You’ve never participated in mob violence, have you? Neither have I. Whenever I read about it, I always wonder how on earth a normal human being could do such a thing. Spontaneous lynchings of black people in America’s Deep South. Smashing Jewish windows and beating Jewish shop owners (and, eventually, genocide) in 1930s Germany. Rwandan Hutus turning on Tutsie neighbours. There are more local examples too, of course: a bar-room brawl that ends with one man on the ground and ten men kicking him. A gang of children beating and eventually stabbing a boy they played with a year ago. Part of me wants to believe that the people involved are nothing like me. But it is just not true.

Many who join mobs that assault or kill are normal, even ‘good’ people. But as Christians, we know that no one is truly good. We all contain the seeds of sin. We are all, every one of us, potential members of the baying mob, the stabbing gang, the society supporting the victimisation of a minority.

This truth is evidenced throughout history. We know the evil of the Holocaust had its roots in the evil of racism, and we know that Hitler’s racist ideas were hugely popular in Germany. To say that all Germans were or are evil is to fall in to another racism. We know that after the Rwandan genocide, Hutu mobs fled into Congo, pursued by Tutsies, and both groups committed appalling acts of violence against each other and local Congolese. And we know that today’s perpetrator of gang violence or hooliganism might be tomorrow’s victim.

THE TWITCHFORK MOB

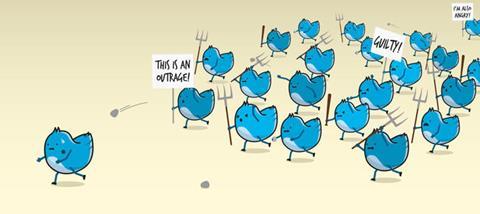

You see the same thing online. Ordinary people become part of baying mobs, propelled beyond the boundaries of what they would ever consider moral by the sensation of being in a crowd. Online, there is less danger of actual violence (though threats of violence are depressingly common), but the mentality is the same: an enemy or victim has been identified and we egg each other on to more intense, more creative, more extreme expressions of communal anger and hate. The hate itself takes on a life of its own.

MOST OF THE TIME, THESE OUTPOURINGS OF HATE ARE NOT REALLY ABOUT THE ISSUES AT ALL

Online, it’s sometimes called a ‘twitchfork mob’ – a combination of ‘Twitter’ and ‘pitchfork mob’ that captures the spirit of the frightening madness of crowds in an angry online world. An outrage is identified. Anger at the transgressor is stoked. Popular aggression grows like a snowball of rage until millions of people might be calling for the enemy’s sacking, death or violation. What makes it different from, say, a hate campaign against a public figure is that it tends to revolve around a single incident and inspires people who never had any prior dealings with the individual to focus white-hot anger at them (usually demanding that they be sacked). What makes it complicated is that quite often the initial reasons for the anger are perfectly sound.

ROUGH JUSTICE

Recently, for instance, the Internet boiled over with outrage at an American dentist who hunted and killed a lion named Cecil. You may have seen it. Enough people find the activity of killing animals for pleasure abhorrent that the ground was already fertile. Add to this some anti-American prejudice (for the worldwide audience), the fact that the lion had a name, and here was the perfect online storm. It lasted a week, but the effects on that dentist (who had to go into hiding following the furore) will be felt for years.

Or take Justine Sacco, who boarded a plane bound for South Africa while sending a satirical (if distasteful and easily interpreted as racist) tweet about white people not getting AIDS. Her Twitter account had only 170 followers, a pitifully low number in social media terms, and yet, by the time she landed, her name was part of the most popular topic trending on Twitter. She lost her job, future chances of employment and suffered appalling threats from thousands of people who publicly wished for her death. People who must, on a daily basis, usually behave decently and compassionately. People with jobs and families of their own.

Scientist Tim Hunt made a sexist joke at a conference and was broadly attacked by both commentators and the Twittersphere until he quit his honorary fellowship at University College London. And the list of online victims and perpetrators goes on…

IS SOCIAL MEDIA TO BLAME?

The power and cultural significance of twitchfork mobs and online lynchings are recent developments. They are only possible in a society like ours, with its ubiquitous broadband and constant access to (and obsession with) social media. But blaming the technology would be a mistake. The popularity of platforms such as Twitter have made these instant campaigns to shame and inflame possible, but it is human nature that makes them happen.

Are these shaming tsunamis of anger an entirely negative phenomena? Perhaps the object of hate deserves all the anger focused on them?

The Bible can help us answer these questions. It provides us with wonderful images of both the guilty and the innocent facing the anger of the mob.

THE GUILTY IN SCRIPTURE

An example of a guilty person facing the wrath of the crowd can be found in the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1-11).

Jesus tells the crowd of men who want her sin punished that only if they are without sin do they have the right to punish her. His message and example of grace in that moment are as eternally powerful as they are complicated to apply to our daily lives. Does

his reaction mean we should never distinguish between sin and righteousness? Clearly not. Does it mean that we should always allow wrongdoing to continue, in the name of mercy and grace? Unlikely. But Jesus’ attitude here, deliberately contrasted with that of the crowd by the Gospel writer, is one of consideration and calm. He is not carried away by the frenzy of righteous anger surrounding him. He takes his time. He scribbles in the dust. And, separated from the infectious enthusiasm for violence, he can see the value of mercy without having his judgement clouded by anger.

Disrespect for fallen soldiers, casual sexism or racism in a society overwhelmingly plagued by those forces and a wanton disregard for animal welfare rightly inspire anger. The key for Christians is whether we should allow our reactions to be dominated by those feelings, particularly when they are amplified by the sense of immediate belonging that a mob bestows on its members.

THE MOB BAYS FOR JESUS’ BLOOD

Nothing among the archetypes and iconography of human evil expresses this mass insanity better than the crowd baying for the blood of Jesus. Every schoolyard pile-on and childhood act of coordinated cruelty, every lynching, every swarm of decent people caught up in the madness of the mob is a pale reflection of the crowd crying ‘Crucify him!’ And we know it, when we read it, when we see it portrayed in passion plays and on film, to be wrong. It is a sin that every one of us could easily commit, but sin nonetheless.

Whether it is a reaction to a genuine wrong or an overreaction to something innocuous, Jesus’ own reaction to mob hate (and his own victimisation by it) show us that we, as Christians, should not participate.

‘But, what if the thing that was said or done was really bad?’ I hear you ask. Well…Is adultery not bad? Is the blasphemy Jesus was accused of not appalling, if it were true?

One of the problems with today’s spontaneous online hate campaigns is the speed at which they move. How likely is it, in our desire not to be left out or behind, that we will examine all the facts? How likely is it that facts would be available at all? Without time for fact checking, understanding context and sober reflection, and with the immense peer pressure of thousands (sometimes millions) of people all holding the same strong opinion, how likely are we to dissent from the crowd? How many of us are strong enough to stand up against a crazy storm of crowd-sourced bullying?

Because bullying is what it is. We might think it’s deserved. We might hate the person being bullied for what they have done. But when the ratio is 1,000 or more people threatening a lone individual they have never met, it’s safe to say that it is bullying.

Of course, you could say that what is happening in these situations is justice. Rough justice, to be sure, but essentially people reaping what they sow, like breakers of the Law in the Old Testament, endangering the life and shalom with God of their whole community. In such situations, is it not a positive thing that organic, spontaneous movements of people rise swiftly to dole out discipline?

Perhaps. But a few factors should give us pause.

THE ISSUE BEHIND THE ISSUE

Most of the time, these outpourings of hate are not really about the issues at all. They are about finding someone who has broken a rule or offended our beliefs – and our desire to see them punished. I know there is a debate to be had among Christians about how grace and justice must fit together in a righteous society, but I cannot reconcile love with pleasure or joy at someone else’s punishment. Not the love Jesus asks of us.

ARE THESE SHAMING TSUNAMIS OF ANGER ENTIRELY NEGATIVE?

And if we want to argue that we are acting in love, like a parent doling out discipline, we should probably check our attitudes for pettiness and hypocrisy, just to be safe.

If you are very angry about a stupid picture at a military graveyard but not particularly angry about soldiers being sent to die in wars, you may have some thinking to do. If you think one ill-judged joke should define a Nobel Prize winner’s career or destroy that of a woman who has done you no harm, I believe you need some perspective. If you cannot tell that something is a joke or think the world would be better without satire or public joking, you’re unlikely to be a great witness to God’s joy. And if you can’t bear to live in a world where opinions you disagree with go unpunished, you may be part of the problem.

Should these issues be discussed? Yes. Should sexism, racism, callousness and disrespect simply go unchecked, and should all jokes be accepted without question? Of course not. But the choices available to us are not limited to saying nothing or destroying someone’s life for one verbal offence. As Christians, when we are faced with a baying mob asking us to join in, I think it’s best, regardless of the alleged sin being punished, for us to take Jesus’ lead and let he or she who is without sin tweet the first stone.

5 (of 10) commandments for social media

1. Thou shalt not fight for Jesus

Aggressive argument bent on winning and humiliating the opponent rather than bringing them over to your side is so unappealing. And while we’re not called to be appealing, we are called to make disciples. Most aggressive online religious arguments result in neither side changing view.

2. Honour your friends and family

Nobody wants to be tagged in a picture that is unflattering. Nobody wants the photo posted in which they look terrible but you look awesome. Don’t be that guy. Do unto others…

3. Thou shalt not say cryptically dramatic things to get attention

Please stop posting things like ‘I guess there’s no point even trying’ and ‘Never push a forgiving person too far. Eventually they will get tired of being a doormat and you will realise what you’ve lost’. We get it. Everyone is awful. You are nice. But if you have to say it (but can’t bring yourself to do so directly), remember that someone out there may be writing passive aggressive statuses about you.

4. Thou shalt not put ‘clever’ above ‘helpful’

We’re about due for another ice bucket challenge or ‘turn your profile pic into your favourite dog on children’s TV in the 80s to raise awareness of dog-fighting in Ukraine’ type of popular social media movement. Don’t like the new craze? Don’t participate. Think there’s a better way to do it? Well, then model it and make it popular, smart guy.

5. Thou shalt not post pictures of your coffee

It literally comes out of a machine. And before that, it was in a bag. Every barista in the world can make that leaf pattern in the foam, so please believe me when I say there is absolutely nothing special about your coffee.

Read Jonty’s remaining five commandments on our blog.

The internet shaming of Lindsey Stone

Lindsey Stone was a carer working with disabled girls when, four years ago, a friend posted on Facebook a joke picture of her standing in front of a sign at a military cemetery that asked for silence and respect. In the picture she

is seen comically shouting and making an offensive hand gesture.

Lindsey hadn’t set up privacy settings on her Facebook page, and to her surprise the photo went viral. ‘Lindsey Stone hates the military and hates soldiers who have died in foreign wars’, ‘You should rot in hell’ and ‘Just pure Evil’, were some of the comments she began to read about herself.

Death and rape threats followed, and a ‘fire Lindsey Stone’ Facebook page was soon created, attracting 12,000 likes. Lindsey lost her job, and spent the following year almost entirely at home, struggling with depression and insomnia. She has since attempted to rebuild her online ‘identity’ via a professional agency.