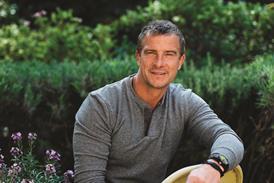

Martin Saunders considers the spiritual messages contained in Wicked: Part One

Are people born wicked, or do they have wickedness thrust upon them? No – this isn’t an article about the doctrine of original sin, although we’ll certainly touch on it; this is the first significant line in the cinematic adaption of Broadway musical Wicked, which swept the world like a witch’s broom at the very end of 2024. It encapsulates the key question addressed by both movie and musical: whether evil comes from inside or outside a person. It’s a concept that Christians today – and throughout history – have had a fair bit to say on.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First, it’s time to reverse down that famous Yellow Brick Road which is, of course, what Wicked is all about. The musical, which first appeared in San Francisco before a now-21-year run in New York, is the pre-eminent instalment in a long-running saga. It revisits the beloved characters and settings first introduced in The Wizard of Oz. But whereas the Judy Garland classic – and the novel that inspired it – focused on a coming-of-age journey and the assembly of human characters, here we’re more concerned with Oz’s famous witches, notably Glinda, the ‘Good’ Witch of the South, and Elphaba – infamously labelled as the ‘Wicked’ Witch of the West.

Are we a people of gravity-defying love, or do we write off those who don’t fit the template?

But are those labels fair or accurate? How did they get them in the first place? That’s what the musical, and now this two-part movie, attempts to explore.

A quick and reassuring caveat before we get into Wicked: Part one: there’s no cause for concern that this marks some sort of worrying cultural descent into witchcraft (although if you want some of that, just head back to the November instalment of this column). It would be a shame to rush to moral outrage because Hollywood is glamorising the witch; if we do that, we risk missing out on a fascinating cultural conversation.

I’m not that girl

Wicked: Part one opens with the famous on-screen death of one of its main characters, before quickly skipping back to her origin story. It’s here that we first meet Elphaba (played by British Catholic actress Cynthia Erivo) and get some snapshot insights into the tragic upbringing that shaped her. Yet while that shape appears to be monstrous (she has bright green skin for magical reasons involving a weird potion and maternal adultery), it belies a gentle, kind character whose only vice seems to be bouts of powerful, righteous anger. On her first day at a university apparently attended almost entirely by 30-somethings, she meets the glamorous Galinda (Ariana Grande), externally perfect but, internally, somewhat vacuous. Through a plot contrivance they become college roommates, and embark on an initially frosty relationship that, over time and through the magic of song, sees them become firm friends – a central relationship that defines the whole film.

Both women help the other with a core problem, blurring the lines between who exactly is meant to be ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Galinda’s social clout helps integrate the formerly ostracised Elphaba into the heart of the college community and enables a romantic relationship for her wheelchair-bound sister. Meanwhile, Elphaba opens a locked door into the world of magic for her roommate, gaining her personal tuition from Michelle Yeoh’s stern sorcery teacher. The friendship strengthens, and the two embark on a journey to the Emerald City to meet its incumbent Wizard, played in scenery-chewing style by cult hero Jeff Goldblum. Yet what appears to be a trip to reward and celebrate Elphaba’s magical prowess quickly turns more sinister, and we realise that while there are wicked forces at work, they are coming from an unexpected direction…

Wicked is a phenomenon, and it’s easy to see why. The songs are catchy, moving and, at times, huge; the plot is both intellectually rich and emotionally powerful. The film adaptation of the musical’s first act certainly lives up to expectation. Both Erivo and Grande give stellar performances, and the supporting cast are excellent. The visuals are stunning, and the staging imaginative – so it’s no surprise that reviews have been largely glowing. But there’s much more to Wicked than the sets and songs.

No one mourns the wicked

The film addresses a few interesting themes, but none are more significant – or relevant for people of faith – than the central exploration of wickedness and where it comes from. Author Gregory Maguire, who wrote the book on which it’s based, chose to focus on the witches of Oz specifically because he wanted to explore this question through introducing moral ambiguity to characters traditionally seen in a strict binary. An American who lived in London during the 1990s, he witnessed the long-running media circus around the murder of Liverpool toddler Jamie Bulger, after which his young killers were widely labelled as ‘evil’. The incident and its response troubled him deeply, leading to what he later termed “the great revelation of my life”. As he told The Guardian in 2021: “Everyone was asking: how could those boys be so villainous? Were they born evil or were there circumstances that pushed them towards behaving like that? It propelled me back to the question of evil that bedevils anybody raised Catholic.” The intersection between his religious upbringing and the vilification he witnessed became the crucible in which Wicked was formed.

Prejudice and fear, both of the outsider and of becoming one, are powerful drivers

The characters of Galinda/Glinda (she drops the first ‘a’ in a hilarious moment of virtue-signalling) and Elphaba are deliberately complex. Both women have noble traits and obvious flaws; both try to be good and feel the pull to do bad. Each is a product of upbringing, circumstance and personal decision, and the resulting point is clearly made: people are much more complicated than we want them to be.

And yet that doesn’t stop us from applying such labels and categories. Prejudice and fear - both of the outsider and of becoming one are powerful drivers. The opening song lays these tensions bare: as villagers celebrate the death of the Wicked Witch, Glinda transmits a profound sense of discomfort. We want to write people off but, deep down, we know it’s not right to do so. It’s a message that the Church might want to both amplify and reflect upon – the gospel of Jesus is all about redemption for those who might feel written off yet, so often, we can be guilty of pronouncing or reflecting that very same sense of judgement.

Something bad

The other relevant theme for Christians involves the nature of anger. At first, Elphaba is ostracised because her occasional fits of rage lead to dangerous explosions of magic. Yet, as we learn more about her, we realise that this is always motivated by her keen sense of justice, and by observing things in the world that are not as they could be. Like Jesus in the temple courts in Matthew 21, Elphaba’s anger is entirely righteous – a virtue perceived as a flaw.

As the film reaches its conclusion – the midpoint in the Wicked story – this goes a step further, and Elphaba assumes another Christ-like position: that of speaking truth to power. Motivated by a desire to overcome injustice, she challenges the powerful to turn from their own evil. What happens in response is somewhat resonant with the world we know: those in power fight to hold on to it, both claiming a supernatural book as their own, and identifying a common enemy that will unite the people behind them. If it’s intended as a commentary on American politics, it’s not a bad one.

To be more provocative: does this also challenge the Church? How ready are we to listen to those uncomfortable outsiders who seek to bring challenge, especially to the established, privileged order? Do we hide behind the power of our ancient text, or hardline dogma that is impossible to fight? In embracing the message of Wicked, we can’t just draw parallels with Jesus’ own heart for inclusion, justice and redemption; we must also face up to the hard challenge that we can sometimes behave like the powerful wizard in his emerald tower.

What is this feeling?

Turning a beloved musical into a successful movie always contains an element of risk (just ask the makers of 2019’s Cats). The consensus appears to be that Wicked – or at least the first half of it – has made the transition unscathed, or even improved. It’s an adaptation with a heart, but it also has a brain, and the courage to ask some difficult questions of its audience.

For Christians it’s both an endorsement of our redemptive message and a cautionary tale about how religious institutions can perpetrate the opposite. Do we seek to understand our spiritual book like Elphaba, or weaponise it like the Wizard? Do we place our leaders on too high a pedestal, and endow them with too much power? And are we really a people of acceptance, inclusion and gravity-defying love, or do we write off those who don’t fit the template? These are all questions for us to grapple with long after Cynthia Erivo’s lung-bursting final note has faded. Just don’t worry about the witches.

Christian metaphor in the Wizard of Oz universe (allegedly)

Given author L Frank Baum’s strong Christian faith, and his assertion that the book may have been divinely inspired, it’s unsurprising that several commentators over the last 125 years have sought to find Christian allegory within the Oz stories. Here are just a few of the creative Christian conspiracy theories

The Wicked Witch is baptised

When Dorothy throws that famous bucket of water over Elphaba, this may actually represent the waters of baptism that melt away wickedness and sin. Especially because the name Dorothy actually means ‘gift from God’.

The Yellow Brick Road is the path of discipleship

Character is formed along the way, until we finally come face-to-face with the powerful God-figure at the end. This is the ‘narrow path’ described by Jesus in Matthew 7; he just forgot to mention the Munchkins.

The Emerald City is heaven

It certainly sounds a bit like the new heaven and new earth described in Revelation 21 – and it does feature an enthroned king.

The story is a re-imagining of The Pilgrim’s Progress

John Bunyan’s classic tale was written in 1678, but includes many of the same plot points as Baum’s tale – minus a cowardly lion, which surely would have only improved it.

The Lion, Tin Man and Scarecrow illustrate Christian character

We witness courage, love and wisdom grow in Dorothy’s travelling companions, the development of which takes place in community, through divine intervention - just like the fruit of the Holy Spirit.

The (Yellow Brick) Road to Oz

Wicked: Part one represents the latest in a long odyssey of stories set around the fictional land of Oz. Here, in reverse, is the timeline.

The Wicked movies (2024/25)

Filmed at a huge, purpose-built set in Buckinghamshire, director Jon M Chu said that the decision to film in two parts was defined by the need to have a curtain-drop moment after central song, ‘Defying gravity’. By happy coincidence, this also meant the film could make double the money. But it’s all based on…

Wicked the musical (2003)

A stage show that has taken the world by storm over two decades and become a permanent fixture in London’s West End and around the world. The original cast featured the dazzling double act of Kristin Chenoweth and Idina Menzel, both Broadway royalty. Writer Stephen Schwartz based his music and lyrics on a book he read on holiday…

Wicked the novel (1995)

By Gregory Maguire, an initially unsuccessful book written by a little-known children’s fantasy author. His own complex childhood may have informed the central character of Elphaba, while his Catholic upbringing brought the question of original sin into focus. Having been fascinated by the idea of writing a book exploring the nature of evil, he chose to do so by revisiting a film he’d always found fascinating…

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Widely regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time (although now marred by a number of controversies), it’s a story that needs no explanation. It was Margaret Hamilton’s performance as the Wicked Witch of the West that inspired Gregory Maguire to write Wicked. But of course, it was all based on…

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900)

By L Frank Baum, the novel that started it all was a huge commercial success, selling more than three million copies. Baum was a committed Christian, who once said the book might have been directly inspired by “the Great Author”, and a man who held problematic beliefs about Native Americans, for which his family have since apologised. The US Library of Congress have called the book: “America’s greatest and best-loved homegrown fairytale”.

No comments yet