Barbenheimer is a cinematic phenomenon. Jonty Langley has watched both Barbie and Oppenheimer, and reckons they each have something profound to say, both to the Church and to our searching culture

When Hollywood bases a film on a book, a previous film, a video game or a ride, they call it “using existing intellectual property”. I call it an endless stream of boring. I call it Deja view.

So what would you call a film based on an object created more than half a century ago that has done huge harm to our collective psyche?

I’d call it Barbie.

But you could also call it Oppenheimer.

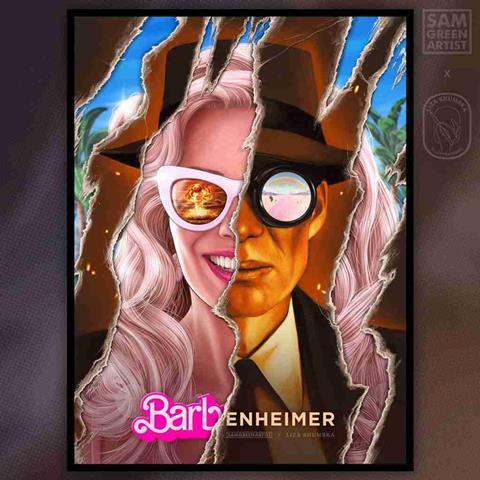

Both films are unlikely blockbusters. And yet Barbenheimer – a social media trend where audiences make a day of watching Barbie (a toyland-to-real-world Hypercolor comedy based on a plastic toy created in 1959) and Oppenheimer (a grim wartime biopic based on a uranium bomb, tested in 1945) – is a huge cultural phenomenon.

Thanks to Barbenheimer, Barbie by Greta Gerwig is 2023’s biggest film by opening weekend ticket sales ($93 million) and the highest grossing ever for a female director. And Oppenheimer by Christopher Nolan pulled in $46 million on its second weekend – great numbers even for an opening weekend, according to industry analysts, who have called Barbenheimer sales "mind-blowing".

With parties attending screenings in both 1980s pink and 1940s dour fancy dress; endless mash-up posters and Barbenheimer memes proliferating on the internet and the ‘Barbenheimer bump’ boosting both flicks beyond their individual potential, it’s worth noting that not everyone has loved both films.

In a way, that is predictable. The success of the Barbenheimer phenomenon is partly down to the fact that the films are perfectly matched and total opposites, like particles entangled at the quantum level, one spinning clockwise and the other anticlockwise, inextricably and inexplicably linked. Or, you know, like Barbie and Ken. And their fans are similar mirrors of each other.

Gerwig is an actor and director who has long been loved by women, the LGBT community, people who like to appear ‘kooky’ and indie cinephiles. You may have encountered her work in Lady Bird and Little Women. Nolan is an older and more established director, who you may know from The Dark Knight and Inception. He is beloved of self-styled ‘serious’ filmgoers who still seem to mostly watch mainstream Hollywood movies.

These are good films, saying important things, and saying them well

Like people who go to Greenbelt festival and those who like Spring Harvest, there are some people who build their identity on their preference, but generally the audience for each is much broader. There is overlap. Similarly, Gerwig and Nolan are both great writers and directors, so any stereotyping or siloing of their fanbases will be oversimplification.

If, however, you interrupted a film bro as he mansplained Fight Club to his girlfriend and asked for his top four go-to reliable contemporary directors, Nolan would be in there. And, if you accosted a bisexual Gen-Z hipster at a vegan eatery to ask the same, Gerwig would come up. Which is why it’s phenomenal to see these worlds experience a kind of cultural fusion. And possibly why it has been so explosive.

A more likely reason, though, is that Déjà view we’ve all been feeling. Because, despite being based on weird mid-century objects, Barbenheimer’s constituent films are not just ‘more of the same’ like the ECT of superhero films or Pixar flicks about things with feelings. They are far from natural choices for blockbuster material.

Consider Oppenheimer. Sure, war movies can be enjoyable, even inspiring. But nuclear war movies? Not so much. The bleakness and totality of the prospect of nuclear holocaust offers fewer opportunities for the heroic self-sacrifice and redemption arcs we love, because, if everybody is going to be killed, there’s really not much point. So Oppenheimer, with its inherent handicaps of being a scientific biopic and focusing on a man whose work led to the death of as many as 210,000 human beings, could have put many people off.

And Barbie arguably had even more to overcome, because empathy and fear do animate us, but ideology and fashion tend to interest us more.

Barbie (the toy) has been popular all of its 60-odd years, with sales exceeding $1 billion per annum since 2018. But it hasn’t been ‘cool’ for a while now. Perhaps the cultural moment when this was clearest was Eurotrash Dance act Aqua’s 1997 mega-hit, 'Barbie Girl', which mocked Barbie-ness as shallow, vain and rather stupid: a "life in plastic". To be like Barbie was to be, in a word more suited to the 90s than now, a bimbo.

Before and after that, critics of the world’s most popular doll, despite its broadening into body-positive, ethnically diverse and less ableist characters, have been many.

The main reason, of course, is her looks. So far, so patriarchy, you might say. And you’d be right, sort of. Controlling and criticising the presentation of women is an obsession of patriarchal men (and the women who enable them), for sure. But in this case, the criticism of this representation of womanhood came form a different source and had a different focus. It’s not that Barbie wasn’t feminine enough or trying hard enough to be beautiful (and therefore attractive to men), it’s that she was too beautiful, trying too hard.

A strong case can be made (strong enough to be repeatedly addressed in Gerwig’s film, which carries Mattel’s full, if deeply postmodern, blessing) that Barbie caused cultural and psychological harm by presenting young girls with not only a biologically unattainable standard of beauty (Barbie has a woman’s features, not a girl’s), but a statistically unattainable one as well (very few women have Barbie’s particular proportions).

Add to these factors a growing cultural discomfort with gendered toys and the dawning awareness of the dangers of plastics, and Barbie was far from a sure-bet as a box-office smash.

And yet, despite the odds stacked against them, and thanks at least in part to the Barbenheimer factor, the films have been wildly successful. But does that mean they’re good?

I think it does. I think it does. Moviegoers consume a lot of garbage (physically and aesthetically), but viral success can’t be sustained unless there’s something resonating with an audience. You can douse a film in marketing money, but that won’t necessarily ignite the word of mouth. These are good films, saying important things, and saying them well… (Spoilers ahead)

Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer is brilliant. Brilliantly written, beautifully shot and edited, with even an impressive sound design (for which it will surely win one of its many predicted Oscars). Oppenheimer should be hard to like. He’s arrogant, adulterous, neglectful of his children and politically disloyal. And yet we sympathise with his torment over what he has created and how he is subsequently treated. That’s what all plot does, of course: build sympathy for a flawed protagonist. But most protagonists don’t cheat on their wives and build weapons of mass destruction.

But Oppenheimer isn’t just about Oppenheimer. It’s about America and about the ethics of war. And mostly it is about physics. The subject of quantum physics finds reference and expression in lines of dialogue and character notes throughout the film. In quantum, light is both particle and wave, two fundamentally different and contradictory modes of being. And countless lines or dialogue and points of plot keep coming back to the paradox of irreconcilable states existing simultaneously (or in a space of probability and uncertainty). Oppenheimer himself is both a wealthy snob and a unionising socialist. A German scientist is magically British. A bomb one physicist thinks will end all conflict becomes an industry that threatens all human life.

The paradox is beautifully encapsulated in an exchange where a general scoffs at the idea that Oppenheimer might win a Nobel Prize for a bomb, and Oppenheimer replies: "Alfred Nobel invented dynamite." The quantum paradox pervades the film as does Heisenberg’s uncertainty, with decisions repeatedly made based on probability rather than certainty (with at least one big laugh at chances of universal annihilation being "near zero").

But Oppenheimer isn’t just clever and nerdy. It explores a larger and more important question.

In an early (and shockingly mostly factual) scene, a younger J. Robert Oppenheimer injects poison into an apple on his tutor’s desk. A character note that at once subverts the ‘apple for teacher’ trope of a more innocent age while showing young Oppy to be self-important, single-minded and mentally unstable. But it’s also an image encapsulating the entire theme of the film – one that Christians will pick up on quicker than most. A fruit that appears tempting but brings death as a consequence is straight out of Genesis. The fruit of the tree of knowledge (knowledge in Latin is scientia), is death for all humankind. Oppenheimer’s central question is whether scientific knowledge bears with it the responsibility for its destructive use – and whether some knowledge is better not known.

Barbie

Barbie, on the other hand, asks something even deeper.

Yes, Barbie also makes social and political commentary – on patriarchy and the impossible expectations placed on women. It does so brilliantly and hilariously, albeit in a gender role-reversal and re-reversal allegory that is harder to nail down than a quantum wave-state. It shows us both the unfairness of a world in which one gender dominates another and the uncomfortable truth that many are complicit in their domination and even happy – until they are made truly aware of their situation.

Some culture warriors have really disliked this. Barbie has been accused of ‘hating men’. It doesn’t. But I have some sympathy with nasally fragile male commentators who felt attacked by its gently savage mocking of stereotypical male foibles. It’s hard to watch. But I would encourage anyone who got angry at first viewing to watch it a second time, allowing the Spirit to convict without the emotion of novelty intervening.

Brilliant casting and relentlessly enjoyable performances from Margot Robbie (as Barbie) and Ryan Gosling (as Ken) make help to cover the hard message in a pink cotton-wool of comedy, but suddenly, in the last act, Barbie gets serious. Making good on an early set-up that could have been a throw-away Saturday Night Live sketch (where Barbie interrupts the plastic optimism of a musical number to ask "do you guys ever think about dying?"), our gal Barb is faced with the opportunity to embrace a human existence, with all the suffering that comes with it, and with death. She is faced with the question of what it means to be a woman in a world not yet made fair for women. But she also faces the ultimate question.

Barbie asks: what makes human life, which is painful and ultimately stops, meaningful or even tolerable? Its cagey non-answer is akin to a restating of the problem, but with a great soundtrack and moments of fleeting, home-video meaning, which resonate, comfort and upset in equal measure. But this is ultimately as satisfying as Camus’ quip that the problem of existence is "Should I kill myself, or have a cup of coffee?" It’s clever. It is as reasonable as most Existential philosophy. It helps a bit. But it isn’t enough.

For most Christians, the answer, of course, is that in Christ we have purpose, meaning and hope and that is enough to make up for the pain and the horror at the end. But this is not our cue to shut down discussions that Barbie prompts with spiritual bypassing and glib optimism. Barbie is an opportunity for us not only to be made uncomfortable about our complicity in patriarchy, but to truly wrestle, alongside our non-Christian friends and family, with how we can work out a sense of meaning for our lives. And just as when we think about both the promise and threat of science, we should do this with honesty, fear and trembling.

Barbenheimer is joyfully valuable because it is (they are) great art. But it also presents a cultural moment for conversation and witness, and to let justice roll like a river through our world.

No comments yet