The angry atheism once popularised by Richard Dawkins is now widely considered to be just as dogmatic as fundamentalist religion. But with growing numbers of people preferring a gentler, more agnostic approach to faith, Andrew Sach and Jonathan Gemmell explore how we can best reach the fence sitters

In 1998, the British social attitudes survey found that 17 per cent of the population thought of themselves as non-religious. By 2018, this had risen to 44 per cent. Yet, as eminent church statistician Peter Brierley recently said: “Explore more deeply what those who are non-religious believe, and you will find that a surprising percentage believe in ‘religious’ things.” For example, 47 per cent think of themselves as spiritual; 35 per cent believe in a higher power; 34 per cent believe in life after death. People believe in something, but they don’t want to be pinned down to a particular faith.

The word agnosticism comes from the ancient Greek gnosis, meaning ‘knowledge’. The a at the start of the word just means ‘not’. We say something is ‘atypical’ when it is not typical, or ‘asymmetrical’ when it’s not symmetrical. You could call a vegetarian an ‘acarnivore’, or someone who doesn’t like bagpipes, ‘aScottish’, perhaps. If gnosis is about knowing, then agnosticism simply means not knowing. And not knowing, at least when it comes to religion, is becoming increasingly popular in our society today.

Perhaps we are right to be concerned about any belief to which another human being is so passionately committed that they are willing to die for it (and in some cases, kill others too). Terror attacks, extremism and the innumerable ‘religious’ wars waged over the centuries show enthusiasts can be exclusive. Dogmatism is dangerous. Creeds can be cruel. Believers can be blinkered (and anything can be alphabetised). It seems that many are wary of the excesses of any belief system and prefer, instead, to identify as humble agnostics. They are just not sure.

You’d think that sitting on the proverbial fence indefinitely would be uncomfortable, and it is, though with a bit of DIY and some memory foam it can be quite bearable. The comedian Marcus Brigstocke puts it like this in his book, God Collar (Corgi): “The truth, as I see it, is that I would rather stay in a place of confusion amongst similar restless souls shuffling about in the hope there might be a sign pointing in one direction or another, than leap aboard whichever bandwagon looks like it’s got some momentum behind it and a confident driver. We might find God. We should probably have a plan for that in case we startle him and he goes for us. I don’t mind if we don’t find him. I’d be just as happy to discover that whatever road this is that I’m on, I’m not walking it alone.”

THREE KINDS OF AGNOSTIC

But before we consider how to best share our faith with those who just don’t know – or care – about God, it is worth pointing out that there are three main types of agnostic:

Type one agnostics accept that something is knowable but they just haven’t looked into it. So, for example, Jon is agnostic about how many helium balloons it would take for his wife, Aileen, to fly. It would be possible to know – a fairly simple experiment in fact – but because Aileen is afraid of heights, it doesn’t seem very kind to find out. Some people are agnostic about Jesus in this sense. They’ve never got round to reading the Gospels to discover how courageous and demanding and humble and angry and sacrificial and loving he is.

Type two agnostics are shaking their heads at this point. For them, it’s not just “I don’t know” but “We can’t know”. Theirs is a more entrenched conviction. There’s an awkward irony here, because type two agnostics aren’t very agnostic about their own position. To paraphrase, they are really saying: “I know that you can’t know.” Really? What makes them so sure that they can’t be sure?

“I know there is no compelling evidence for a God” is a bit like saying: “I know there is no treasure hidden in Leicestershire.” How could you know this? First, you would have to have dug everywhere. What if there were a gold ingot deep beneath an inconspicuous cabbage field? Or a stolen diamond necklace inside a detergent bottle at a postcode the police did not check? It turns out the University of Leicester archaeological services – who, let’s face it, do more digging than most of us – didn’t even know that King Richard III was buried under their local car park until recently.

Type two agnosticism is tantamount to claiming to know everything. Only then could they be sure there wasn’t some critical evidence that they’d missed. They’d need to know all history, to have explored every scientific avenue – including the ones we don’t even know about yet. And they haven’t. This makes type two agnosticism irrational.

Type three. That just leaves type three agnostics. For them, it’s not: “I don’t know” or: “I can’t know” but: “I don’t want to know, leave me alone.” Type three agnostics use scepticism like a philosophical handbrake, to avoid being budged from the comfort of the status quo. Agnosticism appeals not because of the fear that Christianity is not true, but because of the fear it’s not good. There’s a suspicion that God – if he’s there – would want to spoil the party, limit my choices, suck out the fun. If Christianity had a colour, it would be grey. If you could sum up the Christian ethic in a word, it would be “don’t”. Being a Christian means ill-advised fashion choices (socks and sandals), a wine cellar stocked only with Shloer (‘Christian champagne’) and replacing your favourite Netflix thriller with back-to-back repeats of Songs of Praise on VHS.

TO REMAIN UNDECIDED ABOUT MEDICAL MATTERS CAN BE FATAL, BUT TO BE AGNOSTIC ABOUT SPIRITUAL MATTERS CAN BE MORE DEVASTATING STILL

A friend of ours was surprised to read the Bible story of Jesus turning water into wine. It wasn’t the miracle that shocked him. Sure, H2O + C2H5OH + the subtle combination of tannins, catechins, flavonoids and anthocyanins can’t be done in a chemistry lab, but why shouldn’t the God who made the universe do some party tricks? The surprise was that Jesus wasn’t going around turning wine into water. Wasn’t Jesus supposed to be anti-fun? And yet here he is creating the equivalent of more than 800 bottles of Châteauneuf-du Pape to ensure a party kept going into the wee small hours.

Every Christian knows the truth is a person, and the apostle John met him, took him on fishing trips, shared meals with him. At the end of that experience, he wasn’t at all agnostic

TRUTH IS A PERSON

The White Cube gallery in Bermondsey, London, recently hosted an exhibition of 350 ten-by-eight inch paintings by Peter Dreher, the celebrated German artist. In a study of light, matter and time, he had sketched the same empty glass of water almost daily since 1974. It’s not unusual to find contemporary artists grappling with fundamental concepts about existence. And they are not alone. The shelves of Waterstones are full of musings on what it means to be human, what it means to be male or female or non-binary, where we came from, where we are going, where we are now, the nature of consciousness, the nature of meaning, the nature of language and so on.

Philosophising is normal. Telling people what happened to you is also normal. Every day, more than a billion people use social media to describe where they’ve been and who they’ve met. It’s normal to record personal experiences. It’s normal to wrestle with the meaning of life. But these two types of ‘literature’ (if we can call them that) usually exist on different planes. You’d rarely say: “Last night I met eternity in a micropub.” Or: “You’ll never guess who walked into the office this afternoon – the beginning of the universe!” That’s really not normal.

But it’s exactly what the apostle John did when he wrote a letter to some friends in Asia during the first Century: “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched – this we proclaim concerning the Word of life. The life appeared; we have seen it and testify to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us. We proclaim to you what we have seen and heard, so that you also may have fellowship with us. And our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ” (1 John 1:1-3).

As every Christian knows, the truth is a person. And the apostle John met him, took him on fishing trips, shared meals with him, travelled with him, “looked at” and “touched” him. And at end of that experience, he wasn’t at all agnostic. Something pretty convincing happened in the three years that Jesus and John spent together that banished all doubt.

NOT NEUTRAL

At this point, perhaps your sceptical friend objects that no amount of evidence would convince them of the extraordinary miracles described in the Bible. As you probe further, you discover that their mind is already made up, because of some unspoken presuppositions that they are bringing to the table. Even though they claim to be agnostic, there are all sorts of non-Christian ideas that they very firmly believe. In short, they are not as neutral as they think they are.

FAILING TO DECIDE MEANS THAT, ULTIMATELY, THE DECISION IS MADE FOR YOU

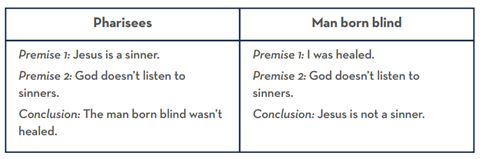

We find a darkly comedic example of this in John 9, when the Pharisees refuse to accept that Jesus has healed a man born blind, despite the overwhelming evidence presented before them (namely the blind man telling them he can now see, and his own parents confirming he was, indeed, born blind). It’s helpful to set the Pharisees’ reasoning and that of the newly seeing man side by side:

For the Pharisees, the presupposition that ‘Jesus is a sinner’ trumps the evidence of the healing, and so they conclude that the blind man wasn’t healed after all. But for the man born blind, the actual evidence of the healing trumps the presupposition, and so he concludes that Jesus isn’t a sinner after all. The man is the one being truly scientific, following the facts where they lead. In contrast, the Pharisees’ strongly held misconceptions ironically blind them to the truth.

DANGEROUS CONSEQUENCES

Imagine you receive terrible news from the doctor. It’s cancer – a pituitary gland tumour. Dr Owusu, the oncologist, recommends endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal surgery which, in plain English, means deploying a robotic knife up your nostril to cut away the malignant growth.

You don’t like the sound of this, so you seek an alternative opinion from a friend who knows nothing about medical matters: “You look fine,” she says.

At this point you have three options:

1. Put your faith in Dr Owusu. Face the surgery.

2. Reject Dr Owusu as a fraud. Dismiss the headaches and enjoy life.

3. Be agnostic. Delay hospital appointments. Reserve judgement.

In fact, options two and three are functionally the same. Failing to decide means that, ultimately, the decision is made for you. You’ve probably realised that this is a parable about the dangers of agnosticism. To remain undecided about medical matters can be fatal, but to be agnostic about spiritual matters can be more devastating still. Jesus likened himself to a doctor who had come to treat sinners (Mark 2:17). His death and resurrection are the only effective treatment, and we all need it lest we die.

If we love our agnostic friends, we’ll do our utmost to dislodge them from the fence.

Andrew Sach and Jonathan Gemmell are the authors of Are you 100% Sure You Want to Be an Agnostic? which is available from 10ofthose.com