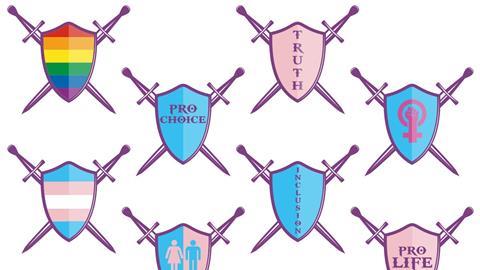

In everything from trans rights to the inclusion of gay people in our churches, people on both sides of the debate believe they’re losing the argument. Jamie Cutteridge explores why

There’s no need to fight a culture war if your worldview is in the ascendency. Christians in the Middle Ages didn’t go on crusades to lands full of churches. Upper-class men didn’t fight for the right to vote because they already had it.

So why does it feel like, in every sphere of society right now, a culture war is being fought by both sides? Why does literally everyone feel as if they are the victim?

Let’s take gender as an example. For years, people identifying as transgender have been, in various ways, an oppressed minority in the UK (and in much of the world).

People have failed to understand them; their stories haven’t been heard in the media; they’ve been ridiculed and mocked on national television. It doesn’t seem a stretch to suggest that they have been on the ‘losing’ side of this issue for much of human history.

Nowadays, we are much more aware of trans people’s stories and struggles. Mainstream media portrays them as human beings rather than problems. Rights have been extended and education has been proactive in informing young people of the breadth of people’s life experiences.

But rates of self-harm and suicide among trans people still remain disproportionately high. Many still face abuse and bullying. Members of this group, and their allies, still feel like the ‘losers’ in this particular culture war.

But so do many others. Suddenly, the existence of trans people is considered normal – and some people, many Christians included, do not really have a frame of reference for that.

For some, it feels like a direct threat. Some people worry that it makes sport unfair. Some are unsure about sharing changing facilities and toilets. Perhaps the biggest dividing line has been between the trans community and a section of feminists (including author JK Rowling) who see trans women existing in female-only spaces as unsafe and marginalising the experience of women.

The new ground broken to achieve equality for some has eroded the foundations beneath others’ feet.

Ripple effects

In an inter-connected society, it is to be expected that profound impacts for some will create ripples for others. For people whose existence was previously comfortable, the solid ground they thought they understood has shifted; their footing is a bit more uneven. And this is experienced as loss.

At times, this is turned into a political weapon that is based upon a lie. When the dominant political party wages a culture war that pits those with power, connections and money against the ‘establishment elite’, you have to ask: What’s going on here?

We saw this particularly during the Brexit debate but it has continued ever since; the latest dividing line dominating the Tory leadership contest is distilling the trans debate down to the definition of a woman, with people vying to be the most powerful person in the country, part of the government for the last decade, taking on the role of outsider.

For those in power, suggesting that they’re somehow ‘losing’ plays into a useful phenomenon. Boris Johnson’s hero is, famously, Winston Churchill. When the film of Boris’ life is made, with only culture wars rather than actual, physical wars to fight, it might look something like this:

[Scene] Meeting room in the Houses of Parliament. Squeezed inside this room are countless middle-aged white men listening to a middle-aged white man with scruffy hair. As he speaks, he has a twinkle in his eye, recalling days of old. His listeners are captivated:

Boris: “We shall fight them in the Facebook comments, we shall fight them on the evening news, we shall fight them on the Twitter fields and on TikTok, we shall fight them in the tabloids and the broadsheets. We shall never, ever surrender!”

In this playbook, admitting – ever – that you are in a position of power is out of the question. Your underdog status is your ultimate trump card.

What about us?

But what about within the Church? Speaking prior to his recent retirement, Rev Richard Coles talked about the number of churches in the UK in which “gay people are not welcome, [which] rules me out”.

While an increasing number of church denominations are now conducting same-sex weddings, or currently discussing doing so, the experience of Coles – and others in our churches – is still not the one of the inclusion they would wish to see.

For LGBT people, the process of trying to figure out what welcome they might receive before turning up to church can be painful.

It’s a very real experience of scouring church websites, trying to understand where a congregation might stand on the issues. Often, the answers are unclear.

At the same time, those on the conservative side of the Church also perceive themselves to be on the losing side of this issue. You don’t need to look far among the Church of England Evangelical Council, the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON), or whatever Calvin Robinson is saying on GB News, to see that many view the current state of the Church as being in deep peril, suffering irreparable damage at the hands of ‘loony liberals and woke wallies’. They see the Church as drifting dangerously away from orthodoxy and skirting closer the cultural norms of society.

For some, acknowledging Pride month is a way of casting aside judgement, apologising for past hurts and including rather than excluding. For others, it’s putting the values of society over the values of scripture. The same applies to gay marriages and the churches that won’t perform them; for some this values scripture, for others, it excludes. Everyone feels like they’re losing.

The way we’re wired

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised at this. According to a recent survey by Politics.co.uk, people across the political spectrum thought the BBC was biased against their own political views: “22 per cent of respondents believed the BBC to favour left-wing views, while 18 per cent perceived a bias towards the right.

Opinions likewise differ among demographics. Those over 50 are more likely to view the BBC as being too prone to promoting liberal values, whereas younger audiences view the broadcaster as conforming to a more conservative establishment.”

In the same vein, nearly everyone thinks the Google algorithm, Facebook’s moderators or Twitter’s trending topics are skewed the wrong way. Perhaps this just speaks of our human bias to gravitate towards echo chambers that reflect our own opinions?

We don’t notice the content we agree with but when we see something outside of our worldview, it jumps out and sticks in our craw.

The loser Jesus

Let’s take it back 2,000 years. There’s no doubt, by any of these definitions, that Jesus was…a loser. His country was ruled by a foreign force. His view of religion wasn’t adopted by those in power. And yet, at the end of his story, it’s those in power who seem discombobulated, killing the new man to preserve their own positions.

Despite the power balance being perfectly clear and obvious, Jesus’ status as a ‘victim’ on the wrong side of the culture war does not seem to concern him – or at least be something he considers important enough to leverage. He’s not trying to ‘win’ in any conventional way. When arguments come to him, he asks more questions than he answers. His movement isn’t focused on grasping political or religious power.

Often within the Christian world, our culture war paradigm is diluted down to biblical truth vs inclusivity. And the fascinating thing is that both sides see their approach as reflecting the ministry of Jesus.

Campaigning groups such as Christian Concern and CARE argue that, in the face of cultural norms slipping towards increasing liberalism, they and their supporters are standing for biblical truth – in much the same way as Jesus stood for truth as the religious world around him sunk into obsession over money and power.

Meanwhile, those on the more liberal wing see in Jesus someone whose ministry was defined by reaching out to those on the margins, left out by religion and society, and offering them a place to belong and thrive, irrespective of who they were and what they’d done.

The ministry of Jesus shows us the importance of balancing both of these two, seemingly opposite outcomes and motivations. Obviously, everyone thinks that the way they approach things is balanced. Perhaps, in eternity, we’ll discover that some people were right and others were wrong, but perhaps we won’t.

As a sports fan, I spend a disproportionate amount of time playing and watching sport. I love the simplicity of there being a clear winner and loser. Many of us see life through the same lens: we see politics as sport and want to see our ‘team’ win.

We see cultural and moral issues, such as sexuality and gender, as sport and are dedicated to ensuring the ‘other team’ lose. But in life – and certainly within many of today’s culture wars – there often aren’t clearcut winners and losers.

Battles may be won (the introduction of equal marriage legislation for some, the overturning of Roe v Wade for others) but the war of hearts and minds, attitudes and institutions, is much less clear.

Perhaps the balance between truth and inclusion (to use lazy shorthand) that Jesus struck is too much for any of us to truly hold. Should we, instead, be grateful that the breadth of the Church allows space for both to flourish?

Perhaps the answer to this paradigm relies not on individuals, but within Christ’s collective body. And while all of us engaged in ministry believe we are modelling ourselves on Jesus, it is important to remember that, ultimately, he was killed. In being prepared to lay down his life, he wasn’t concerned with ‘winning’, he was concerned with doing what he was called to do.

The challenge of Jesus’ ministry might look less like worrying about who is ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ the latest culture war and more like following the invitation of Jesus to do whatever we are called to do. “Take up [your cross] and follow me” (Matthew 16:24) hardly sounds like the start of a victory parade, after all.