The effects of slavery are still keenly felt by Black Christians in the UK today. Only Jesus can ultimately heal those wounds, says Richard Reddie

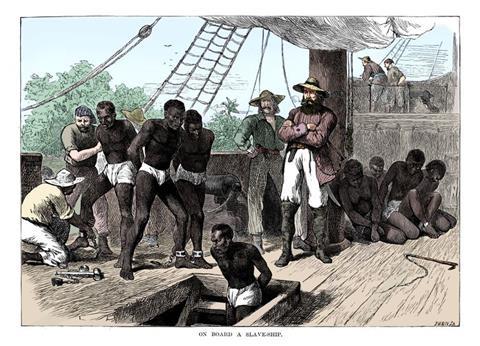

The Transatlantic Slave Trade (TST) and the chattel enslavement of African people from the 15th to the 19th Century is undoubtedly one of the grimmest episodes in human history. The TST remains the largest forced migration ever; between 11-15 million people were coercively taken from Africa to toil in the Americas. African enslavement in the West, especially the USA, was described as the ‘Original sin’ as it saw human beings, who were made in the image of God, treated like animals (and in some instances classified as such). While enslaved Africans worked and died on plantations, farms and estates, the products of their labours enriched Europe, particularly Britain, economically, socially and culturally.

Jesus Christ has the capacity to free both the body and mind

The TST advanced the belief that those with darker skins were morally, intellectually and spiritually inferior to their white counterparts, and more suited to slavery than freedom. In the 18th and 19th Centuries, European scholars developed ‘racial science’ that advanced theories such as Black brains being smaller than White ones. I would argue that the lasting damage caused by the TST and African enslavement has been the way that Black or African people are regarded and treated, including widespread Afriphobia. This legacy also includes the way Black people see themselves, which can manifest itself in an internalisation of certain widespread racialised stereotypes to the point where they become pathological.

Rewriting the Bible

European missionaries used the Bible as part of a dehumanising and brainwashing process to justify not only Black enslavement, but Black inferiority. Tragically, Bible verses were distorted to show how Christianity condoned African enslavement, and that true freedom could only be obtained in heaven, after death. Indeed, missionaries sent to what was then the West Indies produced a redacted version of the Bible that excluded Exodus and references to freedom or condemnation of slavery. This Bible, alongside other ideas and practices, was foisted on enslaved Africans to make them accepting of their appalling treatment.

However, history also reveals that these fiendish attempts ultimately failed. Consequently, the legacy of Black people in the Diaspora has been one of resistance, sometimes active, at other times, passive - against their ongoing dehumanisation. Equally, this resistance often used the very same ‘slave master’s Bible’ as the source of inspiration to fight for freedom.

Deep roots

But while the chains are gone, to quote Bob Marley, “we are still not free”. The racism which took root during the TST is the lasting legacy of that system, which manifests itself today in so many ways. The Black Lives Matter movement can be traced directly to African enslavement, when Black lives were cheap and disposable. We still live in a world were myriads of Black people, especially in Africa, constantly die from war, famine, drought and other natural disasters, yet this is often not considered news. Juxtapose this with coverage of any shooting in a mid-Western US school, shopping centre or religious institution, and one sees the obvious discrepancies regarding the value of human life. (This comparison can also be applied to refugees fleeing danger in parts of Africa and Asia, as opposed to Europe.)

Missionaries used the Bible as part of a dehumanising and brainwashing process

When the world focuses on Africa and/or its Diaspora, the news is invariably negative. International aid agencies, including Christian ones, present Africans without agency; they are people totally dependent on White assistance. Their campaigns portray pitiful-looking, fly-infested children with distended stomachs and outstretched arms, waiting to receive help from European-based aid agencies. What is unhelpful is that this dehumanising approach is also used by animal sanctuaries when they solicit funding for their work to help imperilled animals.

This appalling legacy also sees Black professionals confessing (in their candid moments) about how their competency and intellectual capacity are constantly being questioned. To be Black, gifted and professional is still something of an oxymoron in our racist society, evidenced by the dearth of such individuals in the boardrooms of FTSE 100 companies or in senior positions within our larger, historic churches.

Negative connotations

In short, ‘Black’ is a pejorative term with a plethora of negative connotations, borne out even in dictionary definitions which reinforce the notion. Black is not deemed beautiful in the West, where the epitome of aesthetic magnificence is blonde hair, blue eyes and pale skin. It should come as no surprise that Jesus and his angels are portrayed like this in Christianity and popular culture, while the devil and his minions are the diametric opposite.

Equally, Africa is regarded as the ‘dark continent’; savage, untameable and wild. I am a fan of wildlife documentaries, and all of them use such language and imagery when describing the natural world of that continent. Moreover, its people - thanks to Hollywood and other unsympathetic cinematic portrayals such as Tarzan - are a human version of this. And the British term, “going native”, first coined during the missionary era, is also meant to reflect the damage the continent can inflict on its inhabitants. This is despite the fact that Africa, notwithstanding the geopolitical shenanigans and economic exploitation of the West, is on the cusp of game changing industrialisation. From a religious perspective, Christianity is growing faster in Africa than anywhere else in the world!

If you are constantly told a negative narrative about what it means to be Black, this can have a detrimental impact on the individual and collective psyche. One Black academic described this as “post traumatic slavery syndrome”, which, among other issues, can see Black people disfigure themselves via plastic surgery and skin lightening creams to look whiter. The late Michael Jackson was a tragic example. Black people often talk about “good hair” (curly hair that is loose and wavy) and “bad hair” (that must be ‘tamed’ via straightening). For others, the idea of being associated with anything Black, whether a business, doctor, lawyer, community project or church, is something to be avoided. Many Black churches, and Black Christian homes, still have images of a white Jesus on their walls!

Healing the scars

So what does it mean to be Black and Christian today? Marcus Garvey called upon Black people to “emancipate themselves from mental slavery” as “none but us can free our minds.”

As a Christian, I believe that Jesus Christ has the capacity to free both the body and mind, and so the forthcoming webinar, ‘Setting us free: How to repair the damage of four hundred years of slavery to Black Christians’ is a fantastic opportunity to hear what God has to say on this matter. It is also an occasion for all Christians to unpack issues which, although they have their roots in the past, still continue to inform our world today. We will explore how we can use the power of God’s word to heal the damage caused by the TST so that we are all set free!

The ‘Setting us free: How to repair the damage of four hundred years of slavery to Black Christians’ webinar will explore how to heal the 400 years of damage caused by enslavement and racism to Black Christians. Book your free ticket here.