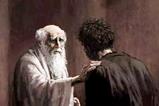

Sin has imprisoned us in a fallen world, says David Instone-Brewer. But one day, Jesus will return to set the captives free

Preachers are always looking for ways to describe the extraordinary work of Jesus on the cross: he dealt with our sins, rescued us, defeated the enemy and gave us a pardon that opens heaven’s door for us. We normally rely on the wide range of images in the New Testament that portray the various parts of his achievement, though over the years we’ve come up with many more illustrations.

For example, following the second world war, preachers sometimes depicted the cross as “God’s atomic bomb” which completely defeated the devil (Colossians 2:15). Just as a few Japanese soldiers refused to surrender after the bombs fell, the devil’s forces still prowl (1 Peter 5:8). The cross ensures the final victory, but there’s still mopping up to be done.

Anselm, in AD 1100, introduced a new illustration that became very influential. He picked up the image that Jesus paid the price for our sin (as in 1 Peter 1:18-19) and turned this into a medieval payment of ‘satisfaction’. This was the legal term for ‘compensation’ which rulers could demand from those who insulted or dishonoured them. Anselm reasoned that we dishonour God by refusing to obey and exalt him. Because God is so great, the satisfaction owed him is too large for any human to pay – so Jesus paid it for us. Before Anselm, the payment was pictured as a redemption to buy us back from slavery (Romans 6:16-18) or from imprisonment by the devil “who has taken them captive” (2 Timothy 2:26), but ‘satisfaction’ brought this up to date. Today we’d perhaps speak about a ‘fine’ instead.

Victory over evil

The most difficult aspect of the cross to explain to people today is Jesus’ defeat of the devil and his angels. Although many non-Christians believe in spirits and curses, Christians tend to avoid mentioning spiritual evil. Even the Lord’s Prayer, which asks for protection from the evil one (Greek: tou ponérou) has been translated as “deliver us from evil” (Matthew 6:13, ESV) as if it means “keep us from doing wrong”.

The early Church wasn’t reluctant to talk about demons and hell. They read that Jesus went to speak with those in hell before his resurrection (1 Peter 3:18-20; Ephesians 4:8-10). This was so important to them that they included it in the Apostles’ Creed: “he descended to hell”.

I’d like to propose a new illustration: a jailbreak. When Eve and Adam sinned and everyone joined in, we were locked out of paradise – effectively imprisoned in a fallen world where many bad things happen and evil angels roam. They have limited power over us, but enough to encourage us to give in to temptation – although some people are keen to be cruel and selfish and need no prompting. These evil angels are like cruel jailors who let their human collaborators roam the jail and torment others, while they themselves mainly sit back and watch.

When Eve and Adam sinned and everyone joined in, we were locked out of Paradise

Even though he’d done nothing wrong, Jesus chose to join us in jail and suffer with us. When the evil jailors recognised him, they told their collaborators to put him on death row. Before long, he was executed by crucifixion in the exercise yard where everyone could see.

That was a huge mistake, because now Jesus wasn’t constrained by his human body, and he overcame all the spiritual jailors. Jesus’ death also resulted in a pardon from God for all those who followed him. Although they were still in jail, the pardon meant that the jailors no longer had any power over them. Their chains were broken, and they became free to do what they wanted. Jesus himself broke out of the jail and said he’d soon be back with transport to take home everyone who has accepted the pardon.

Pardoned

When President Ford offered his predecessor John Nixon a pardon, many complained he’d been let off. Ford pointed out the Supreme Court said that accepting a pardon “carries a confession of guilt”. So Nixon could only avoid punishment by agreeing he’d done wrong. That’s also true of the pardon God offers us, which Paul describes as our charge-sheet nailed to the cross (Colossians 2:14). By accepting it, we agree we have sinned and we commit ourselves to trying, with God’s help, to avoid doing so again.

Jesus is taking a long time to return to the jail to take his followers home. We know why: he wants more prisoners to accept God’s pardon (2 Peter 3:9). In the meantime, the pardoned prisoners can spend as much time as they like in the prison chapel, in the dining room or gym. But some brave individuals spend time in the exercise yard, talking to the unpardoned prisoners. This could be dangerous – some of these prisoners are violent and don’t want to accept a pardon which entails admitting their guilt. But many of them haven’t yet heard that there’s a pardon available for them – even though the cross is in the middle of the yard – and some are eager to hear this news.

When Jesus does return, the corrupt spiritual jailors will be shut up in a secure jail along with those who rejected God’s pardon. Those who are pardoned will be able to start again and live, like Adam was meant to, in Paradise.

This illustration includes most of the aspects of the gospel as revealed in the Bible: the incarnation, the suffering at the crucifixion, the pardoning of sin at the cross, the necessity of accepting a pardon, the persistence of evil while we wait for Jesus’ return, and the importance of evangelism.

However, no illustration can encompass everything Jesus did for us at the cross. We won’t know the whole story till we meet him in glory and, even then, it will be something to marvel at. But the story of ‘God’s jailbreak’ may help us share what we do know.

No comments yet