One of my earliest childhood memories is standing in the back garden of our family home as my grandfather recited a prayer of committal for a dead bird we had just buried in the flowerbed. As a parish priest, my grandfather would have been more accustomed to conducting funerals of the human variety, but the memory has stayed with me as an example of his gentle nature and humane spirituality.

It was only as an adult that I came to learn more of the extraordinary history that led Rev Geoffrey S. Mowat towards a life of Christian service. A few years before he passed away, we sat down together to record the story of his life as a prisoner under the Japanese during World War Two.

In a professional capacity I was taping the interview for a radio documentary, but the experience was also a highly personal one, as it introduced my grandfather to me in a whole new way.

A new life

In July 1940, Geoffrey and Louise Mowat were a young, newly married couple, headed for a new life in Malaya. Geoff had completed training for the British Colonial Service and, despite the outbreak of war, had been posted to a district office in Malacca.

However, their early married life was soon to be interrupted by almost four years of forced separation. By 1941, war had spread to the Pacific as Japan entered the conflict, and Geoff was relocated to Singapore to join the defence of the Malayan peninsula. Despite their efforts, capitulation to the Japanese soon followed. Before the surrender, Louise was evacuated and her war story is an adventure in itself. Geoff, however, along with thousands of other men, started a new chapter of life in a makeshift jail on Changi Road.

Geoff oversaw the arrival of 21 sick men.…only one survived

Attempted escape

Remarkably, the early part of Geoff’s life as a prisoner of war (POW) is the story of a brazen escape. No barbed wire had been installed at Changi by this time. Two days after capture, having eluded their guards, Geoff and a friend named Bob Elliott simply walked out of the prison camp.

Several weeks of jungle adventure followed as the pair made their way north through hazardous terrain in a desperate bid to reach the coast and freedom, often relying upon the hospitality of the rural people they met on their way.

Their undoing came when Geoff was struck down with malaria. An attempt to procure medicine forced them to venture closer to civilisation, but they were betrayed and, after a vicious beating, became prisoners of the Japanese Army once more.

Prison life and prayer

Initially, prison life was tolerable. Geoff tells how the men would often carry out theatrical performances on a specially constructed stage to lift the spirits of the camp. Nevertheless, food was sparse and malnutrition soon began to bite.

Geoff had been a Christian his whole life, but his prison experience was to bring a new dimension to his spiritual life. He was particularly influenced by Anglican padre Noel Duckworth, who managed to obtain many concessions for the POWs, including extra food for those who had fallen ill.

Happily, their Japanese captors did not prohibit religious services. A makeshift church was erected for worship, and rice and tea were substituted for bread and wine. Apart from ‘dynamic’ Sunday services, Geoff recounts how the establishing of a prison prayer fellowship had a rallying effect on the men who met once a week and interceded for each other in the days between.

‘We made a list of prayer requests contributed by each person, and in this way I was introduced to the simplicity and the mystery, and, dare I say it, the effectiveness of this faltering step of faith,’ he explained. ‘We may have been babes in this kind of thing, but God is great, and for me this resulted in my complete freedom from malarial attacks for the following 18 months.’

Despite the limitations imposed by poor diet and imprisonment, life in Changi Prison was a relative haven of peace compared with what would follow.

In Hellfire Pass

By the end of 1942, POWs were being used as forced labour as the Japanese war effort intensified. A railway was being built for the shipping of supplies between Burma and Thailand. For Geoff and a large company of men, this meant an arduous journey to Ban Pong in Thailand to work on the construction of what would become known as the ‘Death Railway’. During our conversation, my grandfather’s recollections of this period were both vivid and emotional.

He would occasionally pause to collect himself while recounting a traumatic episode. It was not difficult to understand why so many men of his generation chose never to speak of their experiences. It took a great deal of persuasion to get him to write his memoirs in the first place, and the retelling churned up dormant memories.

Part of his time was spent with other prisoners quarrying a large cutting for the railway, which would earn the macabre name ‘Hellfire Pass’, so called because the sight of emaciated prisoners working by torchlight resembled a scene from hell. Jungle disease, illness and the effects of malnutrition were rife, yet sick men were often forced to continue with the brutal work day and night in searing temperatures. When cholera swept through the camp it quickly claimed the lives of the weakest. Their bodies were burned on huge pyres.

In total, some 60,000 Allied prisoners of war worked on the railway. Whether from brutalisation, exhaustion or sickness, more than 12,000 died during its construction, of whom almost 7,000 were British. As well as suffering the effects of malnutrition, Geoff received several beatings at the hands of the guards. One was particularly memorable because it occurred on his 26th birthday.

God in the suffering

Despite everything, Geoff still recalled moments when God seemed very present: ‘On this particular day, I don’t know why, but I was one of the last of the day shift to leave the job. As I took the jungle path home, I found myself on my own; a somewhat bizarre moment for a British POW in farthest Thailand.

‘Why ever it should have been I shall never know, but as I followed that track my spirits lightened and I found myself actually singing. Don’t laugh! It was a song from Mendelssohn’s Elijah, which I had learned at school. Could it be a sign

of God’s presence in the midst of all that suffering and misery? After all, no one else could hear me singing: “O rest in the Lord, wait patiently for Him, and He shall give thee thy heart’s desires...”’

Geoff also volunteered at the camp hospital. The work in Tent 13 was less physically demanding than on the cutting, but it meant seeing many sick men slip away before his eyes. Memories from this time include a Communion service held by the camp padre.

‘The picture is as clear as if it took place yesterday: the padre with his chaplain’s scarf, the ragged and emaciated men kneeling, if they could, to receive the sacrament of God’s love. It was, after all, a sacrament of life and of peace,’ he shared.

Sensing a new call

In the course of time, as work on the railway began to finish and because of the high mortality rate, the camp gradually began to disband. Along with other survivors, Geoff was eventually evacuated.

But the time spent at the tented hospital was formative in Geoff sensing a future call to Church ministry. In one month, Geoff had overseen the arrival of 21 sick men from another camp, all conscripts from the mining villages of Rhondda. As they were not acclimatised to tropical conditions they had quickly fallen prey to jungle diseases. Only one survived.

While Geoff was able to offer some comfort to the men, and was assisted by the padre in their final hours, he felt ill-equipped to deal with their spiritual needs.

Could it be a sign of God's presence in the midst of all that suffering and misery?

‘It was these experiences which led me to question the purpose of my life...and to wonder if the God who had preserved me so far had something more for me,’ he recalled. That sense of calling solidified as he returned to the relative normality of life in a POW camp. His new location was at a repurposed golf club in Singapore. With an improved diet and lighter physical duties, life was much improved. Here, Geoff came under the influence of several spiritual mentors. One of them, Padre Eric Cordingly, first challenged him to consider ordination in the Anglican Church.

Reunited with Louise

Geoff was finally transferred back to Changi Prison, bringing the opportunity for further conversations with Padre Noel Duckworth, as well as reading and prayer. Meanwhile, the war had decisively turned against the Japanese, with the detonation of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. By the time liberation arrived, Geoff had made up his mind that he wanted to pursue ordination. The only question that remained was how Louise would respond.

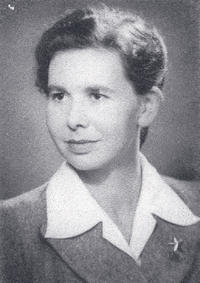

Communication between them had been sporadic during his time in captivity. Towards the end of his internment, a letter containing a photo of Louise arrived, leaving Geoff euphoric. A star and US emblem on her lapel indicated that she was working in a civilian capacity for the US Army in the Pacific.

Inevitably, the two people who reunited in Australia in October 1945 were different from the newlyweds who had been separated almost four years previously.

As Geoff told me: ‘Both of us had changed; we’d had our own experiences. However, God is great and he enabled us to overcome all sorts of problems.’

One of the main obstacles was Louise’s resistance to her husband’s new calling. She had not intended to marry a priest and initially refused to countenance the idea, so Geoff returned to his role as an administrator in the Malayan Civil Service. Nevertheless, it eventually became clear to her that the man she loved was being compelled towards ministry by something beyond himself. The independence of Malaysia in 1957 hailed the end of an era, but provided a natural opportunity for Geoff to go forward for ordination.

Forgiving the Japanese

Along with having four children, the couple went on to share decades of ministry both in England and back in their beloved Malaysia. There were Japanese congregants in the church in which Geoff served as a mission partner. The irony was not lost on Geoff as, in this respect, his greatest spiritual battle came soon after his POW experience.

As he settled back into civilian life, Geoff still experienced a burning rage whenever he caught sight of the Japanese flag and its red sun. The brutal experiences had gouged deep wounds. A turning point came during a normal day in the district office. Geoff received a phone call from the Japanese consul. It was a cordial and inconsequential call, but emotionally it left Geoff in turmoil.

He recalled: ‘This sort of thing just could not go on, and from that day I prayed that God would change my attitude if I could not effect the change I sought myself.’

Things began to change and, in hindsight, Geoff viewed these first steps along the road to forgiveness as key to his being ready to offer himself for ministry in the Church.

Tracing the rainbow

When my grandfather published the account of his time as a POW, he titled it The Rainbow Through The Rain, a reference to a poignant line in the hymn ‘O Love That Will Not Let Me Go’:

O Joy that seekest me through pain,

I cannot close my heart to thee:

I trace the rainbow through the rain,

And feel the promise is not vain,

That morn shall tearless be.

(George Mattheson, 1842-1906)

I was glad to have been able to record my grandfather’s recollections with him. I had read his story, but hearing it in person brought home the extraordinary courage demanded of him and his generation.

It also helped me understand him as a person, especially his frugality, forged by a life in which no scrap could afford to be wasted. Yet hardship had not forged a hard man. Geoffrey Mowat was generous and gentle, with a deep spirituality and willing to see the good in anyone. By God’s grace, a rainbow emerged from even the darkest clouds.

Quotations are from The Rainbow Through The Rain (New Cherwell Press) by Geoffrey S. Mowat (1917–2008). To purchase a copy email albrierley@btinternet.com You can hear the radio documentary on Premier Christian Radio, Monday, 31st August at 10pm or at premierchristianradio.com/rainbowthroughtherain

Lulu’s war

Geoff and Louise met at Oxford University and married in 1940, having received a special dispensation to wed in advance of Geoff’s placement with the Malayan Colonial Service.

Louise was evacuated from Singapore in January 1942, and Geoff gave Louise his signet ring to wear until they met again. While Geoff was destined for captivity, Louise was borne in a different direction altogether. Her secretarial career took her to Brisbane, Australia, working in a civilian capacity as private secretary to General Marshall, deputy chief of staff under General MacArthur himself.

From this position, Louise had an unprecedented view of the war in the islands of the South West Pacific. After two-and-a-half years, MacArthur’s strategy was successful enough to warrant a move to the Philippines. Louise was required to go into uniform and was swiftly designated as a lieutenant in the Women’s Army Corp (WAC).

Louise was confident, intelligent and successful in her own right. Perhaps it was no surprise that she had misgivings about becoming a vicar’s wife following her reunion with Geoff. She described his call to ministry as ‘one of the greatest stumbling blocks in our married life’. But despite her initial resistance, she said that ‘God was able to take it away in time’ in what would become the ‘joint adventure of a lifetime’.