On average, minority ethnic staff earn less than their white colleagues in the UK. If we are to tackle racial injustice, companies must be transparent about their ethnicity pay gap, says Sarah Edwards

The cost of living crisis is hitting all of us hard, but its effects are being felt most intensely by the minority ethnic groups that are disproportionately represented in low-income homes in the UK. A 2020 study of racial inequalities found that Black African or Bangladeshi households had approximately 10p for every £1 of white British wealth. Insulating against poverty – and the stress and obstacles that come with it – has always been much harder for these groups, and it has been exacerbated by the challenges of recent years.

One underreported reality is the ethnicity pay gap. Similar to its more familiar sister, the gender pay gap, this metric of inequality tells us something about the value that is placed on the work of different groups in our society.

WHAT IS THE ETHNICITY PAY GAP?

The ethnicity pay gap is the difference in average pay between all Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff in a workforce compared to their white colleagues, irrespective of role and seniority. For example, where there is a gap of 15 per cent at an organisation, it means the pay of staff from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups is, on average, 15 per cent lower than their fellow white workers. This is different from unequal pay – a gap between those with the same roles and responsibilities at an organisation – which is illegal. But even if an employer has a fair pay and reward policy, as well as equal pay, it could still have an ethnicity pay gap. This is because white employees are often disproportionately represented in senior management roles.

Discrimination likely plays a part in this. According to researchers at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Social Investigation (CSI), people from minority ethnic backgrounds have to send, on average, 60 per cent more job applications to get a positive response from employers compared to their white British counterparts. When researchers sent out more than 3,000 fictitious job applications, with the candidates’ ethnic background as the only variable, the results revealed that while 24 per cent of white British ‘applicants’ received a call back from employers, only 15 per cent of the minority ethnic ones did. People of Pakistani origin had to make 70 per cent more applications before they received a positive response and the figure was even higher for people of Nigerian, Middle Eastern and North African descent.

Transatlantic slavery created negative legacies for the millions of people who were exploited, and their descendants

People from diverse backgrounds are not only less likely to be recruited in the first place, but some research suggests they are more likely to become stuck in junior positions once inside an organisation. An internal review into inclusion at the Bank of England, for example, found that staff from minority ethnic backgrounds were less likely to be promoted, earned less and were more likely to feel they were being treated unfairly compared to their white colleagues.

It’s difficult to know the scale of the problem, but the Office for National Statistics’ pay gap data for 2019 shows that, on average, people from minority ethnic groups earn less than people from White British backgrounds (although some, such as people from Indian and Chinese backgrounds, earn more). Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups in particular were negatively impacted, earning on average 16 per cent and 15 per cent less than white British workers, while Black Africans earned eight per cent less.

There are differences within ethnic groups, as well as between genders, ages and regions, which add up to a complicated national picture. But the overall gap is caused by many of the same factors, whether in a FTSE 100 company (the highest value 100 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange), a public sector employer or a small business.

So what’s the solution?

According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, employer reporting is a critical step in “identifying and tackling racial inequality in the workplace”. Gender pay gap reporting has been mandatory since 2017, but despite the government producing guidance in April, the monitoring of pay disparity between workers of different ethnicities is not yet obligatory.

Currently, only a tiny fraction of FTSE 100 companies report on ethnicity pay gaps. It’s certainly more complex than gender pay gap reporting, for a whole host of reasons, but large organisations have the resources to make it a priority. Without the data, we simply cannot provide long-term solutions beyond initiatives to root out unconscious bias in recruitment processes (which is a good place to start, nonetheless). If reporting remains voluntary, many employers simply won’t put the information into the public domain. Where data is collected, it will have limited scope, focusing on representation in the board room and at senior management level, rather than at all levels of an organisation.

The evidence

Black and minority ethnic people generally have much lower levels of savings or assets than white British people.

For every £1 of white British wealth:

Indian households have 90-95p

Pakistani households have 50p

Black Caribbean households have 20p

Black African households have 10p

Bangladeshi households have 10p

All Black and minority ethnic groups are more likely to be living in poverty. This is due to lower wages, higher unemployment rates, higher rates of part-time working, higher housing costs in England’s large cities (especially London) and slightly larger household size.

Percentage of workers paid below minimum wage:

Bangladeshi: 18%

Pakistani: 11%

Chinese: 11%

Black African: 5%

Indian: 5%

white: 3%

Black and minority ethnic men have much higher unemployment rates than white British men.

Statistics taken from the Runnymede Trust 2020 report The Colour of Money

Destructive legacies

The ethnicity pay gap did not emerge in a vacuum, but in the context of the way in which money has been made over centuries. This traces back to historic injustices such as slavery and colonialism, which led to some people becoming disproportionately wealthy at the expense of others.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade contributed enormously to the wealth of Britain. Many institutions – including the Bank of England, Lloyds of London and the Church of England – had links to chattel slavery through their activity or investments. When abolition came in 1833, the British government borrowed £20m to compensate slave owners, which was one of the largest loans in history. It was just eight years ago – in 2015 – that British taxpayers finally finished paying off this debt.

In the face of abhorrent exploitation, our Christian faith speaks of a God of justice

Analysis by the Bank of England has shown that ten individual bank accounts were credited with compensation totalling £2.2m. Some of these were partners in London banks and merchant firms that had pre-existing ties to the colonies. “All of this provides further evidence for the strong links between financial institutions in the City of London, the capital generated through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and the compensation process during the 1830s”, declares a research paper on the Bank of England’s website.

Conversely, transatlantic slavery created negative legacies for the millions of people who were exploited, and their descendants. Generations were separated from their families, tortured, raped and forced to work for the enrichment of others. Activists campaigning for a better understanding of the legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade point to the brutal experience as a source of trauma for many people of African and Caribbean descent, as well as the huge economic cost to those who were forced to work for nothing under slave masters – and who were never compensated when abolition finally came.

In order to justify their practices, the proponents of slavery institutionalised ideologies of racism – particularly that people of African descent were less than human – and this racism continued long after the Transatlantic Slave Trade came to an end. Caribbean migrants who arrived in the UK in the 1940s and 1950s were descendants of enslaved Africans and faced their own discrimination and financial exclusion. They were often unable to obtain loans from banks, meaning they struggled to buy homes and were forced to establish practices such as ‘pardner’ or ‘su-su’ in which they would pool their money. Such schemes still exist, and are evidence of how the inequalities that began with slavery endure today.

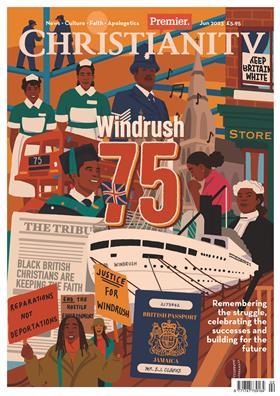

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the arrival of Empire Windrush, the ethnicity pay gap is an important example of the ways in which race and money are intertwined. In the face of abhorrent exploitation and the distortion it creates in our world, our Christian faith speaks of a God of justice, a God to whom everything ultimately belongs, and a human race made – each and every one – in his image, dignified and equal in his sight.

Just Jesus

Many of Jesus’ encounters and stories point to a more just use of money. He tells a rich man to sell his property and give to the poor, stating that it is “easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25). He tells the story of a rich fool who should have stored up treasure for God and not for himself (Luke 12:13-21) and, on becoming one of Jesus’ followers, Zacchaeus the tax collector gave away half his wealth (Luke 19:8).

The Bible recognises the connection between wealth and the build-up of inequality and injustice. Prophets such as Amos focus our attention on the immorality of those who impose taxes on the poor or who practise corruption (Amos 5:11-12). New Testament writers such as James warn the rich that “the wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you” (James 5:4). In Leviticus, God ordains a jubilee for his people in order to reset debts and ownership of assets, and give people a clean slate, which reduces inequality and the effects of injustice. Then Jesus, when he announced his ministry, proclaimed it a year of jubilee – of freedom and good news for the poor (Luke 4:18-19). We need to consider how wealth has accumulated in our society. Where this is rooted in injustices such as slavery and racism, we must consider what we can do to redress it.

How can I bridge the gap?

AGM activism is one way Christians can play a part in racial justice. Asking questions at the Annual General Meetings of FTSE 100 companies is a great way to hold companies to account. If you buy a nominal share in a company, or are ‘lent’ a share, you can ask a question of its leadership in an open forum. This provides the opportunity to expose issues such as the ethnicity pay gap. It’s a great way for Christians to “speak up and judge fairly” (Proverbs 31:9).

Closing the gap

The way money is used in our world is often a reflection of a less-than-human way of relating to each other. We treat people as objects, commodifying and monetising them. The ethnicity pay gap distorts the truth that we are all made in the image of God and equally loved by him. Even where discrimination by employers is not the cause of the gap, systemic injustice undoubtedly plays a part. Employers that practise transparency by publishing information on the pay received by all their staff offer a sure-fire way to shine a light on inequality. They must then set out the concrete steps necessary to close any gaps.

This article might be the first time you’ve heard of the ethnicity pay gap. My prayer is that you would not hide from its uncomfortable realities, but that we would work together to reveal the truth and better understand how situations come about – even when those situations might be difficult to face. Then we can work together for a society where everyone is valued as equal, where we seek to glorify God through our economic and financial endeavours (as in every other area of our lives), and where “justice [rolls] on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream” (Amos 5:24).

This article was published in our Windrush 75 special issue of Premier Christianity. Subscribe for half price

No comments yet