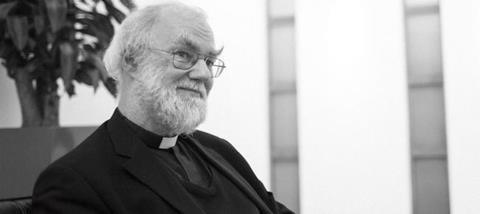

Rowan Williams looks like someone who’s had a weight lifted from his shoulders. When I tell him that he seems to be a relaxed man today, he jokes back, ‘I can’t imagine why.’

But we both know why. For over ten years, Williams has led the Church of England as the Archbishop of Canterbury during one of the most turbulent decades in its 500-year history. Controversy over gay priests and women bishops has dominated the media, while the pressures of declining church attendance continued to grow. As he hands the role on to Justin Welby, the phrase ‘poisoned chalice’ comes to mind, though Williams is confident that his successor is the best person to confront the challenges that remain. ‘I’m so excited by his appointment. Genuinely. He’s a focused, clear and very impressive thinker.’

The same thing could be said of Williams, who was perhaps the most academically gifted Archbishop yet. He began by teaching theology in Cambridge, where he met his theologian wife, Jane (they now have two children), and went on to become an Oxford professor. Several years as Bishop of Wales preceded his time as Archbishop of Canterbury, and now he is returning to academia to become Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge. Reinvigorating the Church of England’s outreach meant encouraging an intellectually credible faith, and was one of his main aims as Archbishop from the outset.

In person, the former Archbishop seems unassuming, almost to the point of being shy. He’s softly spoken and seems to weigh every word ? his measured thoughts conveying the sense that a lifetime’s learning and reflection are being drawn upon.

More than one wag has likened him to Dumbledore from the Harry Potter films. His trademark beard and curly eyebrows certainly look the part. But unlike his fictional counterpart, there is no magic wand he can wave to unite an increasingly fractured Anglican Communion. On that front, he describes his own success as ‘limited’, and that the recent defeat of the vote on women bishops left him with ‘a deep sense of sadness’. He describes frankly how those Church struggles have affected his own spirit as ‘banging my head against a brick wall in prayer’

But don’t let the gentleness and humility fool you. Rowan Williams is still passionate about the Church. To those who feel beleaguered by an increasingly secular society he says, ‘Christianity has nothing to fear. We have the promises of God, you know. Basic as that.’ And to liberals within the Church who question the divinity of Christ, he responds, ‘Does it matter? Well, actually, it does, rather.’

During our conversation, I discover that Williams thought about joining the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox Church early in his Christian life. But he eventually decided to stay put in the Church of England, despite it being ‘continually exasperating’. Why? In a way, his explanation seems to sum up his last ten years. ‘Don’t go looking for a perfect church ? the one that you’d invent if you had the choice. Just inhabit the place where God has put you.’

Growing up in Wales, was faith always part of your life?

Yes, we were a Welsh non-conformist family. When we moved to Swansea we became members of the Anglican Church there. It had a tremendous amount going on, and constantly gave you the impression that Christianity made you live in a bigger world, rather than a smaller one.

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t involved in the life of the church and conscious of having a faith. I often think of two events that really brought it home to me. One was when the curate took me along to a Russian Orthodox liturgy. I was completely overwhelmed by the experience of beauty, worship, mystery and excitement in that. The sense that you were on the edge of something enormous.

And then I went to hear Richard Wurmbrand speaking about his experiences as a prisoner in Romania. Again, suddenly something came through to me of the seriousness of the claims of Christ. I think of those two moments, especially in my teens, as having been decisive.

Did you ever think about joining the Orthodox Church?

Occasionally, but I couldn’t quite cope with the idea that you had to uproot yourself culturally. I thought quite a bit about becoming a Roman Catholic at one point, partly because I was thinking a lot about being a monk in my early 20s, but I seemed to be brought back again and again to the fact that ‘this is where God put you’. Don’t go looking for a perfect church ? the one that you’d invent if you had the choice. Just inhabit the place where God has put you.

Did you ever consider any other career?

As a student I used to help run adventure playground schemes in south London and I did a bit of work with the homeless in Cambridge. I did think at one point about social work as a future, but I think I recognised that would be saying ‘no’ to quite a bit of what energised me.

And social work is a big part of Church ministry, anyway...

Yes, and God gave me a nudge on that on my second day in Cambridge as a student, meeting a homeless person on the street and ending up spending a couple of hours with this man. It was as if God was saying, ‘Look, here you are in this privileged place where you’re going to have a great time studying. Just don’t forget the shadow side of it all.’

You met Jane while teaching in Cambridge. Was it love at first sight across a lecture theatre?

Yes [laughs], our eyes meeting across a crowded seminar room. It’s very romantic. We met at seminars quite regularly and went for tea afterwards, and the rest is history. Jane was at that time working on her research in modern German theology. I had some interests in that area and increasingly discovered we had a lot of other things in common.

You went on to become Bishop of Wales ? was that a big change to the academic setting?

Somebody asked me not long after I had moved back to Wales whether I missed the teaching. And I said, ‘Well, I’m still teaching, it’s just a different mode.’ The challenge of how you make sense of things to a confirmation group in Abertillery ? that’s as much of an intellectual challenge as a seminar group in Oxbridge. For all the struggles and difficulties that being a bishop brings, it was a very, very happy time.

What were your hopes and dreams for the Anglican Church when you became Archbishop of Canterbury in 2002?

Two things were at the top of my list. One was doing something about general theological literacy ? promoting the idea of a Church that took thinking seriously ? partly because I experienced theology as something enriching, not threatening or undermining.

The second thing was encountering the first green shoots of new congregations springing up, and people who were pushing the boat out in terms of new styles of Christian life. So within two years we were launching the Fresh Expressions movement in the Church of England, because it seemed to be the moment when God was dropping heavy hints that this was what we should do.

A decade on, have you hopes been fulfilled?

I think so, yes. My hopes and prayers have been richly met there. In terms of numbers, they don’t always show up on the statistics, but we know that probably the equivalent of a whole worshipping diocese has been added to the Church of England.

What has been the greatest challenge during your time?

No surprises there, really ? just the different ends of the Communion drifting further apart, and the extreme difficulty of getting people round the table to keep them talking.

Specifically on homosexuality?

I’d always seen it as the role of an Archbishop just to try to keep people at the table. The difficulty is that a lot of people think that the role of an Archbishop is to ‘solve it’ with pronouncements ? ‘That’s enough from you lot, we’re going this way.’

Do you feel that you did keep people at the table?

Limited success, I’d say, limited success. It was obviously painful that a lot of people decided that they couldn’t come to the Lambeth Conference. Even so, a lot did come and we discovered a new way of doing business there which helped some of the people from the smaller churches feel they had a role.

In my time, I tried to give a little bit of priority to some of those churches which were a bit off the centre and to minority churches under pressure. So the visits that really made an impact to me were to Melanesia, the Solomon Islands, to Sudan, a church that is under tremendous pressure. More recently, Congo ? a heartbreaking place to be, a tiny Anglican Church doing disproportionately large things. Those are the places that really stick.

How did you feel when the vote on women bishops was defeated last year?

I felt a deep sense of sadness, feeling that we were in danger of losing a generation of very able women clergy who would probably now not make it in time, and feeling that all of us (me included) had just not managed it well, somehow. It wasn’t communicating the gospel by the way we had done our business. It was that feeling that we were certainly hung out to dry in the eyes of the world.

It provoked strong reactions, even from those outside the Church.

It’s fascinating that in spite of what people say about the secularisation of the country, so many surprising people still have ‘an investment’ in the Church. They still want the Church to look serious, and are worried that it doesn’t. Clearly the Church can’t govern itself by opinion polls or the reaction of unbelievers. At the same time, you have to ask (and I think there’s a good New Testament principle), ‘What does it look like, what does it sound like?’

I imagine there were plenty of times over the years that you were frustrated by the way the media reported your words.

[Laughs] Oh, one or two! It’s like the weather ? you can’t get away from it. You sort of live with it and look for the least stupid way of responding. It’s no good whinging ? that’s how it is. We are in a particular kind of media culture; the 24-hour news cycle is a very voracious eater, it just wants food all the time, and it wants conflict and drama. It’s not always what’s actually happening.

What advice would you give your successor Justin Welby?

I would underline the absolute importance of keeping in touch with the front line, with the parishes, with the schools. Find what nourishes you and make room for it.

What strengths do you think he will bring to the position?

Loads! I’m so excited by his appointment. Genuinely. He’s got the international experience that he brings to bear from time in Nigeria, and of course all that expertise and sophistication in the financial field, as well as a real, direct, lucid theological conviction. He’s a focused, clear and very impressive thinker.

You’ve debated Richard Dawkins, a vocal atheist. Does Christendom have anything to fear from secularism?

Christianity has nothing to fear. I do take that absolutely seriously as a fundamental biblical principle. One of the first things that Jesus says to the apostles is ‘don’t be afraid’, so let’s not cast it in terms of what Christianity has to fear. We have the promises of God, you know. Basic as that.

Have we reason to be grumpy and anxious?

[Laughs] Well, sometimes, yes. And what’s the future? Can we be confident that the Church will be respected, influential, taken seriously? Well, no, actually; there’s no guarantee of that in the Bible or anywhere else.

As for explicit attacks on the Christian faith by some intellectuals ? last summer I picked up a book in a shop in Edinburgh which was a Christian response to attacks on the faith from anthropologists, physicists and biologists, written in 1932. I read it and thought ‘This is exactly what we’ve been hearing, and there really aren’t any new arguments here.’ So I don’t lose too much sleep over that.

Are people less open to faith than they once were?

I don’t feel people are more hostile to faith that they were 40 years ago. In fact, there are times when I’ve felt people are less hostile. But we’re living in a culture where commitment is not fashionable or easy. That’s not just about churches ? it’s about political parties, the readership of the daily paper, and it’s about relationships, too, sometimes.

So rather than simply thinking ‘We are having a bad time,’ we ought to be asking, ‘Exactly what is it about the culture we live in that is so short term, so commitment-phobic, so reluctant to be part of a community?’

Are there any particular strands of theology today that give you cause for concern?

It’s the theologies that veer off at one end or the other that worry me; the ones that say ‘Well, actually, does it really matter that much if we talk about God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit? Does it matter that Jesus is unique?’ And I think, ‘Well, actually, it does, rather.’ This is the whole shape of life and prayer and hope that’s being defined here. So I do get worried by some kinds of liberal theology that deny the divinity of Christ, that seem to suggest that pretty well anything goes.

That try to paint everything as metaphor?

Yes. There’s tough, truthful reality here that we’ve got to have our noses rubbed in.

And on the other end?

On the other end, is people saying, ‘Well, in addition to all that, I’m going to tell you 16 extra things you’ve got to believe in order to qualify as a real Christian.’ Let’s say, the way in which salvation operates, which I know is quite a controversial subject. The language of penal substitution ? the atonement ? that Christ bears our punishment for us, is part of a spectrum in the New Testament. A very important part, and I’m not wanting to deny it. But is that the only way that redemption is spoken of in the New Testament? Of course it isn’t. What’s going on in the cross and the resurrection is so colossal that there’s no one theory that’s going to get all of it in.

You wouldn’t give penal substitution precedence over any other way of looking at the cross?

I don’t think so. I think it’s a rather curiously modern way of coming at it. It’s not somebody trading with the Father for favourable conditions. Goodness knows it’s a complicated thing, and I remember when I was talking about it to my own daughter before her confirmation this was the most difficult thing we got in to.

In your time as Archbishop of Canterbury, did you have doubts about God?

Doubts that God exists? Doubts that God is loving? I don’t think so. Doubts about whether I’m making any sense of God? Yes, very regularly. And a bit of the sense of sometimes banging my head against a brick wall in prayer, and saying, ‘I just do not know what is going on.’ A lot of that, a lot of that.

But I think that’s why it matters so much for me to say that the promises of God are where we start and finish, not how it feels or looks for me or for society at any one moment.

When you hit those banging your head against a brick wall times ? where did you draw spiritual and mental strength from?

I suppose it’s a mixture of things. One is the sheer fact of feeling committed to doing it every day. Just get up and pray, get up and sit there, kneel there, and say, ‘Here I am.’

As a priest I’m obliged to say morning and evening prayer every day, and I’m obliged by personal resolve to spend a certain amount of time every day in silent prayer. And you just do it. No argument. Disciplined rhythm does uphold you, and I think it’s a great blessing that we have got the daily offices of morning and evening prayer.

Because you can’t always come up with the words yourself?

It’s like swinging from ring to ring in the gym ? you propel yourself forward and grab hold of the next one and keep moving. Not that I’m a great aficionado of gyms [Laughs].

Then there is the unexpected way in which in worship, in some great celebration or some quiet event in a parish church, you feel ‘something’s happening’. I don’t know what it is, I don’t know what I’ve got to do with it, but something’s happening.

The presence of God in some way?

Yes. A God who acts. A God who has promised to turn up. The other thing that keeps me going is the examples of other people’s faith.

Any individuals you are thinking of?

There are lots of obvious heroes, but I’m thinking more of the people I meet face to face. I’m thinking back to a youngish mother I was with a couple of years ago in a hospice who died not long afterwards. Just listening to her expression of faith and her expression of concern for her children ? it’s those things that come back when you say, ‘It makes sense for them.’ I’m just kind of paddling along hopefully, but somewhere it’s making sense. And if it makes sense in circumstances like that, it makes sense. Period.