News that the CofE hopes to create a £1bn fund to address the legacy of slavery has been met with mixed reactions. It’s another indication that there’s still a long way to go to eliminate racial discrimination, says Guy Hewitt

As someone with multiple heritages - African, Asian and a smattering of English - the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination which we celebrate on March 21, resonates deeply.

The distinction between racial prejudice (biases between groups) and racism (systematised by one group’s social influence, legal authority and economic and political power) is a lived experience.

Notwithstanding recent reassuring events, such as the Church of England’s £1bn target to address historical links to the slave trade, we remain some way from being united in Christ. Only 15 of the 350 leadership posts in the CofE are held by people from a minority ethnic background.

Racial justice is still not fully embedded in the Church’s mission.

People are tentative to engage in racial justice for many reasons: the highly contested and polarised debates dominated by a vocal, dissenting minority; a zero-sum mindset concerned with perceived loss; shame or ignorance of an oppressive and exploitative colonial history; fragility and vulnerability due to racial illiteracy or challenging discourses; and a theological misunderstanding that overlooks that knowing God is to do justice (Jeremiah 22:16).

A perceived reality

For many, perception defines reality, which causes us to misconstrue others’ situations. Consider the hymn ‘All things bright and beautiful’, specifically the oft-omitted verse: “The rich man in his castle / The poor man at his gate / He made them, high or lowly / And ordered their estate.”

The hymn writer was the wife of an Archbishop. She lived in Ireland at the height of the potato famine. Yet with millions dying of starvation all around her, and the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19) to guide her, she nevertheless concluded that God had “ordered their estate”.

In this journey towards becoming one in Christ, all are needed and all must be included

Perception defining reality is an important consideration in understanding how the predominantly white, male, middle-class norms of our Church impact on how we perceive justice issues.

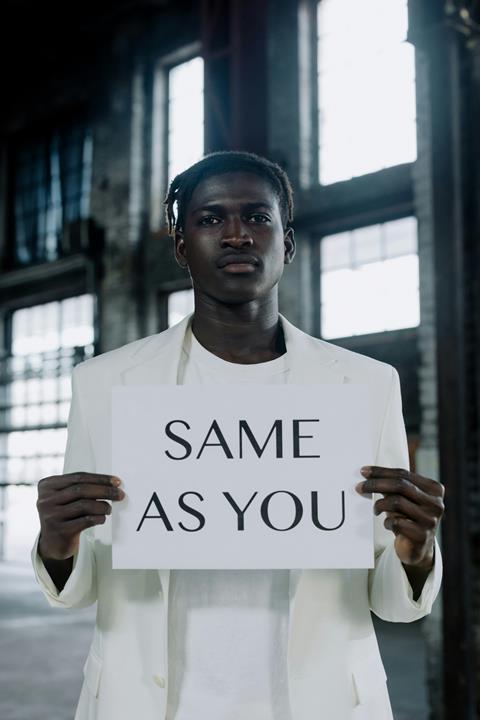

The Church’s commitment to racial justice is a stand against the pernicious sin of racism. Racism is idolatry; it denies the image of God in all persons (Genesis 1:27). Destructive and dehumanising to its victims, racism also perverts those who benefit from its lie. “The abomination of transatlantic chattel slavery” was, as Most Rev Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, put it “blasphemy”.

Antiracism is rooted in Jesus’ commandments to love our neighbour as ourselves (Matthew 22:39). Our Lord defines a neighbour as someone who, at great risk or sacrifice, embraces the ‘other’ regardless of identity (see Luke 10:25-37). The imperative to “go and do likewise” (v39) demands that we embrace everyone as equal members of the community of Christ. Loving those who are marginalised is how we perceive Christ in the world.

Not neutral

When I ask the question: “How has race shaped your life?”, most of my white English friends struggle to answer. Yet for those of us who are not white, it is an ever-present reality.

Many people seek solace in being ‘nonracist’, asserting that they “don’t see colour” and reassured by racially diverse relationships. However, in a racialised society, it is simply not enough. We must become antiracist.

As Desmond Tutu said: “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

Racism is idolatry; it denies the image of God in all persons

To be antiracist is a radical choice in the face of history and prevailing preconceptions. It requires a conscious reorientation of one’s sense of self. Being antiracist is believing that racism is everyone’s problem, that we all have a role in stopping it.

In this journey towards becoming one in Christ, all are needed and all must be included; there mustn’t be any losers.

If the Church is to advance on racial justice, we need each and every member to be committed to this journey of oneness in Christ. Most importantly, we need our English brothers, sisters and leaders to recognise that, while racism harms Black, brown and other minoritised groups disproportionately, it was historically systematised by Europeans, remains rooted in their power and, as such, can only be dismantled through their direct engagement.

Confronting the reality of racism is challenging. It involves self-examination, uncomfortable discussions and acknowledging ugly truths, both historical and contemporary.

No comments yet