The numbers of people participating in the post-Christmas detox has grown exponentially. Emma Fowle finds out what it’s all about and looks at whether Christians should get involved

Ten years ago, Emily Robinson made a New Year’s resolution to run a half marathon. In the haze of a post Christmas blowout, quitting the booze for a month to help with her training seemed like a good idea. And it was. She slept better, lost weight and everyone wanted to talk to her about her month of sobriety. After taking up a job at Alcohol Change UK, her self imposed detox caused a stir among her new work colleagues. Eventually, in 2013, with the help of journalist and former alcoholic Alistair Campbell who backed the campaign, Dry January was born.

The popularity of the challenge has exploded since then. Four thousand people signed up in 2013. This year, an estimated 6.5 million people will take part – that’s one in five people who drink alcohol, and one in eight of all UK adults. Academics have got on board too and confirmed that a month off the booze is helping people lose weight, reduce liver fat, cholesterol and blood sugar levels, and can even lead to healthier drinking patterns for the rest of the year.

REASONS TO GO DRY

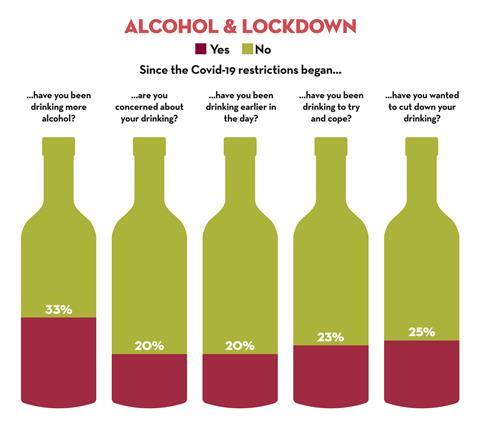

People’s reasons for participating in 2022 will be more varied than ever. When surveyed, one in three said they had drunk more often during lockdown, and one in five were concerned about the amount they had been drinking since Covid-19 restrictions began. A similar proportion said they had been drinking earlier in the day than before, with 23 per cent reporting they drank “to try and cope”. One in four people said that they wanted to cut down on the amount of alcohol they consumed.

But surely no Christian would fall into any of these categories? Surely we, as paradigms of self-control, would never drink more than we should (even at home, where no one can see) or fall into the habit of relying on a large glass of Pinot (or three) to unwind at the end of a heavy day?

It’s unrealistic to assume that an issue like alcohol dependence, which affects one in five people, never affects those with a Christian faith. Just as porn is a problem for Jesus-followers and abuse happens inside the Church as well as outside it, we can be sure that at least some Christians also drink more than they should. Despite what outdated stereotypes suggest, the younger generations are actually drinking less. The biggest drinkers in our society are the middle-aged, middle classes. In short: your typical churchgoing demographic.

A CHEQUERED HISTORY

From the time that Jesus turned water into wine, the Church’s relationship with alcohol has been complicated. Medieval monasteries were some of the earliest adopters of brewing techniques, often using the profits from selling alcohol to feed the poor. Arthur Guinness was a devout Christian who created his eponymous beer as an alternative to stronger, more dangerous spirits that were causing devastation at the time. But through the ages, Christians have also been some of the most vociferous critics of the ‘demon drink’ (a term that first shot to popularity with temperance campaigners in the 19th Century), with William Booth and Charles Wesley advocating for total abstinence. It is still a divisive issue within American evangelicalism today, creating rifts between churches, families and Christian institutions.

Historically, many of the major UK denominations (including Baptists, Methodists, the Salvation Army and Quakers, as well as many evangelical and Pentecostal church movements) would have banned or heavily dissuaded its membership from drinking. But this attitude has softened in many parts of the Church. Unthinkable just a few decades ago, it is now common for many churches to serve alcohol at social or outreach events, for leaders to drink openly and for some Christian festivals to have bars and pubs onsite. And when was the last time you heard someone teach on alcohol consumption?

MOST ADULTS DON’T KNOW HOW MUCH ALCOHOL CONSTITUTES BINGE-DRINKING

DRINK AND DISSIPATION

Whether you believe the Bible prohibits alcohol entirely or not, its stance on drunkenness is clear. “Do not get drunk on wine, which leads to debauchery. Instead, be filled with the Spirit,” says Paul in Ephesians 5:18. God’s immediate alternative to drunkenness is not a command to abstain from alcohol, but to be filled with something else: the Holy Spirit. For a kid who found Jesus in the 90s evangelical church movement, seeing people ‘drunk in the Spirit’ was a fairly normal occurrence. I can remember helping my parents, newly born again, and another couple from my church across the Butlin’s site after a particularly raucous evening at Spring Harvest; four adults swaying wildly and laughing as if they’d spent the evening downing shots, not worshipping God.

There are those who are sceptical of such experiences, but it is worth remembering that this is not the only time that the Holy Spirit’s presence in a person is compared or confused with the effects of alcohol. Consider Pentecost (Acts 2:13) when, after being filled with the Spirit, the disciples began to speak in tongues and some accused them of being drunk. Or Eli, who, on seeing Hannah praying fervently in the temple, assumed she had been drinking (1 Samuel 1:13-14). Is it possible that, like most of the devil’s tricks, alcohol is simply a poor imitation of that which God’s presence gifts us perfectly?

Shouldn’t a life lived with Jesus deliver a sense of fun and freedom; increased confidence in who we are and what we’re capable of; a lack of fear and inhibition and a welling up of love and a bubbling over of joy? On the Instagram feed of a friend, I recently read: “Sobriety delivers what alcohol promises.” Wise words, but perhaps they’d better read: “The Holy Spirit delivers what alcohol promises.”

Different translations of Ephesians 5:18 warn that drunkenness will “ruin your life” (NLT), lead to “reckless indiscretion” (the Berean study Bible) or, simply to “dissipation” (NKJV). And it’s this last one that worries me the most. Most Christians (especially those of a certain age and life stage) are not likely to indulge in the kind of drinking that results in wild, tempestuous affairs, disgracing yourself at the office party or getting in a punch-up at the local boozer. But the devil is a wily fox, and the Christian life can just as easily (or perhaps even more easily) be derailed by quiet dissipation as full-blown alcohol dependency. It is this point which challenges my own attitude to alcohol the most.

SOBER AND ALERT

Recently, Carl Beech, evangelist and leader of Edge Ministries, announced his intention to take a break from the booze. It was an experiment, he said; an ongoing discussion with God. He’d been challenged by the work he was doing among poor and marginalised communities – like Booth, he saw the destruction caused by alcohol addiction – and wondered if God was calling him to take a stand against it. But more than that, he added, he felt a stirring to sharpen his focus, to be, as Peter challenged the early Church, “alert and of sober mind” (1 Peter 5:8). In his interview with Premier Christianity last month, Beech said there was, in his opinion, “endemic alcohol dependency in the Church”. Just a few hours after that conversation, the evangelist set up a Facebook group and Twitter handle (@soberleader) to encourage safe discussion among Christian leaders who wished to reduce or stop drinking alcohol.

THE CHURCH’S RELATIONSHIP WITH ALCOHOL HAS BEEN COMPLICATED

For most of us, our drinking habits won’t lead to blackouts, or constitute that which would normally be considered problematic. But whether it’s relying on a glass of wine to lift the tensions of the week, or “needing” a beer to take the edge off a social situation, there are many (often small) ways that booze can affect our spiritual life. A drink or two may not be enough for us to consider ourselves drunk, but it might prevent us from spending time with God in prayer before we go to bed, or from getting up in the morning to read our Bible. We may not like to admit it, but even moderate amounts of alcohol may make our tongues looser, cause us not to be such a great witness, or leave us feeling less than sober-minded and less able to communicate with God.

IT’S COMPLICATED

Hailing from a sprawling East End clan, our family celebrated every special occasion like it was an episode of the famous soap opera. Anniversaries, birthdays and weddings ended, on a good night, with a raucous rendition of ‘Oops upside your head’ and great-uncle Dave attempting a benign striptease or, on a bad night, a bit of aggro outside in the car park.

Exercising abstinence allows us to master our desires and appetites

When I became a Christian in my teens, I was the first in my family to find Jesus. Growing up in Essex, I cut my teeth on K Cider and MD 20/20. By the time I got to university, as Sara Cox was blazing a trail for ladettes everywhere, I’d discovered my ability to hold my booze and carry four pints back from the bar was a sure-fire way to win approval and acceptance. Once at work, the pattern continued: full days in the office, long nights in the pub. My colleagues knew that I believed in Jesus, and I justified my (heavy, social) drinking by offering up excuses: people said I wasn’t like most Christians they knew (which was obviously a good thing!); I had great conversations with people about God in the pub, and I wasn’t a fighter, puker or a crier. In short, it wasn’t like I disgraced myself, so surely it was fine?

My husband and I met around this time and our courtship was largely played out over a pint of beer (or five) and a late-night curry. He had grown up attending church but had yet to have a personal relationship with Jesus. I had known that relationship but was not, at that time, living a wholly Christian lifestyle. As we got married and started to go back to church regularly, we made a pact: let’s stop drinking so much on a Saturday night, we said. That was our first baby step towards honouring God when it came to alcohol. Also, listening to someone play the drums ten feet away from you on a Sunday morning when your head is pounding from the night before is enough to put anyone off booze.

NO CONDEMNATION

Many years later my relationship with alcohol, and my response to it, is still a work in progress. And if the popularity of Dry January, and the response to Beech’s ‘sober leader’ call to-arms is anything to go by, I am not alone.

As with many areas where we might struggle, the typical Christian response is often to ignore or deny. “There’s no problem here!” we cry, while dealing with yet another young Christian leader who drank too much at a party. “I don’t drink that much!” we exclaim, writing off the mounting empties in the bin (again) as “no big deal”. Research has shown that when asked, most people consistently underestimate the amount they drink by up to a half. More than 60 per cent of UK adults have no idea how much alcohol constitutes binge-drinking. (If you’re a woman its six units in a single session. That’s three pints of lager or two large glasses of wine. For men its eight units.)

Playing down the amount of alcohol we consume misses the opportunity that looking at the issue soberly (excuse the pun!) presents. “Who can discern their own errors?” asks Psalm 19:12. It’s hard but, as Christians, a time of reflection, recalibration and moderation is never a bad idea – especially as we enter a new year. Self-control is a fruit of the Spirit, and taking the opportunity to develop it is always good. Exercising abstinence, even if just for a time, allows us to master our desires and appetites, rather than have them master us – just as we do when we fast from food, give up TV or quit coffee for Lent.

Thomas Aquinas once said: “No one can live without delight, and that is why a man deprived of spiritual joy goes over to carnal pleasure.” Perhaps, as Paul points out in Ephesians, without the joy brought about by the presence of the Holy Spirit in our lives, Christians (including those in leadership) are as susceptible as the next person to finding solace, comfort, relief or temporal happiness in a couple of glasses of wine or a few pints of beer. If drinking two large glasses of wine is classed as binge-drinking, how many of us would fall into that category, at least occasionally?

For some, Dry January is an opportunity to recalibrate a relationship with alcohol that has got a little out of whack. For others, it may be a health-based decision, or a whisper from the Holy Spirit to sharpen our spiritual life; to be more alert and sober-minded. For some, it may be a gentle reminder to not rely on booze for that which should, ultimately, come from God. But whatever your reasons, if you are one of the many millions of people taking part this year, let’s do so honestly and openly, with the Holy Spirit’s help, knowing that, despite what we may feel or others may say, there is “no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1). Let’s take this opportunity to be filled with the Holy Spirit and the true joy that only he can bring.

100% Appetising 0% Alcohol

Looking to cut down? Here’s our round up of the best Low/No alcohol alternatives:

Nozeco

A gently sparkling drink based on de-alcoholised wine (less than 0.5% ABV), this was a firm favourite among the Premier Christianity testing group. Not as dry as Prosecco, it is nonetheless much less sweet than other grape-based fizzy drinks such as Shloer, and has the added benefit of looking much more sophisticated when placed on the table. It’s not prosecco, but it is refreshing, with hints of elderflower. Suitable for vegans.

Pentire

A non-alcoholic, plant-based spirit made in Cornwall, Pentire’s ingredients list includes samphire, sage, citrus and sea salt. With no added sugar or preservatives, it may appeal to those who want a natural, non-alcoholic drink that isn’t laden with sugar. Pour it long and high over tonic and ice and you’ve got an easy-drinking, grown up alternative to the G&T.

Brewdog Punk AF

Advertised as alcohol-free (AF), technically, at 0.5% ABV, this drink is a low alcohol version of Brewdog’s flagship IPA, Punk. Rather than removing the alcohol after fermentation, the recipe used is low in fermentable sugars, resulting in a hoppy, floral beer that provides a palatable alternative to other amber ales. Contains lactose, so not suitable for vegans.

Becks Blue

At less than 0.05% ABV, Becks Blue is classed as a no-alcohol lager. Very light in colour, this pilsner-style beer accounts for more than a third of all alcohol-free beer sales in the UK and is an inoffensive easy drinker with no strong aftertaste. It also conforms to German beer purity laws, meaning that, unlike many other mass-produced alcohol-free beers, its ingredients are all natural and suitable for vegans.

Lucky Saint

Another low alcohol beer (0.5% ABV), Lucky Saint is an unfiltered beer that is also brewed in Germany (meaning all-natural ingredients and suitable for vegans). It is fermented for 42 days before having the alcohol removed, which results in a darker, maltier taste with a slight bitterness that’s more like a cask conditioned ale. If you like a bit more of a yeasty mouthful from your beers, you may enjoy this one.