Do you like scary movies?’ It’s the question that can predict whether your relationship will last, according to the founder of one of the world’s most popular dating sites. In analysing ten years of data from millions of users, Christian Rudder, founder of OkCupid, discovered that of all the couples who have stayed together long term having met on his site, about three-quarters answered that question the same way. Both either answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’, but they agreed. Statistically, he says, that answer has a similar predictive power to whether couples believe in God.

‘Do you like scary movies?’ is also a classic line from the cleverest horror film of the 90s (more on that later) and a question that tends to make some Christians a little uncomfortable. Instinctively, many of us want to answer ‘No’ – regardless of whether our partners agree. It feels like our duty to have nothing to do with such things. For the more conservative, horror films are things of spiritual darkness, with the potential to open us up to demonic influences or at least to have a negative influence on us spiritually. If we feel we are too sophisticated and clever for such reasoning, we may still avoid horror films on the basis that they are stupid, exploitative and not good for society.

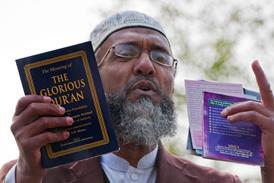

Which is a pity, really, since, according to Baptist minister, film buff and presenter of The Flicks That Church Forgot podcast, Peter Laws, ‘Horror is the only genre to really take the supernatural seriously.’ And surely Christians could do with all the help we can get in communicating the reality and importance of spiritual, supernatural things?

Is Laws right? Or are horror films really all just dangerous, demonic or dumb? With Christian-themed exorcism film The Vatican Tapes about to be released in the US and ‘Christian horror film’ The Remaining now available on DVD, perhaps it’s time we took another look at the genre that refuses to stay dead.

Demonic

At this point I should admit, I do like horror movies (and before you ask, my wife can’t stand them and we’ve been happily married for about as long as OkCupid has existed). I like them, and I think I always have.

As a youngster, I found Dracula unbelievably exciting, and ghost movies as terrifying and fun as any rollercoaster. I never related to the The Hardy Boys or GI Joe, but I devoured anything with vampires, werewolves or zombies in it. As a newly converted Christian in my early 20s, struggling with doubt and spiritual attacks on my faith, I remember watching Event Horizon, a horror/sci-fi crossover with a storyline involving demonic forces. It was terrifying. I walked out of it believing strongly that the devil was real and that he hated me, and that I never wanted to be without the protection of God in Jesus Christ. That horror film was an important instrument in the securing of my faith.

Horror films can be great art, and Christians should never be afraid to engage with great art

So, as far as I can discern, horror movies have been the opposite of a portal to the demonic in my life. But I can understand why they worry some people. These are films that often deal with dark, ugly spiritual matters. They are frightening. But then, the same could be said about films like Hotel Rwanda or Schindler’s List. As Christians we are called to think on ‘whatever is pure…[and] lovely’ but we are also called to think on ‘whatever is true…[and] honest’ (Philippians 4:8). We are neither promised nor required to live a life free from thinking of ugly or terrible things. Were that the case, much of the content of the Bible itself would be out of bounds.

Scott Derrickson, a film director (responsible for the wonderfully Christian The Exorcism of Emily Rose and the wonderfully scary Sinister), and himself a Christian, put it this way in an interview with Christianity Today in 2005: ‘In my opinion, the horror genre is a perfect genre for Christians to be involved with…[It’s] not about making you feel good, it is about making you face your fears. And in my experience, that’s something that a lot of Christians don’t want to do.’ Derrickson is that phenomenon Jesus-loving culture enthusiasts hope and wish for: a believing Christian working at an influential level in Hollywood. But because he works in horror, a genre that reaches far more secular audiences than the new wave of biblical epics, you have probably never heard of him.

You’ve probably never heard of filmmaker brothers Chad and Carey Hayes either. They’re also Christians and they wrote epically scary The Conjuring, a film that gives more space than you’d expect from a mainstream movie to the power of Jesus’ name in opposing the forces of evil.

In praise of The Exorcist

What is your perception of The Exorcist? So many Christians I meet have an automatic dislike for the film and even perceive it as evil. Yet this is a film which pits self-sacrificing, brave yet realistically flawed priests against not only the powers of hell, but the ignorance and incredulity of a materialist world that has forgotten the reality of the spiritual dimension. What more could any evangelical ask for from Hollywood? And yet for years fundamentalists have spoken against a film whose central scene demonstrates that it is only the power of Christ that can compel an unclean spirit to leave. This must be particularly annoying for William Peter Blatty, who wrote The Exorcist. He is a committed and active Catholic who was one of only a few filmmakers to defend Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ when critics began to attack it.

Horror films that deal with the deliverance from or exorcism of malignant spirits in particular have a long tradition of proclaiming openly that Jesus doesn’t just want us to work at our local food bank, but that we are in the midst of a spiritual war. These films are the perfect vehicle for engaging non-Christians with spiritual realities. But not all horror films dealing with the devil present a helpful message.

Christians should be concerned about and educate against films that present demons as sympathetic, or cool, or make Satan out to be mischievous or harmless, rather than destructive, hateful and dangerous. But, then, you don’t need to look to horror to find such unhelpful ideas. There is a reason, after all, that we are warned that Satan masquerades as an angel of light. His aim is for humanity not to take him seriously. So, when I think of films that could desensitise people to the dangers of evil and the occult, I think not of horror films that make us fear what the devil might do. I think of comedies and cartoons, jokes about hell. I think of the Liz Hurley film Bedazzled, or the Adam Sandler vehicle Little Nicky.

Dumb

Both those films are monumentally bad and really quite stupid, and it has to be said that horror is not immune, as a genre, to stupidity. The relatively low production values needed to provide scares (and, it must be said, the high tolerance for silliness among the horror-watching public) mean that there are many truly terrible horror films out there. So, if your objection to horror is that God calls us to excellence, to take art seriously and not to waste our time on uncreative chaff, you have a point when it comes to a huge proportion of horror flicks. And a huge proportion of thrillers, action movies, comedies and, let’s face it, family friendly films, too. Horror is not alone in this. But horror has also produced some truly great films.

we are in the midst of a spiritual war

The Exorcist won two Oscars and was nominated in eight categories. It won four Golden Globes, including best picture and best director. It’s well known film critic Mark Kermode’s favourite film. It’s a masterpiece of modern cinema. Hitchcock’s Psycho, Kubrick’s The Shining and Ridley Scott’s Alien are popular, brilliant and horror. Scream, the 90s film that both deconstructed and revelled in the slasher movie genre (and which made ‘Do you like scary movies?’ a creepy catchphrase for a while), was easily one of the smartest of its time, and The Ring and The Grudge were such good movies they became classics of both Japanese and Hollywood cinema.

Recently, Jennifer Kent’s masterpiece, The Babadook, with its subtle allegory of depression and parental neglect, proved that the age of horror films being great films is not over. It won the New York Film Critics Circle Award and the Australian Academy Award for best film (if you watch one horror film this year, make it The Babadook – it’s no exaggeration to call it both scary and beautiful.)

Horror films can be great art, and Christians should never be afraid to engage with great art, even if it is to critique it.

Dangerous?

However, most Christians’ objections to horror are not based on artistic merit. Most centre on whether watching horror is bad for you. I maintain that as with any genre of film, it is not what you are watching, but how and why you are watching – the motivations of the mind and the attitudes of the heart – that make the difference. Some types of horror film are more open to being watched badly than others.

We’ve touched on exorcism films, but what about the classics? Vampires, werewolves, and monsters are, I think we can all agree, not real. So watching films about them is about as dangerous as watching family films about Bigfoot. Or fairies. Both of which, incidentally, have had quite good horror movies made about them.

Ghost and haunting movies are, of course, theologically tricky, as my reading of the Bible doesn’t really make room for ghosts, but then, the Bible doesn’t feature many Spidermen or aliens, either. And even more than the superhero genre, haunting movies tend to have an essentially moral core that drives them. They are about righting a wrong that has lain uncovered for too long: a dark genre concerned with bringing secrets into the light. The Haunting in Connecticut is a recent example that is possibly too preachy and moralising, while films such as The Others and the 2011 British film The Awakening are subtle and beautiful in their treatment of larger societal wrongs.

Disturbing

Less moral are two genres I find problematic: slasher movies and a genre disturbingly known as ‘torture porn’. Slasher flicks focus on homicidal maniacs, who inevitably stab and slash their victims in spectacularly gory ways. These can be done well and responsibly, it is true, but the focus on violence, and the too-common linking of it with sexual titillation (which reached a low point in the 1980s) can, in my opinion, be polluting and send unhelpful messages about sex.

With these films it is not, as in other horror genres, the tension or fear that excites, but watching a human being suffer and die. I may be ignoring the most obvious thing to keep in mind about horror films – that they are works of fiction and fantasy – but I find that particular fantasy unhealthy.

Torture porn, made famous and popular by the Saw franchise, now just a parody of itself, is even more problematic. It takes what is unhealthy in the slasher genre and amplifies it, and distilling it to its most repugnant essence. Watching these films, which centre around hapless victims, psychologically and physically tortured by sadists, is the voyeurism of suffering, indulging in misery as sport.

Is it sinful to watch these films? I personally don’t think so. They are fictional, no one is truly hurt in making them, and the occasionally suggested idea that someone who wasn’t homicidal to start with might become so from watching a movie seems deeply silly to me. But I think they encourage a dark side of ourselves, a cruel side that delights in others’ pain.

If that’s what you’re watching horror movies for, something has gone wrong. Sure, the same could be said of watching crime dramas or the initial rounds of The X Factor, but this is where, I believe, the danger of the horror genre really lies.

Horror movies are like rollercoasters. Scary, fun, dangerous if they’re made by unscrupulous people, and not for everyday use. Not everybody enjoys them, but not everybody has to. However, unlike rollercoasters, they can open the doors to deep spiritual discussions, and I, for one, will always be a fan. I just won’t watch them with my wife.