural community. We learned about the area’s traditional industries and how the trail is bringing more visitors to this beautiful part of Spain. When we finally made it to our pilgrim’s hostel that evening, we were tired - and a little wet and cold from an unexpected afternoon downpour that soaked us to the skin - but one more surprise awaited us.

Our guides had organised for the chapel at Los Pumares - one of only four in the region to date back to Roman times - to be opened especially for us. Before we even entered the tiny, limestone church, we could hear the music. As we stepped inside, we let out a collective gasp; candles lit the simple, domed ceiling. A wooden cross hung over the altar as Martha, our hostel owner, played her cello in the twilight. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

A pilgrimage is less about the route and more about a spiritual practice

The contrast between the grandeur of the ornate church where we had started our journey that morning and the rustic simplicity of this one could not have been greater.

As someone who grew up in a church that met in a village hall, I must admit that I have not always appreciated the draw of ornate, gothic churches swathed in gold and filled with (some might say) gory images of weeping saints and blood-stained Jesuses. “Jesus has risen – why depict him still in agony on the cross?” some ask. “How much money did it cost to build this thing?”; ‘Why is it so dark and gloomy?”

I have been on a journey with this in recent years. It might just be getting older, but I am learning to appreciate anew the reverence of beautiful spaces and the mystical faith of those who can believe that a statue of Mary magically appeared in a fishing boat.

There are still many points of theology that differ to my own, but after my first day on the Camino, I’m certain of this: that God can be found in the ornate and the forest floor and along the side of a river. He can be found in the music of a cello by candlelight in a tiny stone church, and in following the footsteps of those who have gone before us for hundreds of years. And he can be found around a table, eating a simple pilgrim’s supper of bread and cheese and anchovies with people who were, just yesterday, strangers - but who were now becoming friends.

Invisible made visible

The second day started at the Santa Catalina viewpoint. The weather forecast and time limitations meant that, instead of walking to the top as planned, we were driven up – which, I must admit, did feel a little bit like cheating. But still, when we gazed out across the Picos de Europa mountains and saw three, huge eagles soaring below us on the thermals and a rainbow creeping across the valley, it really brought to life Paul’s words in Romans 1:20: “For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen.”

EM Forster said that it was the function of art to make us “feel small in a good way” but, for me at least, it’s mountain peaks, sunrises and vast ocean vistas that remind me of my own insignificance - and God’s magnificence. For many people today, a pilgrimage is less about honouring a long-dead saint or visiting a holy relic, and more about reconnecting with God through the beauty of his creation. It’s a way of slowing down, taking a pause and putting things back in their proper perspective. God first. Make time for that relationship. And all else after.

As we navigated the rocky terrain and climbed, our hearts pumping and legs aching, we discussed Romans 5 and how “suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope” (v3-4). More than anything I’ve experienced, pilgrimage embodies those verses. Like any physical challenge, the camino is strenuous, requiring commitment and endurance. But completing such a challenge changes us somehow, too; the sense of achievement we feel from persevering through the tiredness and pain builds our character. Our hope grows that, whatever we face – a stressful situation at work, health scare or heartbreak – with God, all things are possible.

The family of Christ

Finally, we arrived at our final destination, the monastery in Liébana. Going into this trip, I did not have any particular expectations of visiting this place or seeing the relic of the cross, but two surprising incidents affected me deeply.

Firstly, as we were waiting in the gift shop to meet the Franciscan friar who would show us around, a young South Korean couple came in. They smiled shyly and our guide made small talk. Then, as the friar arrived, they became quite animated, trying to explain in broken English that they were Young Franciscans who had travelled from half the world away, on their wedding anniversary, to find the friar who had married them while working in their country as a missionary. They had not received a response to their email, and so had decided to come to Spain anyway, hoping and praying to find him.

As our guide interpreted into Spanish for the friar, he, too, became excited. Miraculously, he knew the man they were looking for and had studied at seminary with him. He had been quite ill, he explained, and had been moved to a different monastery to recover, which was probably why he hadn’t replied to the couple’s email. Then he disappeared, reappearing moments later, speaking rapidly into his mobile phone. Handing it to the young couple, a joyous reunion took place and, as they spoke to the friar who married them four years earlier, the young girl crying with joy, we all shed a tear to see their happiness.

When I touched the small, square inch of exposed wood, I did not expect it to feel so visceral

So why tell this story - one that isn’t about churches or relics or supernatural experiences? Well, as the guide and I were wiping away the tears and laughing at our soft-heartedness afterwards, it reminded me of a very important truth that is often overlooked and easy to forget.

As Christians, we are children of God. Wherever we are in the world, whatever our age, denomination, nationality, class or theology, we have a family of brothers and sisters in Christ who love and care for each other. This is, for me, one of the most beautiful things about the body of Christ. As Paul says in Romans, we are instructed to “rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn” (12:15).

An activity like the camino - much like any intense experience - brings you together like nothing else. As you walk for hours along mountain paths, eat together around communal tables and bunk down at night in dormitories, the usual boundaries are broken down. As you help one another along slippery, rain-soaked paths, bear with each another’s varying walking speeds, cheer one another on and, invariably, get to witness moments of great joy - and, often, sadness, too - you become family, just as God intended it. It ‘s rare in today’s individualistic society, so when we do see and experience it, it reminds us to value it – and seek it out – more often.

The power of the cross

Finally, it was time to see the relic. This 63cm x 39cm piece of wood has been scientifically proven to be Mediterranean Cypress wood, which is very common in Israel, and could be more than 2,000 years old. So, while no one can prove that it actually was part of the cross to which Jesus was nailed, it definitely could have been.

Today, it is encased in an ornate silver cross, a small window at one end exposing just a portion of the wood for pilgrims to touch or kiss. With great ceremony, the priest took it out of it’s gilded wooden housing and laid it on a velvet-covered shelf, beckoning us to approach it. Despite the language barrier and my lack of understanding of this church world, I could feel a ripple of anticipation pass through the room.

We can touch it? everyone’s eyes seemed to be asking. Yes, motioned our guide, nudging us forward. We formed a queue and, as I waited in line, I suddenly felt completely, surprisingly overwhelmed. As a charismatic evangelical, I am not unused to sensing the physical presence of the Holy Spirit; I have cried and been slain in the Spirit, laughed and felt immobilised by the weightiness of God’s presence but being honest, I was not expecting it here.

As I approached the cross, I fought back tears. In fact, that feels like an understatement when describing the onslaught of emotion that I felt. I had to battle to stay upright; to not sink to my knees and lose myself in a sea of tears. It took me wholly by surprise.

I touched the small, square inch of exposed wood, worn smooth by the untold number who had been before me. I did not expect it to feel so visceral. If you had asked me ten minutes earlier whether this relic really was the cross of Christ, I would have politely replied that I thought it highly improbable.

And afterwards?

I had no more proof that it really was. So why did I respond so strongly? I think, for me, it was something to do with the physicality of the experience. So often in church, we sing about Christ’s death on the cross and read about it in the scriptures, but it can become so familiar that it loses its brutality; it’s raw power and overwhelming impact. Being there in that place, feeling the indents left in centuries-old wood by a thousand pilgrim’s hands, it hit me afresh.

Jesus hung on a cross for me.

He was nailed to a real piece of wood for my sins; for all of the selfish things that I have done or will ever do.

Throughout the ages, that has been the point of pilgrimage. Catholic pilgrims have headed for these holy sites to repent of their sins. Whatever your churchmanship, your beliefs about forgiveness or how it is obtained, it’s never a bad thing to remember afresh - and to be eternally grateful for - the mercy that we receive at the foot of the cross.

For more information about the pilgrimage visit caminolebaniego.com

No comments yet