Walt Disney attributed his success to a daily habit of prayer. But now, as Disney celebrates 100 years of family fun, Christians are divided on the merits of the entertainment giant. Is it still the home of good, clean entertainment or should we be suspicious of its political stances?

1. Ubiquity (noun) – the fact of appearing everywhere

As The Walt Disney Company celebrates its 100th year in business, there may be no more appropriate word to sum up the multimedia mega-brand and its influence. Its grasp on culture, and particularly on the hearts and minds of children and young people the world over, is unprecedented. From movies to TV shows (and channels), toys and video games to theme parks, Disney isn’t just the biggest player in media; it’s now the Goliath that turns every other contender into a David. Like Alexander the Great, Disney’s executives must sometimes weep that they have no worlds left to conquer.

Shareholders, meanwhile, lean back in their pool loungers and rejoice. A relentless series of takeovers and diverse project launches has seen Disney become one of the largest entertainment companies in the world, recently valued at $183bn. In 2006, they purchased their rival, Pixar; in 2009, they acquired Marvel Entertainment. And, in 2012, almost unthinkably, they bought Lucasfilm, owners of the Star Wars franchise. As expansions go, it has been audacious and barbaric, and has allowed Disney to push its way into an ever-greater number of cultural avenues – and homes.

Yet for most of the last 100 years, endless expansion, world domination and even extraordinary profits were not the main drivers for the House of Mouse. And that is because it was established by one of the greatest dreamers of all time.

2. Outlier (noun) – a person or thing differing from all other members of a particular group or set

Walter Elias Disney, a Chicago-born illustrator from a modest family, spent his teenage years drawing patriotic cartoons for his high school newspaper. Unable to join up and fight in the first world war because he was too young, Disney forged his birth certificate and became an ambulance driver for the Red Cross. He arrived in France just after the fighting had subsided, but the story gives an early insight into a creative brain that was short on fear, and happy to take risks and bend the rules.

WALT WAS PROBABLY A CHRISTIAN TEENAGER

When he returned from Europe, Disney worked as an artist and illustrator, but soon began to launch his own ventures, experimenting with the emerging field of animation. His early efforts yielded modest but promising successes – a series of short cartoons called Laugh-O-Grams, which both honed his skills and got him noticed. By 1923, he had moved to Hollywood and, with his brother Roy, he launched Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio. He was 21 years old.

It’s too obvious to say that without Walt Disney, the entertainment company would not exist. But more than that, the world would have been deprived of so many works of art and culture (and perhaps, even more significantly, a raft of innovative breakthroughs) had young Walt forged his birth certificate a little earlier, and caught a bullet on the Western Front. Perhaps someone was looking out for him.

3. Zeal (noun) – great energy or enthusiasm in pursuit of a cause or an objective

The faith of Walt Disney seems to be a matter of some debate. The 2004 book The Gospel According to Disney: Faith, trust, and pixie dust (Westminster/John Knox Press) cast the eponymous genius as a broadly religious but not specifically Christian man who never allowed any personal faith preferences to impact his productions. “The Gospel of Disney is all about me”, wrote the book’s author, Mark Pinsky. “My dreams. My will. ‘When you wish upon a star, your dreams come true.’ The Disney bible has but one verse and that’s it.” Pinsky argued that there is “scarcely a mention of God” in the litany of feature films produced before or after Walt’s death.

Pinsky’s critique is familiar, and consistent with that of many who paint Disney (the company and the man) as a broadly moral purveyor of humanist ideology. It’s all about searching your heart, finding the hero within and overcoming evil with good to make all your dreams come true. Christians tend to flinch at such thinking, perhaps understandably.

older Disney films perpetuate outdated and racist stereotypes

Yet Walt himself seemed to believe something quite different, at least if we rely on the 1949 article that he wrote for the Judeo-Christian spiritual magazine, Guideposts: “I was grounded in old-fashioned religious observance”, Walt wrote. “My people were zealous members of the Congregational Church in our home town, Marceline, Missouri. My father, Elias Disney, who was a contractor, built our local church and was a deacon of the congregation. I was baptized there and attended Sunday School regularly.” So it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that Disney junior, the brilliant young man whose morality urged him to join the good fight and whose acumen enabled him to launch an entertainment megalith, was probably a Christian teenager.

That wasn’t the end of it though. The Guideposts article – which was bizarrely illustrated with a cartoon of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck going to church – described an adult spirituality built on two pillars. First, Walt believed in a moral lifestyle demonstrated through good works: “All I ask of myself is to live a good Christian life”, he wrote: “Deeds rather than words express my concept of the part religion should play in everyday life.” Second, and perhaps more interestingly, Walt believed in the centrality of prayer, adding that: “A prayer, it seems to me, implies a promise as well as a request; at the highest level, prayer not only is supplication for strength and guidance, but also becomes an affirmation of life and thus a reverent praise of God.” Deeds inspired by Christ; prayer that brings reverent praise. Maybe Walt wasn’t an evangelical, but he certainly identified as a Christian.

4. Woke (slang) – aware of and actively attentive to important societal facts and issues

Long before Pinsky wrote his book, Disney had been a fairly consistent target of criticism from conservative Christian leaders and commentators. More recent controversies include the inclusion of LGBT characters and storylines, such as the character of LeFou in the 2017 live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast. But moral panic around the company’s movies is nothing new; concerns were raised around the use of witchcraft and magic in films like The Little Mermaid and, before that, Cinderella. The alleged sexualisation of certain characters, such as a bikini-wearing mermaid Ariel, have been cited as contributing to society-wide moral decay. And alongside the criticism that Disney promoted a humanist replacement for gospel-centric morality came a nagging concern that, where religious figures were shown on screen, their portrayals were always negative, such as the self-righteous Frollo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

In the last few years, though, focus has switched to Disney’s apparently-liberal politics. Loud voices in the American evangelical movement, such as Franklin Graham, have called for boycotts; the conservative worship leader Sean Feucht has led protests outside Disney’s corporate HQ. Their main concern: that The Walt Disney Company – which now has its tendrils in every corner of family entertainment – is actively promoting a certain view of gay and trans rights. Last April, Graham tweeted: “Today, Disney is indoctrinating children w/the LGBTQ agenda – & they don’t try to hide it. I hope parents wake up to what Disney is trying to do & protect their children & grandchildren from the lies this once-great company is now so willing to promote.”

There are many Christians who feel negative – even combative – towards the company on the basis of its current politics

Conservative media outlets such as Fox News have also expressed concerns about the addition of content warnings to older Disney films that perpetuate outdated and racist stereotypes. Fox commentator Laura Ingraham claimed that: “literally no-one” noticed these tropes before Disney’s disclaimer, adding: “When are they going to start worrying about the beleaguered conservative Christian class? Where do they go to get their changes and their apologies and their warnings?”

Walt Disney might have believed in Christ-imitating deeds and the centrality of prayer, but today, a number of Christians believe the company he founded is leading the world’s children astray. And for them, that’s enough to turn Disney into an enemy. A tool of the enemy. It might have created the first feature-length cartoon (Snow White, 1937) and one of the first-ever theme parks. It may have pioneered technological developments, including the ground-breaking shift into 3D animation, and inspired millions of other innovators and storytellers to develop their own ideas but, as social media would tell it, #DisneySoWoke. In spite of all the good it might have brought to the world, some fear that the company is trying to tear our culture apart.

5. Innovation (noun) – The act or process of creating a new method, idea or product

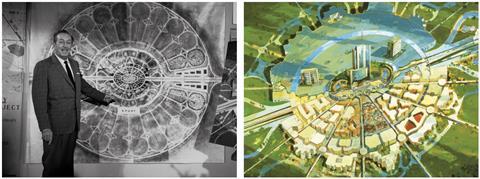

In 1966, Walt Disney announced his most ambitious project ever. The ‘Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow’ (EPCOT for short) would be a whole new American city, built in a huge, Disney-owned Florida location. If successful, the 20,000-resident community would serve as a blueprint for future urban planning. Walt’s dream – no doubt inspired in part by a faith that worked itself out in action – was to address some of America’s biggest societal challenges. Far from trying to tear the country apart at the seams, his greatest dream was apparently to mend it.

The EPCOT idea was remarkable in its sheer size and imagination. Homes would be cutting edge but affordable; pedestrians would be prioritised but transport made swift and efficient. New technologies would be developed and piloted on a consistent basis; international boundaries would be blurred and diverse cultures celebrated. The whole thing was designed to centre the concept of environmental sustainability – and this was in 1966. It was a utopia, and it wasn’t about the money.

Sadly, 1966 was also the year that Walt Disney died. Stripped of its visionary, the company quickly lost its taste for global community transformation, and focused once more on making great animations. They did it well. In 1967, they released The Jungle Book. More than 50 years on, they’re still filling cinemas and theme parks.

A Christian response

What then, is a Christian perspective on Disney? Just as there is no single strain of Christian theology or thought, it’s difficult to provide a blanket answer, especially when we’re talking about one of the most diverse organisations on the planet. There are many Christians who feel negative – even combative – towards the company on the basis of its current politics. Yet there is another group who find no quarrel with Disney or its output; either seeing enough touchpoints in it’s catalogue of stories to provide connections into the gospel itself, or simply believing that while Disney isn’t explicitly ‘Christian’, it’s doing little or no harm.

What perhaps does deserve a revisit is our view of Disney’s mercurial founder. In 2004, Pinsky cast Walt as a humanist wolf in a generically religious sheepcloth. “Walt’s religion’,” he wrote: “was built on the unfailing American belief that virtue and hard work will make all your dreams come true.” I’m not sure that was fair. Walt himself wrote that “whatever success I have had in bringing clean, informative entertainment to people of all ages, I attribute in great part to my Congregational upbringing and lifelong habit of prayer.” Walt walked and talked with the Lord, but commentators like Pinsky perhaps didn’t like what they came up with together.

WHATEVER SUCCESS I HAVE HAD, I ATTRIBUTE TO MY LIFELONG HABIT OF PRAYER

Of course, Walt was no saint. Allegations of antisemitic beliefs and associations refuse to completely disappear, although it’s important to underline that these were unproven and strenuously denied. He ended up at odds with many of his workforce during wartime labour disputes. He has been accused of mismanagement, discrimination and even participating in espionage. He is clearly one of modern history’s more complex figures, and the continued spotlight brought by having one of the most famous surnames in the world means that his story will be raked over for generations to come. Whatever else is true of him though, Walt was a believer.

At 100 years old, Disney continues to inspire and delight – and, to some degree, innovate. The focus for now seems to be on world domination, but there arguably haven’t been too many ‘great’ Disney films since the turn of the current century. Perhaps it would make sense for those running the company today to rediscover their founder’s passion for creativity, people and community building. But rather than simply critiquing another capitalist megalith (because honestly, there are plenty who deserve that), I think that we in the Church should draw similar inspiration, and celebrate Walt Disney, the Christian pioneer.

No comments yet