‘No’ says David Instone-Brewer

‘Superbabe!’ That was one of the newspaper headlines announcing the world’s first test-tube baby born in Manchester, 1978. The public reaction was one of excitement – though also considerable unease – about the ethics of in vitro fertilisation (IVF).Four years later, unease turned to horror following a casual confession in a TV interview by Robert Edwards, one of the IVF pioneers. Speaking about the experiments he was conducting, Edwards mentioned that ‘spare embryos can be very, very useful. They can teach us things about early human life’. Suddenly the public started asking questions: What exactly is an embryo? Are we experimenting on unborn babies and then throwing them away?

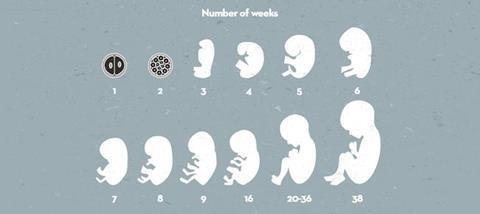

Formation of an individual

Mary Warnock was asked to form a committee with a majority of non-scientists that would represent a breadth of religious and moral views on IVF. Predictably, when the committee issued its report in 1984, it had reached a split opinion. Some felt that the UK would fall behind if its embryo research was limited in any way, while three members concluded that all such research should end immediately.

The two groups differed with regard to the key question: when does individual life begin? When does an embryo change from being a bundle of undifferentiated cells into a living human individual?

The Bible clearly refers to unborn children as living individuals. While in Elizabeth’s womb, John the Baptist ‘greeted’ the mother of Jesus (Luke 1:44), God told Jeremiah he had made plans for him before he was born (Jeremiah 1:5), and in the law of Moses, someone who accidentally killed a foetus was punished as a murderer (Exodus 21:22). Abortion debates have taken such verses as proof texts, but the issue is not so straightforward because in God’s eyes we are individuals long before conception. For example, God’s plans for Jeremiah were made before conception, because God said ‘before I formed you in the womb’ (Jeremiah 1:5, ESV). These verses tell us about God’s wonderful forward planning but they don’t tell us much about the status of a foetus.

When does a foetus have rights?

Although the Bible is not clear on the subject of when individual human life starts, most Christians decide that it is at conception. Catholic theologians pinpoint the act of coitus because this is where the ‘potential’ for life begins.

Half of the Warnock Committee agreed with the Christian viewpoint, while half felt that individual rights did not begin until a foetus could live independently outside the womb. It looked as if agreement was impossible, until a surprise suggestion was made, which the majority of the committee was able to accept. The consensus they came to was that individual life cannot begin before 14 days and that cell bundles younger than this had no individual rights. This seemingly arbitrary date is actually a clever and considered solution based on logic that speaks to both biologists and theologians.

Fourteen: the magic number

For biologists, 14 days marks the start of cell differentiation: before this, the embryo has no precursors of nerves or blood, so it cannot possibly know or experience anything. At about 14 days, a thin ‘primitive streak’ of cells appears that later becomes a tube extending through the body that will eventually differentiate into a mouth, stomach, intestines and anus. At about 21 days, a similar neural tube starts developing which will grow into the spinal cord with a bulge that will eventually become the brain. (This process reminds me of our homely translations of Psalm 139:13: ‘you knit me together in my mother’s womb’.)

So at day 14, the number of nerve and brain cells in the human embryo is zero, and it has less complexity than the simplest microscopic worm and less feeling or intelligence than a parasite in dirty drinking water. However, the argument is still far from clear-cut as, of course, these 14-day-old human cells have much greater potential than any worm or parasite. Should they, therefore, even at this stage, be regarded as an individual?

Turn to twins

For a completely different reason, theologians might also regard 14 days as a significant starting point for individual life. This is the date before which the cell-bundle could split into identical twins or larger multiples. We don’t know if God injects a fully formed spirit at some point (like Plato imagined) or whether our spirit develops while our body develops. However, we can be sure that God does not give an individual spirit to a bundle of cells before 14 days because if those cells did subsequently split into identical twins, they would have only half of a human spirit each. Theologically speaking, therefore, individual spiritual life cannot start before 14 days after conception.

I find this argument convincing. Others disagree. Pope John Paul II spoke for many Christians when he wrote, ‘From the time that the ovum is fertilised, a life is begun which is neither that of the father or the mother; it is rather that of a new human being with his [or her] own growth’.

It is, of course, simpler to say that individual life begins at conception, but this is problematic because a single cell cannot be said to be a human. If we say such cells have the potential of becoming human life, then Catholics are right to argue that the unjoined sperm and egg also have a similar potential for life, and anything that stops them joining (such as a condom or withdrawal) is morally equivalent to abortion. But if this is the case, surely the same can be said about a refusal to have sex – or perhaps even a refusal to marry! – as these are also decisions that prevent the sperm meeting the egg.

No abortion after day 14

A law forbidding all abortion after 14 days would have potential support from embryologists and ethicists, so it would be a solid basis for presenting to legislators. Rape victims could be helped by being able to take the morning-after pill, which acts long before the start of individual life. It would be illegal to decide to abort babies with congenital abnormalities because they would be regarded as human individuals equally before birth and after birth. Abortions could only be performed when the mother’s life was in danger.

A biologically ethical, theologically sound and legally workable argument for banning abortion – and a way of condoning contraception? It’s called the 14-day rule.

David Instone Brewer is senior research fellow in Rabbinics and New Testament at Tyndale House, Cambridge

‘Yes’ says Peter D Williams

I was saddened and also taken aback by Dr. David Instone-Brewer’s article arguing for a re-framing of the Christian position on abortion.

The conclusions he comes to are as dangerous as they are fallacious. If accepted, they risk compromising the vital public, ecumenical, and prophetic witness of Christians to the dignity and rights of unborn children.

A matter of life and death

Abortion is one of the most controversial issues in our culture, because it is, quite literally, a matter of life and death. Hence, we have thought about it in light of the gravest (in human terms) of the Ten Commandments: ‘You shall not murder’ (Exodus 20:13; Deuteronomy 5:17).

As Christians, we believe that human beings are made in the image of God, and therefore have an inherent moral value, or ‘dignity’, which forms the foundation of all our rights. If the unborn child is a living human being, then abortion is nothing less than the killing of an innocent life. If, however, the unborn child is just a collection of matter, essentially indistinguishable from a woman’s appendix, then abortion is more ethically akin to birth control, if not simply a matter of moral indifference.

Helpfully then, Instone-Brewer correctly characterises the central issue of controversy. Not, as is it is commonly put, ‘when does life begin?’ (‘Life’ is an unhelpfully broad term and concept), but ‘when does an individual life begin’?

In his article, Instone-Brewer ridiculously caricatures the Catholic theological answer to this question, erroneously describing it as having to do with the act of sex itself, and even as making a moral equivalence between abortion and artificial contraception. Suffice it to say, this is all absurd nonsense. The truth is that, whilst the Catholic Church has condemned abortion for her entire history, since the 19th century particularly (when embryological science became sophisticated enough for us to discern precisely what is going on in the womb) she has maintained that the crucial start of individual existence is conception. In fact, this has been the teaching of Christians from all theological traditions, and not because, as Instone-Brewer suggests, this is ‘simpler’, but because it is an indisputable scientific fact.

We see this confessed in medical and biological textbooks used in universities today. The first page of Larsen’s Human Embryology states that, ‘... [W]e begin our description of the developing human with the formation and differentiation of the male and female sex cells or gametes [sperm and egg], which will unite at fertilisation to initiate the embryonic development of a new individual’.

There is a term for the form taken by this new developing human individual: ‘zygote’. As O’Rahilly & Müller put it in Human Embryology & Teratology: ‘Zygote: This cell results from the union of an oocyte [egg] and a sperm. A zygote is the beginning of a new human being (i.e., an embryo)’. Moore and Persaud in their book The Developing Human, describe this as ‘[t]he initial totipotent cell that is the result of fertilisation marked the beginning of each of us as a unique individual’.

What does it mean to be human?

What science inescapably tells us then, is that each of us as a unique individual human being began when the sperm of our father and the egg of our mother united in what we call the ‘conception’ of a new person.

Instone-Brewer’s own narrowing of the question of individual life (’… when does an embryo change from being a bundle of undifferentiated cells into a living human individual?’) is thus fundamentally mistaken. The embryo, as a ‘bunch of undifferentiated cells’ is a living human individual. Only by unscientifically redefining what it means to be a human being can you avoid this reality.

Despite all this, Instone-Brewer expresses his preference for the findings of the 1984 Warnock Report, which recognised the embryonic human being’s moral status only after 14 days. His reasons, derived from the Warnock Commission itself, are two-fold. Firstly, that ‘the embryo has no precursors of nerves or blood, so it cannot possibly know or experience anything’ so it has ‘less complexity than the simplest microscopic worm and less feeling or intelligence than a parasite in dirty drinking water’. Secondly, that ‘we can be sure that God does not give an individual spirit to a bundle of cells before 14 days because if those cells did subsequently split into identical twins, they would have only half of a human spirit each. Theologically speaking, therefore, individual spiritual life cannot start before 14 days after conception’.

The problem with the first reason is that it begs the question, and is just as true of human beings after 14 days as before it. Is knowing and experiencing things what makes us human individuals? Why? And if so, surely similar denials of personhood could be applied to unborn children who are not yet ‘sentient’, the severely mentally disabled, people in comas or persistent vegetative states, and indeed anyone in a very deep sleep.

The Soul

As for the second reason, a rational account of twinning and the soul can be made without abandoning the idea that a ‘spiritual’ individual begins at conception. As David Albert Jones proposes in The Soul Of The Embryo, it could simply be said that the human embryo has abilities that are lost later in life. Just as when a starfish (as with various other species) generates a new individual from its separated parts when divided, so can an unborn child prior to 14 days. This may be ‘weird’ to us, but since God gives a new soul to the bodies of new human individuals that are created, so a new soul can be said to be given when a second embryo is created by the ‘splitting’ of a zygote.

That conception is the beginning of the human being is the central fact that should inform our ethic on abortion. To move this understanding to 14 days later would be an unreasoned injustice, and though it might be rhetorically convenient (e.g. for ‘hard cases’ such as rape) it would not realistically be any more acceptable to our political consensus.

The witness of Christians on countless injustices such as slavery, child labour, and the denial of civil rights, has been an important element of our shared history and prophetic social vocation. Let us not let bad philosophy from secular thought undermine what is an undoubtedly countercultural, but morally vital, part of our mission to build the Kingdom of God. Instead, let us affirm and fight for the humanity and dignity of everyone, especially the most vulnerable members of the human family.

Peter D. Williams is executive officer for Right To Life, and a Catholic writer and commentator