Determined ninja-shoppers jumped queues, elbowed, shoved and even punched each other in their determined pursuit of alleged bargains. The spirit of Ebenezer Scrooge, the lead character in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, was alive and well.

We don’t have to wrestle with fellow shoppers to qualify as cheap. We’ve all been around people who are the last in line when it comes to paying. At the coffee shop, they open the door and insist that you go in first. This is not out of courtesy, but a tactical manoeuvre to ensure that you get to the counter before them and are more likely to flash your credit card. Or at the end of a pleasant meal, their sudden departure to the bathroom is timed precisely to coincide with the arrival of the bill at the table.

All of this manipulative meanness not only takes a lot of effort, but actually robs us of the joy of giving. A recent sociological survey featured in The Paradox of Generosity (a book written by Christian Smith and Hilary Davidson; OUP USA) revealed that generosity is very good for us, and not in a televangelist ‘give and God will make you rich’ way. The research revealed that the more generous we are the more happiness, health and purpose we enjoy in life. Generosity not only blesses others; it also warms our own hearts.

More importantly, generosity changes the world. The early Christians profoundly impacted their culture through their generous lifestyles, even though most of them were poor. In their day, generosity was not widely valued as Roman society embraced a system called ‘Liberates’. Simply put, the code went like this: you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours. This was a tidy arrangement, unless you were poor and had nothing to give. Widows and orphans found themselves stranded at the bottom of the social food chain.

In beautiful contrast, the early followers of Jesus gave their service, money, goods, time, safety, creature comforts and reputations with a generosity that was not just a series of isolated, unusual actions, but a way of life. They looked for sweaty feet to wash and when terrible plagues hit and huge swathes of the population fled the cities, abandoning the sick, the Christians stayed behind, nursing the ill back to life, with some of the carers dying as a result.

It has been said that we are most like God when we give. Those early believers didn’t just share words and ideas about God; they showed a confused world what the giving God looks like.

So this year, let’s choose to live generously. Give that stretch of tarmac to the bullish driver who rudely cuts in during the rush hour. Offer the rare gift of listening. Instead of fuming over the man who stands in the ‘five items only’ queue in the supermarket with eight items in his basket, smile and wish him a pleasant day.

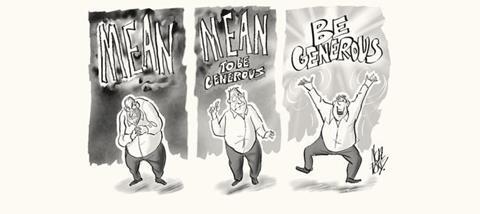

Too many of us practise post-dated generosity: one day we’ll get around to giving, but we mistakenly think that, until we do, believing in the idea is enough. It isn’t. And if we’re honest enough to admit a tendency to be tight, we can change.

He’s obviously a fictional character, but Scrooge changed. Dickens describes the transformation: ‘Many laughed to see this alteration in him, but he let them laugh and little heeded them…his own heart laughed and that was quite enough for him.’